The Croix Rousse: Pieux-Secours [lines 12-14]

Wounded Youth

The journey to the fourth cardinal contemplation from our window takes us back in time to Lyons in 1818. From the Saône River we climb the switchbacks of a pedestrian passageway to arrive at the Croix Rousse quarter.

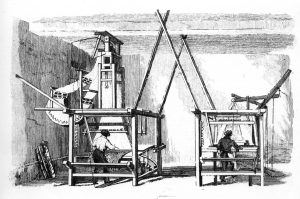

We reach a solid rampart anchored to Fort St-Jean, which once protected an extensive Carthusian monastery. Its former land has been sectioned off into privately owned parcels of businesses and estates. The corner parcel nearest the fort is our destination. Andre Coindre has made a three story building there the keystone of his vision for the boy prisoners of l’Antiquaille. He bought it with his father from a silk merchant because of the possibilities offered by its seven room-sized industrial looms ideally equipped for boys to apprentice in Lyons’ silk industry.

We reach a solid rampart anchored to Fort St-Jean, which once protected an extensive Carthusian monastery. Its former land has been sectioned off into privately owned parcels of businesses and estates. The corner parcel nearest the fort is our destination. Andre Coindre has made a three story building there the keystone of his vision for the boy prisoners of l’Antiquaille. He bought it with his father from a silk merchant because of the possibilities offered by its seven room-sized industrial looms ideally equipped for boys to apprentice in Lyons’ silk industry.

To understand a Jacquard loom, click this link:

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/videos/j/video-jacquard-weaving/

A Place of Sanctuary

The final line of Brother Maurice’s map speaks of our vision of “building the earthly city so that it will be founded on and renewed in Christ.” We are here to contemplate our very first establishment inspired by that vision of an earthly city rebuilt on Christ, which the general chapter of 2006 called “the sanctuary of our mission.”

Andre named this innovative sanctuary Pieux-Secours, which translates as Godly-aid. The awkwardness of the hyphenated name takes nothing away from its genius. The name is perfect short hand to describe our spirituality of two components. The first word, an adjective, describes us, bonded to God. The second, a noun, is our response. We, saved, reach out to save. We, grateful, pay our gifts forward. We, faith-filled, do works. Andre wanted Godly-aid to be a permanent human institution whose name professes its divine origin so that the boys living there might know that God sends help, not just lovely sentiments, in the form of compassionate and competent adults.

We linger at Pieux-Secours to look through its rows of tall windows at the boys inside at serious work on sophisticated looms[1] alive with noisy hope. Andre describes the young weavers to the civic community and its leaders, from whom he is seeking funding pledges and moral support:

“Some are children who have in the past given their parents serious cause for concern due to their intransigence or the gravity of their offenses. Some of them, free-spirited and independent, are reluctant to give themselves over to any sedentary occupations; they often wander on the docks and public squares, a prey to all the evils of vagrancy and to the wiles of unsavory characters. Others have recently been victims of the behaviors from which it is our aim to shelter them. They were young prisoners who, having been incarcerated for a more or less lengthy period, find that no one will give them work. However, they are deserving of the special concern and of individual attention which has for some time been exercised on their behalf in an effort to set them on the path of goodness. Guilty at an age when boys tend to be reckless rather than wicked, impetuous rather than incorrigible, hope for their transformation must never be lost. They must be surrounded with every possible help in order to form them to good habits; they must be isolated … from exposure to criminal contagion from the inmates.”

Youths with ‘noble hopes’

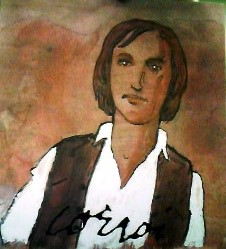

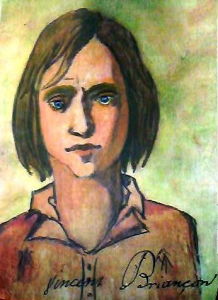

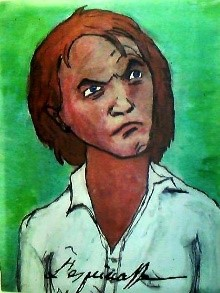

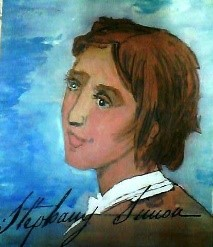

Researchers at Andre Coindre International Center[2] have discovered the names and stories of some of the young people, all teenagers, whom Andre knew personally. We contemplate them with the help of an artist’s rendering[3] and a thumbnail sketch drawn from Lyons’ municipal archives.

