Three Foundational Voyages

Mobile – Dubuque – Basutoland

Brother Maurice used scriptural and theological words to write his map. Like an acorn, which we can think of as a map for the growth of an oak, his map is rich but dense; inspiring but intangible; full of potential, but subject to slow, imperceptible growth. How do we follow such an abstract map? We can’t without help.

In the digital age, there is a how-to video for everything from aerating asparagus to understanding the zen of the zodiac. You can google them. In our cars we have a vocal GPS guide to alert us before each turn. Ships have an inertial guidance system. In the world of spirituality, so far, no how-to’s to help us live our spirituality are on Youtube – although there is a video on our “internal guidance system.”

Foundational Stories

Nevertheless, it is possible to get concrete about navigating our inner spiritual world. Instead of going on line, we can go back in time. We can discover in foundational stories in the Brothers’ history how the ideals of Brother Maurice’s map were lived as a deep and compelling spirituality. Stories from our origins can be living maps for us the way lines and footprints on a ballroom floor map out the steps for dancers who desire, for instance, to master the moves of the merengue.

What follow are three seminal stories of voyages. Taken together, they model how, with practical heroism, our ancestral brothers left footprints for us to step into as we search for how to live the intangibles of our province’s shared spirituality as Brother Maurice has mapped it out.

Paradis  Mobile

Mobile

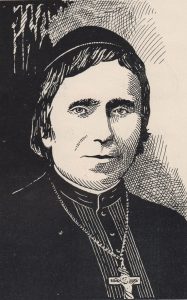

Near the end of his term as superior general in 1846, Brother Polycarp wrote a letter to all the brothers in France. He had just added to the statutes an expression of his desire for the brothers to think beyond France. Within a month, he received an invitation from the bishop of Mobile, requesting brothers to found and run a sanctuary for orphan boys. Bishop Portier let Brother Polycarp know that the boys were actually orphaned twice. He and the sisters who had been caring for them had received a directive notifying them that the sisters’ religious congregation would no longer take in boys. So that meant displacing the boy orphans on short order.

Near the end of his term as superior general in 1846, Brother Polycarp wrote a letter to all the brothers in France. He had just added to the statutes an expression of his desire for the brothers to think beyond France. Within a month, he received an invitation from the bishop of Mobile, requesting brothers to found and run a sanctuary for orphan boys. Bishop Portier let Brother Polycarp know that the boys were actually orphaned twice. He and the sisters who had been caring for them had received a directive notifying them that the sisters’ religious congregation would no longer take in boys. So that meant displacing the boy orphans on short order.

Brother Polycarp’s letter started with words of realism:

“God takes pleasure in being benevolent towards us such that our infidelities don’t turn him away from what he has in store for us. Our institute is moving forward. A new field has just been offered to us in the New World. Who will be the privileged five whom the Lord has chosen for himself to go make known his adorable heart and glorify his holy name on the other side of the Ocean?”[2]

We take up the voyage as told by Brother Stanislaus, archivist, and Brother Macarius, author of A Century of Service.

The chosen volunteers were Brothers David, an experienced teacher before becoming a brother, 31 years old; Placid, a boarding school prefect, 26; Athanasius, a 2nd year teacher, 24; John-Baptist, a tailor and doorkeeper, 34; and Alphonse, a school principal and member of Brother Polycarp’s council, 33, named director of the mission.

The day of their departure was set for September 23, 1846. All the brothers gathered at the place named Paradis. Paradise. What is the origin of the name of this property that the brothers had recently bought along the river Borne on the outskirts of Le Puy? It didn’t come from the brothers. Was that the name of the Roman-era villa whose foundations were unearthed while laying a water pipe through the grounds? Was it the name which, according to ancient documents, designated a cemetery near Le Puy? We don’t know; but its antiquity is beyond all doubt. Paradis appears as early as 1507 on a list of taxable properties and marks the exact spot where our brothers established their motherhouse, their home, their school, their farm, and the formation programs on which they founded their hopes.

Among the brothers bidding the missionaries Godspeed were a number who had also courageously volunteered for the enterprise. With a beaming countenance, Brother Polycarp took the chosen five to his heart, showering on them congratulations and giving them consoling advice. Then the solemn hour approached. The assembled brothers paused before their missionaries and kissed their feet, singing the verse from Isaiah (52:7), “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of those who bring glad tidings, proclaiming peace, bearing good news, announcing salvation, and saying to Zion, ‘Your God is King!’” After the ceremonies, the whole community escorted David, Placid, Athanasius, John-Baptist, and Alphonse to nearby Montagnac, the place where they were to catch the northbound stage coach.

On their way

The last embraces and adieux being made, they set out on their way. They passed through many a storied town made rich in historical association of their beloved country, and acute was their nostalgia as they realized that precious traditions, monuments, cathedrals, manners and customs would be but a memory in a land with no monuments or historic background.

