The voyage to the spirituality of the Sacred Heart for our province necessarily leads us to Rome. It is here that Brother Maurice charted and life-tested the map which we have taken as our guide. Here he consecrated eighteen years in the prime of his life to making his own intense personal response to God’s ineffable gifts and intimate presence. Ineffable is his word.

Well before his three six-year terms as vicar and then superior general,[1] he spent 1952-53 in Rome in a sabbatical year for personal formation.[2] He set as his goal to deepen in himself the spirituality of the Sacred Heart. Taking advantage of being at the general house to mine the archives, he read every circular letter about the Sacred Heart written by superiors general from Andre Coindre (1825) through Brother Albertinus (1948) so he could be inspired by how they lived our patronal spirituality.

What arose from his personal research was a pressing desire to make a decisive act of consecration to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, “body, soul, and life … in a solemn way.”[3] He came to place special stress on the word consecration, which he likened to a ship’s keel that gives direction and depth to the vessel. A self-defining act of consecration would be his response. With the support of Brother Alvarez (Huard), the spiritual director of the sabbatical program, he made a formal act of consecration in the hope that this heartfelt gesture would be a “personal embrace of Jesus’ divine and human love” for him. He also discovered in himself a desire to lead others to consecrate themselves. The opportunity to act on that desire on a worldwide scale came with his call to return to Rome in 1964 to serve on, and eventually to lead, the general council.

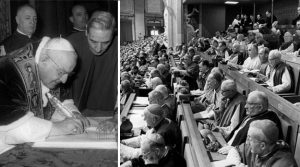

Brother Maurice, chosen as spiritual leader first by his brothers in Canada and then by the whole institute, saw it as his responsibility to be a prophetic voice calling for conversion in our approach to devotion to the Sacred Heart. The teachings of Vatican Council II (lines 9-10), his source of spiritual food even while they were in draft form, confirmed and amplified interior convictions that grew from his experience. In the Rome archives we find letters he wrote even before the Council, while he was provincial in Canada, articulating the need for conversion. He spoke for his brothers in asserting that the multiplication of devotions, acts of piety, and recited prayers risked becoming empty formulas irrelevant to their apostolic mission.

“Because we belong to an apostolic community, our duty of state is to kindle directly in others the fire of the love of God so that they do not die from the cold. This means that the prayer schedule needs to be changed in such a way as to facilitate the apostolic works and to prevent excessive fatigue.”[4]

Vatican Council II

A misunderstanding Brother Maurice hoped to eliminate from our spirituality was the dualistic tendency to put prayer in one compartment of our lives and our ministry in a completely separate one: “The love of Christ should pass through our human love in such a way that the two become one.”[5]

His hopes were confirmed by the teaching of the Second Vatican Council in its decree Growth in Love about unifying prayer and work:

“The members of every community, seeking God solely and before everything else, should join contemplation, by which they fix their minds and hearts on Him, with apostolic love, by which they strive to be associated with the work of redemption and to spread the kingdom of God.”[6]

In the context of what was being taught about spirituality in religious life and in the Church before the Council, both of those citations make an extraordinary – and fully intended – omission. It’s worth re-reading them carefully. Note that they say nothing about the benefits of prayer for ourselves. We are not the object of contemplation nor of petition. Nor are we seeking reward. Instead, they re-affirm our self-emptying even as we pray, calling us to contemplate God’s love and the needs of others, then to find ways to serve as a channel of reconciliation between both.

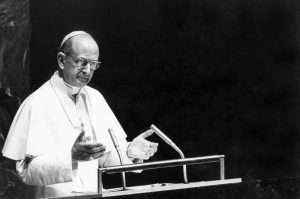

Pope John XXIII deliberately chose to announce the Vatican Council on the Feast of the Conversion of Paul in 1958 to underline that the whole Council would be a call to conversion.

The Spirituality of the Mirror

Exactly what was it about spirituality during the1960’s that made the teaching of the Church and Brother Maurice a call to conversion?

The promotion in the Church of devotion to the Sacred Heart over time relied on the offer of indulgences as incentives or rewards for those who recited certain prescribed prayers. For example, the twelfth promise linked to Saint Margaret Mary assures a place in heaven for those who go to communion on nine consecutive First Fridays. The proliferation of such indulgences in the Church produced a culture of earning grace to secure good real estate behind the pearly gates.