Jean Corroi was twelve when his father, a lumberjack, died and his mother, a washerwoman with no means, brought him to Father Coindre so he could be enrolled in the Pieux Secours. In place of usual primary school classes, John and several companions his age learn reading, writing, calculating, and religion while learning how to operate looms. He works several hours a day weaving cloth to be sold. The money from his work is saved in an account held for him until he finishes his 8-year program at the age of twenty. In this way he would have both a skill and a bank account at the time of his graduation. John died of an unknown illness before he completed his contract. We don’t have his signature because neither he nor his mother could write when the apprenticeship contract began. The name written over the drawing comes from a list of names in the founder’s handwritten notes.

Jean Corroi was twelve when his father, a lumberjack, died and his mother, a washerwoman with no means, brought him to Father Coindre so he could be enrolled in the Pieux Secours. In place of usual primary school classes, John and several companions his age learn reading, writing, calculating, and religion while learning how to operate looms. He works several hours a day weaving cloth to be sold. The money from his work is saved in an account held for him until he finishes his 8-year program at the age of twenty. In this way he would have both a skill and a bank account at the time of his graduation. John died of an unknown illness before he completed his contract. We don’t have his signature because neither he nor his mother could write when the apprenticeship contract began. The name written over the drawing comes from a list of names in the founder’s handwritten notes.

Vincent Briançon was thirteen when he met Father Coindre. In his town, Annecy, there was strong Catholic-Protestant animosity. His father, a stout Protestant, who operated a hardware store, threatened and beat Vincent because he wanted abandon his father’s faith to join the Catholic side of the family. But Vincent was strong-minded. To escape the violence at home he ran away to stay with his Catholic relatives. When his father came looking for him, they hid him for four hours in a closet of the church sacristy. Eventually they disguised him as a girl, spirited him out of town, then passed him to other relatives until he made his way to Lyons, where a priest gave him clothes and brought him to Pieux–Secours, where he encountered about twenty other boys. Eventually the police tracked Vincent there and brought him back to his family. His signature comes from a police form.

Vincent Briançon was thirteen when he met Father Coindre. In his town, Annecy, there was strong Catholic-Protestant animosity. His father, a stout Protestant, who operated a hardware store, threatened and beat Vincent because he wanted abandon his father’s faith to join the Catholic side of the family. But Vincent was strong-minded. To escape the violence at home he ran away to stay with his Catholic relatives. When his father came looking for him, they hid him for four hours in a closet of the church sacristy. Eventually they disguised him as a girl, spirited him out of town, then passed him to other relatives until he made his way to Lyons, where a priest gave him clothes and brought him to Pieux–Secours, where he encountered about twenty other boys. Eventually the police tracked Vincent there and brought him back to his family. His signature comes from a police form.

Lespinasse We only have his last name. Father Coindre writes of him often in his letters; once he complained that Lespinasse liked to pry into everybody’s affairs to ferret out news to spread. The name on the drawing is in the founder’s handwriting. Lespinasse, about seventeen years old, is one of the older boys whom Andre succeeded in rescuing from prison. He became so successful that he taught other boys and even new recruits to the brotherhood how to work the complex Jacquard looms, state-of-the-art industrial technology in 1818. As his incarceration would indicate, he resists discipline; one night he slipped out of the dormitory and was on the verge of being expelled, but Father Coindre persuaded the Brothers to keep him, correct him, and bring him around. Records suggest that Lespinasse eventually was transferred to another one of the Brothers’ schools.