The missionaries traveled by coach as far as Orléans. There they saw with their own eyes that new wonder of the world, a railroad train propelled by steam which actually pulled them all the way to Paris. At Paris they again took the coach, this time to the port of Le Havre. There the five missionaries met four Jesuit priests and two candidates who were to sail with them on the same boat for Mobile. How glad they must have felt to meet traveling companions from near their home in Paradis. These priests had been called by the bishop of Mobile to take charge of the college he had founded at Spring Hill.

They all expected to leave port at once on the Anna, a sailing vessel of 520 tons, but she was not ready to sail until October 27, that is, over a month behind schedule. They were grievously disappointed, for the ship had to be loaded for the voyage, then await a favorable wind. Their delay would indeed have been a great hardship had they not been fortunate in finding accommodations at the hospital of the Sisters of Charity[3] where they were boarded and lodged for about $25.00 dollars a day.

The eager missionaries discovered that they would have to sleep and live in the cargo hold. Once at sea, instead of steering directly for Mobile, the Anna zig-zagged in her course to deliver and take on cargo at every French port along the way. She put in for two days at St. Pierre and Miquelon, two islands south of Newfoundland, where the missionaries were becalmed for two days.

Next they headed far beyond the direct route to Mobile toward the remote Caribbean isle of Guadalupe, which they reached in December and where they were held up for twenty-five days. Once again, cargo had to be unloaded and other merchandise brought on. At port, the missionaries suffered from the great tropical heat, and they were forced to remain on board to get some of the sea breeze. On Christmas day they attended a midnight mass at the hospital of the port, eventually pulling up anchor again to coast along the Antilles and Cuba. There a severe storm battered them. It was by far the worst storm of their voyage, such that the Anna seemed in danger of sinking. Fortunately she was a staunch vessel and weathered it successfully.

Mobile

At last they entered the mouth of Mobile Bay on January 11, 1847. There they transferred to a light schooner, which brought them to the wharf of Mobile to end four storm-tried and seasick months, twice as long as they had expected.

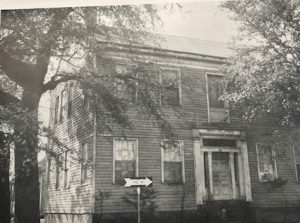

Bishop Portier had impatiently awaited the missionary band, becoming more worried from one day to the next about their safety. It was with tremendous joy, then, that he welcomed them. He led them to a small cottage on Franklin Street across from his residence, a poor abode indeed and nothing like what Brother Polycarp depicted in his rosy letter to the Brothers: “A piece of ground as large as that of Paradis and a splendid house where forty orphans can be assembled is to serve as their home.” Nevertheless, the brothers were content with what they were given, however poor, and the good bishop saw to it that they would not be lonesome. Every morning he himself gave them lessons in English, and sent one of his assistants to continue the same every afternoon.

Some time afterwards, a rented house was bought for them at the corner of Warren and St. Francis streets, and they moved there with eighteen orphan boys sent over by the sisters. There they directed their new “children,” gradually learning the English language and getting acquainted with new foods, manners, and custom, and, of course, the boys who became their new family. In the meantime a larger lot and a roomier house was being prepared. This was St. Vincent’s, into which they moved six months later, on September 1, 1847.

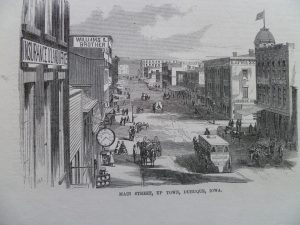

Paradis  Dubuque, Iowa[4]

Dubuque, Iowa[4]

Now that they had a place to live, Brother Polycarp contacted Bishop Loras of Dubuque, Iowa, to establish a farm whose to raise produce to feed the growing number of orphans in Mobile. The bishop had been a colleague of Andre Coindre on the team of priests that gave parish mission revivals in and around Lyons. In 1853 Brother Polycarp sent three brothers and three novices to expand the American mission : Brothers Jean-Claude, Zozime, Ambrose; and novices Odon, Francis, and Claudius.

The land route through France to Le Havre for these Brothers was not very different than the one the Mobile missionaries took; the eight arrived at their ship at the end of April to await embarkation, but there was an unfortunate surprise. Brother Ambrose received an urgent letter from Brother Polycarp ordering him to return to Paradis. A brother in charge of the farm there had made a serious accusation to the civil authorities that Ambrose had taken away from Paradis, without permission, a quantity of valuable seeds. The accusation meant that the leader chosen by Brother Polycarp to direct and finance the Dubuque foundation could not leave France! As soon as the sailboat with his brother missionaries was set to go via New York to Iowa, it sailed without him.