Among the brothers, this merit-based approach to spiritual practices

became institutionalized. For example, Annuaire articles over the years published opportunities for earning indulgences; one issue devotes nine pages to cataloguing a wide range of indulgence categories (plenary, partial, attached to prayers …) while specifying cases for which special religious articles had to be held by the one seeking the indulgence.[7] The brothers’ Constitutions and Rules in vigor in 1964 at the start of Brother Maurice’s service in Rome says the purpose of the institute is to be “a common discipline … to attain eternal happiness” and “a means of [the brothers’] laboring for their own sanctification.” Grace had to be earned. Mass attendance had to be enforced by the pain of sin. Acts of penance were prescribed.

What had evolved over time was what might be called a spirituality of the mirror, before which we do good works and adopt religious practices which reflect back on us. We work to make ourselves holy. So that we can assure our progress in personal holiness, we look at ourselves in the mirror that is the Rule to compare ourselves to the ideals and virtues it holds us to. We follow the rules to be perfect. We use the mirror to brush our hair and to check our appearance. We build up spiritual assets in the form good works that God can’t overlook when it comes time for God to look us over at our final judgment.

In the decades before the Council, the Church called religious life “the state of perfection.” The approved rule was our official way to perfection. Such a self-absorbed spirituality betrays anxiety about our salvation; at its root lies a lack of trust in God’s too-good-to-be-true promise of love, holiness, forgiveness, and eternal life.

Call to Conversion

The call to conversion by Vatican II was a call to give up our spirituality based on meriting salvation. The Council wanted us to abandon self-serving motives and eliminate any consideration of what we get for ourselves through our piety. Light to the Nations,[8] the dogmatic constitution on the Church, was promulgated during the first month of Brother Maurice’s service of leadership in Rome. It is there that the Church’s challenge for us to abandon all forms of self-serving spirituality is most emphatic:

“The followers of Christ are called by God, not because of their works, but according to His own purpose and grace. They are justified in the Lord Jesus, because in the baptism of faith they truly become [children] of God and sharers in the divine nature. In this way they are really made holy. Then too, by God’s gift, they must hold on to and complete in their lives this holiness they have received.” (40)

The sound you can imagine is that of a mirror shattering,  and with it the Rule and the commands that absolutized it. The Church withdrew its sponsorship of the imperatives “Save your soul.” and “Make yourselves holy.” It abolished the pedagogy of guilt and the system of rewards and punishments.

and with it the Rule and the commands that absolutized it. The Church withdrew its sponsorship of the imperatives “Save your soul.” and “Make yourselves holy.” It abolished the pedagogy of guilt and the system of rewards and punishments.

Another sound arises; it is the mourning of generations of Catholics, among them brothers, who grew up following the spiritual map which, after incentivizing us through fear, merit, and indulgences, was jettisoned along with Latin and fish on Fridays. The conversion from a merit system was not easy. The sound of the mourners was a wail of resentment for being told they’ve been waiting all their life in the wrong line. Brother Maurice and their provincials worked at listening and helping them as they unfolded and tried to follow the new map which the Church and the institute collaborated in charting, but which no longer corresponded to the prayer books and retreat notes that inspired them over the years leading up to 1964.

Liberation

There is a third sound: shouts of liberation from those, among them Brother Maurice, who had been waiting a long time to enjoy “the sublime and unending and glorious freedom of the [children] of God” (Rom. 8:21) proclaimed by Pope Paul VI.[9]

Fifty years after Light to the Nations changed forever the fundamental principles of the Church’s teaching on spirituality, the Catholic Theological Society of America published its synthesis of Vatican II’s call to spiritual conversion:

“God is always drawing us to deeper and deeper intimacy, away from a self-absorbed life to a Godward-directed life and to a way of living that embraces self-giving love—‘Love God with all your heart’; ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’”[10]

Once again, our ego is not in the picture. The Church asks us to pray for conversion to a spirituality purified of me-anxiety enforced by a system of rewards and promises.

Pope John’s Window

The Church fortunately didn’t just leave us there with shards of mirror around our feet on its marble floor. It exchanged the mirror for a window whose panes are clear glass—other-centered glass, if you will.  On the day Pope John XXIII convoked the council, he said,

On the day Pope John XXIII convoked the council, he said,

“I want to throw open the windows of the Church so that we can see out and the people can see in.”