Lespinasse We only have his last name. Father Coindre writes of him often in his letters; once he complained that Lespinasse liked to pry into everybody’s affairs to ferret out news to spread. The name on the drawing is in the founder’s handwriting. Lespinasse, about seventeen years old, is one of the older boys whom Andre succeeded in rescuing from prison. He became so successful that he taught other boys and even new recruits to the brotherhood how to work the complex Jacquard looms, state-of-the-art industrial technology in 1818. As his incarceration would indicate, he resists discipline; one night he slipped out of the dormitory and was on the verge of being expelled, but Father Coindre persuaded the Brothers to keep him, correct him, and bring him around. Records suggest that Lespinasse eventually was transferred to another one of the Brothers’ schools.

Stephanie Simon was the youngest of four sisters. Both parents died when she was an infant; Father Coindre got to know the girls when he was assistant pastor of their parish. Her legal guardian, an uncle, neglected her, so her oldest sister took charge of her, but Stephanie did not want school. By the time she was fourteen she had been to five different ones. Nothing was working out, so she writes to Father Coindre for help. The signature we have comes from a letter to him in which she tells him a lie. She is trying to manipulate him so she can drop out of school and get a job as an apprentice. Two of her sisters, both nuns, become very upset when their eldest sister gave in to “Fannie” by letting her live behind a dress shop, where she would be unsupervised. They fear the moral danger she is likely to succumb to. Father Coindre sends a young woman who ran a florist shop to take her in and give her supervision and work.

Stephanie Simon was the youngest of four sisters. Both parents died when she was an infant; Father Coindre got to know the girls when he was assistant pastor of their parish. Her legal guardian, an uncle, neglected her, so her oldest sister took charge of her, but Stephanie did not want school. By the time she was fourteen she had been to five different ones. Nothing was working out, so she writes to Father Coindre for help. The signature we have comes from a letter to him in which she tells him a lie. She is trying to manipulate him so she can drop out of school and get a job as an apprentice. Two of her sisters, both nuns, become very upset when their eldest sister gave in to “Fannie” by letting her live behind a dress shop, where she would be unsupervised. They fear the moral danger she is likely to succumb to. Father Coindre sends a young woman who ran a florist shop to take her in and give her supervision and work.

As we contemplate them, we ask for the grace to see these teenagers as Andre—and God—did. Rather than dwell on their sneaky, insubordinate, and ambiguous behaviors or their illiteracy and immaturity, he saw their possibilities, which he called their “noble hopes.” By working closely with them, he discovered that the best approach is to avoid taking their manipulations personally and instead to contemplate their wounds. By doing so, he learned that their endurance of loss and suffering was a gauge of their deeper worth.

Wounded

Our spirituality begins with the contemplation of Jesus’ wounds. Andre’s example shows that it doesn’t rest there. Jesus is telling us the same thing he told the wailing women of Jerusalem: “Stop crying for me. Save your tears for your children.”[4] For us as educators, contemplating the wounds and sufferings of Jesus inevitably turns our contemplative gaze from him to the pains and cries inside the hearts of young people: Of those spiritually and materially rejected. Of those with parents distant due to death or indifference. Of those running away from violence. Of those pierced by tattoo needles and crucified by syringes. Of youth for whom Christian images are superficial emblems like brand names rather than icons of deep interior realities.

One remarkable thing about Jesus is that he invariably turns the crowds’ attention away from himself to those who are suffering. On almost every occasion when a sick person is brought to him, he ends the healing encounter by telling him or her, “Your faith has saved you.”[5] He takes no credit, instead turning the onlookers’ gaze away from himself to the suffering person. It’s so characteristic of Jesus that it became what seemed to be an automatic reflex.

There was a recent story in a week-long cable news cycle of an attacker in a train in Portland, Oregon, who, taken by xenophobic fury prompted by comments from the president, mauled two girls, an African-American and a Muslim, in a brutal stabbing. Micah Fletcher, 21, an onlooker, jumped in to stave off the madman, only to be stabbed grievously himself. The media made him into a coast-to-coast superhero. After being a guest in interview after news interview, he had enough and finally scolded the media, telling them to turn their cameras away from him to concentrate on the girls who were the “real victims.”[6] Fletcher called on viewers to an act of contemplation and empathy: “Imagine yourself being one of those girls.” Whether or not he was Christian, he did as Jesus wants us to do: focus our regard away from him and look through his eyes upon the victimized young. Andre Coindre once told Brother Borgia, who wanted time for more contemplative prayer, “Sometimes we must “leave God for God.”[7]

Because it is clear that Jesus wants the object of our spirituality to be not only his Sacred Heart, but also the hearts of the young, we can hear him telling us, with the same insistence as Micah Fletcher, “If you have gazed upon one of the least of these suffering ones, you have gazed upon me.” We contemplate the sacredness of their wounds to motivate ourselves for our sacred mission to them.

The active phase of our spirituality needs to deploy itself in institutions where we can salvage today’s Jean Corrois before they become dispirited and callow. Can we also find ways of rescuing the Stephanies, allergic to institutions, who know more indifference than love, along with the Lespinasses, wounded by contact with delinquents? Can we also welcome the Vincents who are running away from a religion that threatens or manipulates them, or who don’t frequent “respectable establishments”? Our spirituality properly lived will send us to the highways and byways to gather youth needing a sanctuary of healing and safe structure. Therein is the real journey of search for new expressions of our spirituality.

Five Wounds of Youth

Brother Maurice’s Rule of Life holds up five wounds of youth for our contemplation: ignorance, neglect, dechristianization, misery, and injustice.[8]

Ignorance is an intellectual wound. Jean Corroi was of the hardscrabble generation thwarted by revolutionary war convulsions. With no schooling, no father, and a mother doing full-time servile work as a washerwoman, he was illiterate, unskilled and consequently vulnerable to every type of exploitation. Today the wound of ignorance scars growing numbers of drop- outs and victims of sub-par systems of education.

Neglect is the fruit of indifference. It creates affective wounds like the estrangement of Stephanie, a burden for her indifferent guardian and an object of contention among her sisters. Starved for affection, she had no place to call home and no capacity to make friends except through manipulation and flirtatiousness. At his Nobel acceptance speech, Elie Wiesel, who spent his childhood in Nazi death camps, said,

“Indifference, to me, is the epitome of evil. The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference. Because of indifference, one dies before one actually dies. To be at the window and watch people being sent to concentration camps or being attacked in the street and do nothing, that’s being dead.”[9]

We see its effects from parents who are minimally present in their children’s lives and in those who resent their exclusion by peer groups and in social media.

Dechristianization is a spiritual wound that Andre saw incapacitating all teens, with the possible exception of Vincent, who made the Catholic restoration an intentional part of his identity in opposition to his father. The banning of religion had been the rallying cry of the revolutionaries; it left children without spiritual or moral references. Today’s generation, often getting no religious upbringing at home, stays away from the Church in reaction to religious hypocrisy, judgmental pastors, and abuse by clergy. Many believing youths feel the wound of ridicule from peers. Dechristianization’s twin sister is materialism, a fascinating seductress with no depth or conviction.

Misery is a material wound. The word in English connotes an emotional state of unhappiness or woe; we feel miserable about many things, like misfortune, illness, or failure. The Rule of Life’s original text, though, is French, and in French the first meaning of misery is material poverty verging on destitution. Jean Corroi and his mother were reduced to misery. Today extreme poverty may not be overt in our country, but we do see child mortality rates rising and the gap between the rich and the poor widening dramatically. Poor children are wounded by malnutrition, unemployment, immigration, and neglect. A recent study shows that one out of every ten schoolchildren in New York is homeless.

Injustice is a social wound, one we saw festering in the prison system of Lyons in a way disproportionately oppressive to children. Another flagrant social injustice to children which Andre Coindre sought to address both at Pieux-Secours and in the village schools he founded was the plague of child labor, which was stripping illiterate youth of their right to education and their hope for a productive future.