That desire and that image struck a deep chord. More than all the long theological documents with Latin names, the image of Pope John’s window has become an emblem of the Church’s conversion.

The two-way window signifies the Church’s new paradigm of spirituality for today’s world. In presenting a window, John intentionally didn’t propose the one-way stained glass window of a cathedral, even though for centuries such wonders of sacred art have been objects of contemplation and of spiritual uplift. Think of the jewel in the heart of Paris that is La Sainte-Chapelle, whose 360 degrees of intricate arched windows transport millions of visitors each year into a wondrous otherworldly consciousness.

John was referring to ordinary windows like the often-shuttered ones in the papal apartments. He wanted the Church to look through transparent glass, the better to contemplate the ordinary people around us. Instead of saintly figures in crystal mosaics, Pope John holds up for prayerful veneration by churchmen, popes and us the beauty, the color and the light of divine possibilities imbuing the hearts of our contemporaries.

Our spirituality places us at the open window where we fix our eyes, ears, and heart on contemplating

“the joys and the hopes, the griefs, and the anxieties of the people of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted. Theirs are also our joys and hopes, griefs and anxieties. Indeed, nothing genuinely human fails to raise an echo in our hearts. For ours is a community of ordinary human beings. United in Christ, the Holy Spirit leads us on our journey to the Kingdom of our Father and we have welcomed the news of salvation—which is meant for everyone. That is why the community that is the Church realizes that it is truly linked with humanity and its history by the deepest of bonds.”[11]

Thanks to the leadership of Brother Maurice, our spirituality has been converted by a prolonged compassionate gaze through the window given to us by the “Good Pope,” as the Italians liked to call him.[12]

Maurice took his light from the window of Vatican II as he promoted years of dialogue throughout the Institute leading to a complete rewriting of the Rule of Life during the 1970’s and 1980’s. John’s call to conversion in the Church gave our 55 year-old superior general relentless desire and energy to adopt the fundamental principles of the spirituality of the window. Through the Council, Maurice heard Jesus saying, “Lift up your eyes and see the people, the poor, those thirsting for justice. Here is my heart; from it draw the living water they are searching for.”[13]

A new distinctive sign

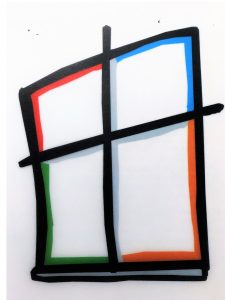

After the Vatican Council, many brothers, looking for a distinctive sign inspired by the revised Rule of Life that would express our communal conversion, began wearing a metal cross with an open heart at its center designed by Brother Anicet Paulin of the District of Australia.

That cross quickly spread through Canada and the wider institute as an emblem of the new rule’s point of reference for our spirituality: the open heart of Jesus on the cross as witnessed by the beloved disciples. Later, in the U.S., Brother Anicet’s cross was slightly modified, but its significance remained unchanged: the open heart of Jesus is the window through which we look out upon our contemporaries and the realities they face.

The General Chapter of 2000 gathered fifty-three brothers from thirty-three countries in Rome to join the Church in celebrating the year of the Great Jubilee, the 2000th anniversary of the Sacred Heart event. To start the Holy Year, French Cardinal Roger Etchegaray[14] evoked the pierced heart of Jesus at the ceremony of opening of the Jubilee door at St. Peter’s basilica. Inspired by that ceremony, our general chapter’s preparation team commissioned a logo to set the theme for the millennial chapter. The logo widens the open heart of our distinctive cross into the window of Vatican II.[15] The cross remains, but the outline of the heart expands to form a window of four panes. In our spirituality of the window we want to gaze upon everyone around us through the open heart of Jesus on the cross. And we want them to see our heart as a window, not a mirror.

The General Chapter of 2000 gathered fifty-three brothers from thirty-three countries in Rome to join the Church in celebrating the year of the Great Jubilee, the 2000th anniversary of the Sacred Heart event. To start the Holy Year, French Cardinal Roger Etchegaray[14] evoked the pierced heart of Jesus at the ceremony of opening of the Jubilee door at St. Peter’s basilica. Inspired by that ceremony, our general chapter’s preparation team commissioned a logo to set the theme for the millennial chapter. The logo widens the open heart of our distinctive cross into the window of Vatican II.[15] The cross remains, but the outline of the heart expands to form a window of four panes. In our spirituality of the window we want to gaze upon everyone around us through the open heart of Jesus on the cross. And we want them to see our heart as a window, not a mirror.