The Wound of Injustice

Of the five wounds of youth in the Rule, we will dwell on injustice since it is the most life-threatening. There are some abuses of children which may be too far removed from our world for us to see them through our window. Nevertheless, we can broaden our awareness through the binoculars of advocates who, like the “angels” of l’Antiquaille, know victimized children by their names and by their numbers.[10] Here are some numbers to remind us of children who need our prayer and advocacy:

187,000 [11] students have been exposed to gun violence at school since Columbine. (Washington Post)

Tens of millions of advertising dollars are being poured by e-cigarette makers into targeting teenagers to hook them on their vaping wares. (Centers for Disease Control)

45 children per day are taken from their parents by border control agents as the White House considers another wave of family separation policies to deter illegal immigration. (Vox, 10/18)

250,000 children—some not yet in their teens—are incarcerated each year and prosecuted in adult courts. The US jails more young people than any other nation. (ACLU)

1,000 children are arrested annually for prostitution. The U.S. is a top destination point for victims of child trafficking and exploitation; children are enticed by false promises, and when caught they are charged with crimes. (Bureau of Justice, UNICEF USA)

8,500 late-term abortions (after viability) are legally performed each year. (Centers for Disease Control)

Andre understood that such social wounds as these, imbued in a whole culture and political system, cannot be confronted by individual prophets, no matter how charismatic. That is why he wove a network of prominent municipal leaders organized into boards and financial pledge holders to advocate for justice on behalf of child prisoners. In the response phase of our spirituality, then, more than an individual effort is needed. Yes, individuals are called to contemplate crying needs, to pray for the oppressed, to give them solace and support, and to inform themselves of the issues involved. However, an institutional commitment is indispensable. That is why Father Coindre founded an institution, sought a municipal charter for it, and raised its profile to make it an influential fixture on the charitable skyline of Lyons.

Building the Earthly City

Perhaps it is an anachronism to say this, but in founding Pieux-Secours Andre Coindre was “building the earthly city.” That phrase of Saint Augustine found in the last line of our map gained currency as part of the good news of Vatican Council II. Our spirituality imagines the creation of a new social order out of the old one marked by injustice. “The social order requires constant improvement. It must be founded on truth, built on justice and animated by love.”[12] Our spirituality goes well beyond what is invisible and interior, even beyond what is personal and interpersonal. It also calls for an official response from our Institute and, in turn, from each of its institutions.

Our map (line 14) finally brings us to the destination of our journey, which is the place where our spirituality puts its feet on the ground. That place is somewhere on the periphery of the earthly city where we are being accosted by conscientious contemporaries in civil society such as Messrs. Benoit Coste and Forcrand de l’Isle of the lay congregation who impressed Andre in l’Antiquaille; such as Doug Baker at the Zamzam reunions with his Muslim friend Sara al Badi; and such as the prophets of the Civil Rights era and of the present crisis of climate change.

Our contemporaries are “asking us urgent questions” about issues of justice that are wounding our children. Yes, they want our institutions to protect children from danger and error, but not only that. They also expect us to take a convincing stand on the teachings of the Church on social problems.[13] Those are many, so we must set priorities. First among the problems that Pope Francis is contemplating are powerful assaults on the family and unregulated human excesses causing climate change toxic to those already living in misery.[14] Primary among those Andre Coindre is surely contemplating are the faces of the 60,000 youth under eighteen incarcerated in juvenile jails and prisons in the United States, cut off from their families, disrupted from their education, and exposed to further trauma and violence.[15] Primary among those Brother Maurice must be contemplating are the immigrants and refugees, like those he welcomed regularly into the motherhouse at Arthabaska, being controlled in dehumanizing ways.

A return to our foundational stories shows that we, in contrast to those forebears who gave us the spirituality of the window, have often been blind to or even complicit in the injustices of the society that swaddles us. In Mobile the first missionaries became accustomed to the South’s strict racial segregation system; the orphans they took in were all white. For over 100 years the brothers accepted discrimination without question, never looking out of the windows of their asylum to contemplate the plight of black children without homes.

When, in 1970, the diocese made the decision to integrate the boys’ orphanage, the brother in charge resigned. When Brothers George-Aimé and Andrew finally realized their missionary dream. They went to Lesotho, a country the size of Belgium enclosed inside the maw of the Republic of South Africa. There they accommodated the strict enforcement of apartheid. With other American brothers, they vocally supported the dominant class and relished the entitlements of white power, often inferiorizing their own Basotho brothers in community.

A Heroic Effort

On the other hand, there have been heroic efforts of prophetic response to crass injustice. Mr. Maurice Hartstein, an alumnus of the successor school to Pieux-Secours, Saint Louis College, documented what happened to him, a Jewish boy during the Nazi occupation of France in 1942. When he was 8, he was standing in line with his grandmother to board a bus secretly destined for Auschwitz when a family friend stole him away to Lyons.

Another family contact who lived near the school asked Brother Vital Freycenet, principal, to take Maurice in for hiding and schooling. Vital’s act of civil disobedience saved the boy’s life.

“In accepting me, Brother Vital was taking big risks in occupied Lyons; Klaus Barbie[16] was in charge of the Gestapo in [nearby] Caluire. If I had been discovered, Brother Vital also would have been arrested. He was aware of that from the beginning. I remember how touched I was the day of his death in February 1945 when we students went up in groups to kneel next to his bed and hold his hand. We all loved him dearly for his help during those difficult times.”[17]

Here is a link. [Use the translate button. To return, use back arrow.] http://www.ajpn.org/personne-Maurice-Hartstein-7845.html

On the basis of Hartstein’s documentation of what happened to him, the French association for recognition of the Just among the Nations enrolled Brother Vital in its Book of Guardians of Life in December 2002. The purpose of the honor, as the award certificate says, is to preserve the

memory of his courageous justice for generations to come.

Brother Vital’s story awakens us to the heroic possibilities of working for justice as an educator. He was one hundred percent educator, spending fifty-three years at St. Louis as prefect, teacher and director. He and the brothers who hid children in other schools in France at the time didn’t flinch at taking risks on the road to justice at a time when the merging traffic included machines of war and trains of death.

We have been contemplating the five wounds of youth cited in the Rule of Life and encountered in our stories. What is important to our spirituality is that Jesus tells us the wounds of youth are inseparable from his own five wounds. It is certainly not a stretch to add another line to the blessing he spoke in Matthew chapter 25: “As often as you have contemplated the scars of the least of my brothers, you have contemplated me.”

Far from being a morose exercise, our contemplation of children’s wounds is for them a gauge of hope. “Finally somebody cares about what I’m going through!” “At last, someone’s listening!” “I found a doctor who asked me where I hurt.” Carolyn Byers Ruch, a child victim of abuse, tells us how important recognizing a child’s wounds is: “I was just four when a hired teenage field hand attempted to molest me. Miraculously, I got away, and I told my dad. My father made three important choices that day: He listened to me, he believed me, and he took action. I was one of the fortunate ones—I had a childhood.”

The Epileptic Boy

Jesus wanted to understand what the epileptic boy in Mark’s gospel was suffering and so he took time to listen, without flinching, to the boy’s father’s stories.[18] “Bring him to me. … How long has this been happening to him?” He made the boy’s scars the subject of his prayer, then scolded the disciples for not doing so themselves.

In The Lord’s Prayer, Jesus teaches the disciples how to pray to God for what they need: daily bread, forgiveness, delivery from evil. In the Gospel story of the epileptic boy he teaches them they need to learn to pray for what a wounded child needs.

A Disciple’s Prayer

We, disciples of Jesus’ compassion, have particular interest in learning what he is trying to teach his disciples about prayer. It is this: since we are active disciples in a city of youth, a large part of our prayer has got to be the contemplation of their wounds and addictions. Our spirituality, kick-started by the contemplation of Jesus’ wounds, runs on the fuel of God-given empathy for the pains of youth. The prayer for the young which Jesus proposes to us in the story of the epileptic boy has three distinct phases:

- At the window: we contemplate their personal suffering and the social evil that wounds them.

- In our place of prayer: we ask for the grace of two kinds of empathy—— to feel a heartfelt connection with their suffering, and

–to experience the same emotions God feels toward them. - In the earthly city where we encounter them, we transform our prayer into action—

— by lowering our voice and our defenses to listen actively to them, and

— by entering their life and advocating on their behalf to fight social evil.