Contemplating through the window

This window was the vantage point through which the delegates to the Chapter of 2000 contemplated ways to respond to the needs of hope-deprived and poor youth at the threshold of the new millennium. Today the same window can help us undertake four prolonged contemplations indispensable to our spirituality. We can call them “cardinal contemplations” because they are essential. Cardinal comes from the Latin word for hinge, like those on the shutters and casement windows that Pope John threw open. Our spirituality hinges on four life-long, often-repeated, and life-giving contemplations through Pope John’s open window.

Before resuming our contemplative voyage, let us consider what contemplation means in our spirituality of the window.

Two Movements

When we pass an open window, we have a spontaneous reflex to look out to take in the view. In the practice of our spirituality, we convert that reflex into intentional contemplation of others through the eyes and heart of Jesus. Pope John and Brother Maurice show us through word and example that our contemplation unfolds in two movements:

- In the first, it begins as seeing, morphs into active regarding with all our senses, and becomes a purposeful gaze into the hearts of those before us.

- In the second movement, it opens into a prayerful discernment of how to respond with empathy and trust.

The first movement engages our heart and our mind; the second employs our will and our competence. The Rule of Life describes those two movements as first drawing from the stream of love tapped by the lance, then extending the stream to the young: “The spirituality of the Institute flows from contemplating Christ, whose open heart is a sign of the Trinitarian love of God for all. We respond in love.”[16]

Now we are ready to continue our voyage by travelling to four destinations where, with the open window of the heart of Jesus as our vantage point, we will undertake the four cardinal contemplations crucial to our spirituality. At each of four stops, we will complete both movements of contemplation:

First movement—gazing with the eyes of Jesus

— Look into hearts

— Feel his empathy

Second movement—responding in love with our own will

— Seek communion and solidarity

— Resolve to act

— Invest our gifts

The first movement without the second is pious spiritualism; the second without the first is pure humanism. We need both; each complements the other. The mutual interplay between the two movements is well expressed in a statement attributed to Meister Eckhart: “What we plant in the soil of contemplation we shall reap in the harvest of action.”

Rome:The Window

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

The Grace I Seek … the guidance of the Holy Spirit

I pray the prayer said at the start and end of every session of Vatican II:

We stand before you, Holy Spirit,

conscious of our sinfulness,

but aware that we are here in your name.

Come to us, remain with us, and enlighten our hearts.

Give us light and strength to know your will,

to make it our own, and to live it in our lives.

Guide us by your wisdom, support us by your power,

for you are God, sharing the glory of Father and Son.

You desire justice for all; enable us to uphold the rights of others;

do not allow us to be misled by ignorance or corrupted by fear or favor.

Unite us to yourself in the bond of love and keep us faithful to all that is true.

As we gather in your name, may we temper justice with

love, so that all our reflections may be pleasing to you, and earn the reward

promised to good and faithful servants.

The Grace of Vatican II

Vatican II 7 minute clip

Vatican II 23 minutes

Promotion of Laity in Church

Universal call to holiness

Reading the Signs of the Times Dianne Bergant America magazine November 24, 2003

One of the most exacting challenges from the Second Vatican Council was its summons to read the “signs of the times.” It was a call to reflect deeply on the events unfolding before our eyes and to respond to them out of mature faith. This was difficult, because many of us were accustomed to react to life rather than interact with it, and few of us possessed what today might be called mature faith. We probably knew the teachings of the church and were well grounded in genuine devotion, but we were passive rather than actively involved in critical thinking about faith.

This changed with the council. Over the years we have grown into social sensitivity. We take faith-based political stands. At times we even turn a critical eye to the teachings and traditions of the church. Our faith has matured and our devotion has been enriched by reading the signs of the times.

Today Jesus directs us: “When these signs begin to happen, stand erect and raise your heads, because your redemption is at hand.” Of which signs is he speaking? Is he really talking about the end of the world? Should we all start reading Carl Sagan or Stephen Hawking so that we know what to expect? Though such reading would certainly enrich our appreciation of the universe of which we are a part, Jesus is probably not talking about the cosmos. Then of what?