Perhaps that outline feels like a sterile prescription. There is a remarkable Caravaggio painting [19] that can lead us to heartfelt prayer.

The artist paints a wholly human scene, without halos or mystical embellishments. This is only one scene in a longer story. The risen Jesus has contemplated Thomas and accepts the apostle’s disbelief as well as his ways of isolating himself. Then, in the scene itself, Caravaggio depicts a double contemplation—of the wound of Jesus and of the incredulity of Thomas.

Thomas’ tattered garb expresses the disgrace he feels about his refusal and his insistence on “the scientific method” of the Enlightenment, of which the painter was a champion.

In the scene, Jesus makes no reproaches, but meets Thomas on his own terms. He presents his own wound as an honor and a part of his identity. He actively draws the doubter’s hand to touch it. The three men’s concerted gaze demonstrates the dynamics of contemplation: curiosity, surprise, wonder, and intimacy. The atmosphere is suffused by a pleasing light of Easter forgiveness.

In the story that follows this one in the Gospel sequence, Jesus speaks first to Thomas and then to us. He gives us a ninth beatitude: “Blessed are you who, not having seen with your eyes, have contemplated with your heart and grasped that new life passes through wounds, yours and those of others.”

Caravaggio’s masterpiece gives us a model for our contemplation of young people. Let us put youth in the place of Jesus. We are their doubters. We will not believe in them unless we probe their scars and contemplate the wound in their heart.[20] Accepting teenagers often involves having to overcome our tendency to reject them when they behave badly. It involves getting beyond conduct that repels us. We must resist defining them by their behaviors. A better approach is to avoid taking their self-inflated stands personally and instead contemplate their wounds. Negative behaviors and refusals are teenagers’ ways of acting out their sufferings. In accepting a teenager as she or he is, we don’t condone repulsive behavior; we correct it, all the while trying to appreciate and heal the wound which it disguises.

We know The Lord’s prayer. We can also learn The Disciple’s prayer. It may not come from the Lord, but remember that disciples are empowered to compose prayers in the Spirit of the Lord.

Make us the eyes of your Body, Lord,

so we can see the wounds

that stifle your children.

Free us to weep with them

as you did over them and their earthly city.

Give them the same place of favor in our heart

that they hold in yours.

Mute our judgments.

Open our ears to their cry.

Draw our hand to touch their scar

that, in your name,

we may believe in them,

will their good,

and act to deliver them from evil.

14

The Croix Rousse: Pieux-Secours

Wounded Youth

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

The Grace I Seek …

Prayer for a Prophetic Consciousness [21]

God, you are turned towards humanity and have feelings toward humanity.

You are dependent on the human voice of prophets to express your feelings.

Generation after generation, you put your voice into the prophets you choose, who feel what you feel, to express silent agony, to give voice to the plundered poor, to decry the profane riches of the world. When you call us to prophecy you want us to abide prayerfully at the crossing point of your heart and ours. You want to pour your emotions into our words.

Help us to understand that your heart is indeed filled with emotion, that you are in fact more emotionally sensitive than the most sensitive among us. When you are moved and affected by what happens in the world, and want to act, open our hearts and shape our words to react on your behalf. Give us a heart to speak not what we feel, but what you hold in your heart.

We praise you for your loving kindness. And is not your love full of emotion? Through us, speak not only your love for the lost, but also your wrath at wrong; your jubilation, and the anguish of your pain. Visit on us your divine pathos and your bright imaginings for the life you hold out to us.

Forever, O Lord, you have wanted to become emotionally involved in human history, with all the heartache that would entail. May our embarrassment about our own emotions never block you from moving our heart or using our voice. May we, as your prophets during this generation, be free enough to let you do and say whatever you please through us.

How often you have told us, Lord, “My ways are not your ways, and my thoughts are not your thoughts.” Teach us your ways. Help us to identify like you do with the steady moan of wounded humankind as well as with its joys and its hopes.