He clearly tells us. “Your redemption is at hand.” The days that Jeremiah said were coming are about to dawn, and we are called to read the signs of their dawning. The prophet described them as days of peace and fulfillment, of justice and security—a very encouraging picture. The Gospel paints a very different scene. It tells us that there will be suffering before these days really appear. And why will there be suffering? Because we, before the cosmos, have to be transformed.

Paul prays for our transformation. He prays that we will abound in love, that our hearts will be strengthened, that we will be blameless in holiness, that we will conduct ourselves to please God. The apocalyptic cosmic upheaval is a powerful metaphor to describe the cost of such transformation, especially for those of us who are so rooted in anger, fear, deception and “carousing and drunkenness and the anxieties of daily life.”

We know that the days of our redemption have already dawned with the coming of Jesus. But because our own transformation is always ongoing, we move yearly through the liturgical celebration of the mystery of our salvation. While Advent is set aside to commemorate Jesus’ coming in the flesh as well as his final coming in glory, it is also a time for us to open ourselves to the Lord’s coming into our lives and our world today. In order to do this, we must read the signs of the times.

One of the apocalyptic signs mentioned in the Gospel is the “dismay of nations.” This is certainly evident today, and unlike many times in the past, we are all personally affected by it. Some of us know people who lost their lives in acts of terror or war. Fear has made us suspicious of people of other races or religious beliefs. Sometimes our anger has grown into a desire for revenge, and our fear has taken on features of paranoia.

Some public officials have betrayed the trust we placed in them. They lied to us, misappropriated our money and led us astray. They seem too often to have placed their own personal advantage ahead of their responsibility to those who placed them in office. Our disapproval of their service has left many frustrated. Our inability to change the system has turned some away from any kind of civic involvement.

The sinfulness of our church, a sinfulness we have always acknowledged as a fact of human frailty, has been revealed in all its heinousness. The beauty of the body of Christ has been marred by scandal, slander of the innocent and disparagement of legitimate authority. Its shame is there for all to see.

If these are the signs of our times, how can we say that our redemption is at hand? Because these are not the only signs. In the face of all this dismay, we see heroism and patience and understanding; we see honesty and unselfish service of others; we see genuine holiness and fidelity. There are people in the world, in government, in the church, in our neighborhoods and in our families who are committed to justice and peace. Their lives testify that the reign of God has indeed taken hold. Advent reminds us that we too can be transformed into it, and so it calls to us all: “Stand erect and raise your heads, because your redemption is at hand.”

A Parable about Contemplating Philippe Cochinaux, O.P.

There was once an old man sitting at the entrance to a town called Haimran in the Middle East. A young man approached him and said to him: ‘I have never been here; what are the people of Haimran like?’ The old man answered him with a question: ‘What were the people in the town you came from like?’ ‘Self-centered and wicked. That’s exactly why I was so happy to leave,’ said the young man. The old man answered: ‘You will find the same people here.’

A little later, another young man approached him and put to him exactly the same question. ‘I have just arrived in this region; what are the people in Haimran like?’ The old man replied in the same way: ‘Tell me, my young friend, what were the people like in the town you just left?’ They were kind, welcoming, and trustworthy; I had good friends there; I was very sorry to leave,’ answered the young man. The old man replied, ‘You will find the same here.’

A merchant who was watering his camels not far from away had overheard the two conversations. As soon as the second young man went on his way, he protested to the old man: ‘How can you give two completely different replies to the same question put by two people?’ The old man replied, ‘Whoever opens his heart also changes his view of others. Everyone carries their universe in their heart.’”

We see what we see from the perspective of who we are. Above and beyond some of life’s realities that are quite complex and sometimes very painful, there are women and men whose life is a nagging complaint. Then there are those who go through life with a degree of gentleness. We are all affected by our respective stories. What is most important is to find on our journey people who take us by the hand and lift us up when we stumble. They are the visible sign of the presence of God at the heart of our humanness. They lead us to what we should contemplate, and above all, to how we might live differently. In fact, through our hearts, our view of the world can be transformed completely if we use Christian faith, hope and love as the eyes with which we advance on our journey as believers.

Contemplating with God’s eyes involves looking at the world with faith, in other words, always having trust in the other; recognizing that even if it happens that he becomes lost, he can recover and walk upright again on his life’s path. She can get a grip on herself and get back on track, find her bearings in order to walk. So we put trust in human beings despite their weaknesses.