Attune our emotions to yours. Make us prophets who can transform your concerns and anxieties into our own concerns and anxieties. Connect us to you at the heart and enable us to vibrate according to the rhythm of your anger toward the arrogant and your loving compassion for the little ones.

Listen to a youth praying for the heart of a prophet

I Refuse by Josh Wilson

Lyrics

Sometimes I, I just want to close my eyes

And act like everyone’s alright, when I know they’re not

This world needs God, but it’s easier to stand and watch

I could say a prayer and just move on, like nothing’s wrong

But I refuse

‘Cause I don’t want to live like I don’t care

I don’t want to say another empty prayer

Oh, I refuse to

Sit around and wait for someone else

To do what God has called me to do myself

Oh, I could choose not to move

But I refuse

I can hear the least of these, crying out so desperately

And I know we are the hands and feet, of You, oh God

So if You say move, it’s time for me to follow through

And do what I was made to do, and show them who You are

‘Cause I don’t want to live like I don’t care

I don’t want to say another empty prayer

Oh, I refuse to

Sit around and wait for someone else

To do what God has called me to do myself

Oh, I could choose not to move

But I refuse

To stand and watch the weary and lost

Cry out for help

I refuse to turn my back and try and act

Like all is well

I refuse to stay unchanged, to wait another day

To die to myself

I refuse to make one more excuse

‘Cause I don’t want to live like I don’t care

I don’t want to say another empty prayer

Oh, I refuse to

Sit around and wait for someone else

To do what God has called me to do myself

Oh, I could choose not to move

But I refuse

Source: Lyricfind

Songwriters: Ben Glover / Josh Wilson

A Personal Contemplation modeled on the cardinal contemplations.

Return to an experience in your life when you felt close to a wounded or pained young person. Go back in spirit and follow the three movements we have traced in our foundational stories, in the life of our founder, and in the scriptures:

- At the window we contemplate their personal suffering and the evil that wounds them.

- In a place of prayer we ask for the grace of two kinds of empathy—

— to feel a heartfelt connection with their suffering, and

— to experience the same emotions God feels toward them. - In the earthly city where we encounter them, we live our prayer through action—

— by muting our voice and our defenses to listen closely to them, then

— by entering their life and advocating on their behalf to fight social evil.

Pray the Via Crucis of Young People

Contemplate young people in diverse situations of suffering in mainstream society and on the periphery.

— Ask for empathy to suffer with them

— Ask for faith to see the Lord suffering with and in them.

http://boshheartmap.com/ViaCrucisENG/indexen.htm

Contemplation in a desire to feel empathy for children who have been sexually wounded.

Click the audio start button to listen to the true story that novelist Junot Diaz tells of his being sexually abused when he was a child and of the long term effect of that wound, or skip the audio link read the article yourself.

Click the audio start button to listen to the true story that novelist Junot Diaz tells of his being sexually abused when he was a child and of the long term effect of that wound, or skip the audio link read the article yourself.

Allow yourself to feel God’s empathy for him and other child victims of abuse.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/04/16/the-silence-the-legacy-of-childhood-trauma

Footnotes:

[1]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OlJns3fPItE

[2] Brother Marius Drevet, SC, Brother Louis-Andre Bellemare, SC

[3] Brother Roger Bosse, SC

[4] Luke 23: 38-31

[5] cf. Luke: 7:9, 7:50, 8:48, 17:19, 18:42

[6]https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/31/us/portland-stabbing-hero-victims.html

[7] ACWD, Letters, p. 127

[8] See Preamble, 11, 82, 85, 150

[9] Cited in US News & World Report (27 October 1986)

[10] All data are recent and refer to the United States.

[11] Figures refer to the United States.

[12]Gaudium et spes (Joy and Hope), paragraph 26

[13]Rule of Life 151

[14]Synod on the Family in the Contemporary World (2015) and the Encyclical Laudato Si’

[15] ACLU https://www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/youth-incarceration

[16] Known as “The Butcher of Lyons”

[17] Archives of the General House, Rome

[18] Mark 9: 14-29

[19] Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Thomas, 1602

[20] John 20: 25

[21] Based on a reflection of Abraham Heschel