Then again, living with God’s eyes means looking at the world with hope. Hope would leave our hearts forever if there were no signs to tell us that sometimes a person needs time to make unique discoveries and grow through failure and disappointment. …

Love enables us to respect the personal journey of each person, even to keep him company should he err and to rejoice when she returns to being herself. Love is always tinged with compassion, and so it enables us to live a life of forgiveness, or, better still, reconciliation. In this way, having the same faith, hope and love as Jesus enables us to look at the world differently, since each of us carries the universe in our heart. Amen

Action and Contemplation in The Joy of the Gospel

Pope Francis’ “Loving attentiveness to the poor” par. 199

Our commitment does not consist exclusively in activities or programs of promotion and assistance. What the Holy Spirit mobilizes is not an unruly activism, but above all an attentiveness which considers the other “in a certain sense as one with ourselves”.[166] This loving attentiveness is the beginning of a true concern for their person which inspires me effectively to seek their good. This entails appreciating the poor in their goodness, in their experience of life, in their culture, and in their ways of living the faith.

promotion and assistance. What the Holy Spirit mobilizes is not an unruly activism, but above all an attentiveness which considers the other “in a certain sense as one with ourselves”.[166] This loving attentiveness is the beginning of a true concern for their person which inspires me effectively to seek their good. This entails appreciating the poor in their goodness, in their experience of life, in their culture, and in their ways of living the faith.

True love is always contemplative, and permits us to serve the other not out of necessity or vanity, but rather because he or she is beautiful above and beyond mere appearances: “The love by which we find the other pleasing, leads us to offer him something freely”.[167] The poor person, when loved, “is esteemed as of great value”,[168] and this is what makes the authentic option for the poor differ from any other ideology, from any attempt to exploit the poor for one’s own personal or political interest. Only on the basis of this real and sincere closeness can we properly accompany the poor on their path of liberation. Only this will ensure that “in every Christian community the poor feel at home. Would not this approach be the greatest and most effective presentation of the good news of the kingdom?”[169]

Without the preferential option for the poor, “the proclamation of the Gospel, which is itself the prime form of charity, risks being misunderstood or submerged by the ocean of words which daily engulfs us in today’s society of mass communications”.[170]

Since this Exhortation is addressed to members of the Catholic Church, I want to say, with regret, that the worst discrimination which the poor suffer is the lack of spiritual care. The great majority of the poor have a special openness to the faith; they need God and we must not fail to offer them his friendship, his blessing, his word, the celebration of the sacraments and a journey of growth and maturity in the faith. Our preferential option for the poor must mainly translate into a privileged and preferential religious care. [200]

Footnotes

[1] Brother Maurice was elected Vicar (First Assistant) to Brother Jules Ledoux in 1964, Superior General in 1970 and again in 1976. His term ended in 1982 when Brother Jean-Charles Daigneault succeeded him.

[2] The Grand Novitiate was a 9-month international spiritual renewal program for perpetually professed brothers.

[3] Brother Maurice (Paul-Hervé), “The Sacred Heart of Jesus,” personal paper (July 1, 1952), 14-16, Rome, Archives of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart

[4] Archives A11.059 June 1963 (while Vatican II was in process)

[5] We are Present to Them, par. 49

[6] Perfectae Caritatis, 5

[7] Annuaire 33-056

[8] Lumen Gentium, November 1964

[9] Declaration on Religious Freedom, Vatican Council II, 1965

May the God and Father of all grant that the human family, through careful observance of the principle of religious freedom in society, be brought by the grace of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit to the sublime and unending and “glorious freedom of the sons of God” (Rom. 8:21).

[10] Ormand Rush, “Ecclesial conversion after Vatican II” (Catholic Theological Society of America: Proceedings of 2013) file:///C:/Users/bgcouvillion/Downloads/4738-9854-1-PB.pdf

[11] Constitution of the Church in the Modern World (1965), paragraph 1, edited for inclusive language.

[12] http://usccbmedia.blogspot.com/2014/04/pope-john-xxiiis-gift-to-church-laity.html

[13] We are Present to Them, 8

[14] https://cruxnow.com/global-church/2017/01/26/cardinal-etchegarays-retirement-means-end-era/

[15] General Chapter of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart (Rome, January 2001) Lord, when did we see you? p. 4

[16] Article 14; see also line 7 of the map