Through the Great Lakes

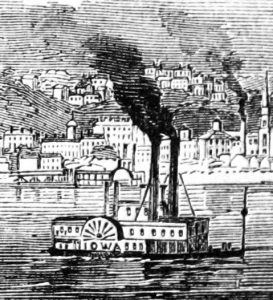

After thirty-six days of sickness and misery, the seven who did sail finally landed in New York. They had to decide which way to take to Dubuque. The sea way was open to them: south on the Atlantic and then west on the Gulf  coast to the mouth of the Mississippi, then north on the river – for a total distance of 3,000 miles, which was about the same as they had already traveled. But they had had enough of the sea. They preferred the northern route, shorter by 1,000 miles. A river boat took them to Albany, a stagecoach to Buffalo, a lake vessel to Toledo, another boat to Chicago by way of Detroit through Lakes St. Clair, Huron, and Michigan. Chicago was only 200 miles from Dubuque, but there was no direct road between the two cities. So they went south by stage coach to St. Louis, a distance of 300 miles, then caught a paddle-wheeler up the Mississippi toward Dubuque.

coast to the mouth of the Mississippi, then north on the river – for a total distance of 3,000 miles, which was about the same as they had already traveled. But they had had enough of the sea. They preferred the northern route, shorter by 1,000 miles. A river boat took them to Albany, a stagecoach to Buffalo, a lake vessel to Toledo, another boat to Chicago by way of Detroit through Lakes St. Clair, Huron, and Michigan. Chicago was only 200 miles from Dubuque, but there was no direct road between the two cities. So they went south by stage coach to St. Louis, a distance of 300 miles, then caught a paddle-wheeler up the Mississippi toward Dubuque.

While berthed in the port of St. Louis they witnessed a spectacular riverboat fire; it was a total loss. A few days later they learned to their dismay that the boat that went up in smoke was the one that was carrying all their chapel furnishings and the farm implements that they were bringing as cargo. The back-breaking loss amounted to $4,000.[5].

On the last stage of their journey, Brother Claudius, one of the two novices, in the act of trying to draw water by throwing a bucket over the side of the boat, lost his balance and fell overboard. The boat stopped at once; the crew gave every possible assistance to rescue him, but with with no success. A week later, his body washed up on the river bank. Charitable hands buried it near the shore and sent his effects to the distressed and grief-struck brothers, who had proceeded on to Dubuque.

Brother Ambrose

The drowning meant that only four brothers out of the group of six arrived at Dubuque on July 15, 1853, bringing with them the heavy pain they bore at the drowning of Brother Claudius. Imagine their surprise when, upon reaching the farm, they saw Brother Ambrose among those who rushed to meet them!

After being abandoned abruptly at the port in France with his seeds, Ambrose prayed with the faith that moves mountains that he could catch up with his brothers. His whole dream of a missionary vocation was at risk. He studied the content of the accusation sent to him by Brother Polycarp that risked ending . He decided that he could defend himself by mail. So he wrote a long letter giving the needed explanations and proofs that he had stolen nothing. Brother Polycarp responded immediately; his answer came by pony express return mail. The police authorities in charge of customs at the port cleared him and Brother Polycarp told him to proceed to Dubuque.

Now he had to grapple with a financial problem. The brothers had left him at the wharf in Le Havre with only enough money to return home to Paradis. How was he to pay both his fare and provisions for the trip? He borrowed whatever funds he needed from a gentleman returning to New Orleans. On the way there, Ambrose offered his services to the kitchen and they were accepted, so he earned free board and a salary as well as a bonus for doing supplementary work. On arriving in New Orleans, he paid off his debt and was flush with cash.

Now, what would he do in New Orleans? How would he make the 1,500 two-week trip upstream by paddle-wheeler to get to Dubuque?

The only route was the Mississippi River, so he quickly took passage for Saint Louis, stowing on the boat a wooden box containing the precious seeds, his meager wardrobe, and a considerable sum of money for purchasing more land plus provisions for the brothers’ community and farm. With everything safely on board, he strolled off to catch a glimpse of New Orleans, but when he returned to the wharf, his riverboat was nowhere in sight. For some reason or other, it had sailed off before the scheduled time. No fear! He had faced such a crisis before. Once more Ambrose was obliged to embark on a substitute boat and, fortunately again, it proved faster than the one with his luggage, so much so that he had to wait for it for twenty-four hours on St. Louis’ dock. His patience was rewarded. When the boat he missed caught up with him up at the wharf, he found his seed crate and steamer trunk intact and untouched.

“New Paradis” Farm

The huge tract in Dubuque that the Brothers had to transform into a farm was 231 acres in area, half woods and half cleared. Their residence was nothing more than a log cabin, crudely constructed, and stuccoed only with mud. Besides planting wheat and oats, the brothers’ days were spent chopping wood, hauling it to the city, and selling it for their livelihood. In the bleak Iowa climate, they had to travel several miles, generally on foot, to attend mass.

Ambrose, a strong man with an athletic build and boundless energy, worked hard at the farm in Dubuque for seven years. He eventually joined the brothers in Mobile with the orphans, where he spent the remainder of his life. His job there too was laborious, doing whatever it took to feed the boys. His services and sense of responsibility were particularly valuable as the Civil War spread and grew more brutal. When, on account of the blockade of the South or the scarcity of money, provisions ran low, he hitched up a mule team, drove out to the surrounding counties, and by dint of begging or bartering, always managed to return what was needed to replenish the orphans’ storeroom.

Hoboken  Basutoland

Basutoland

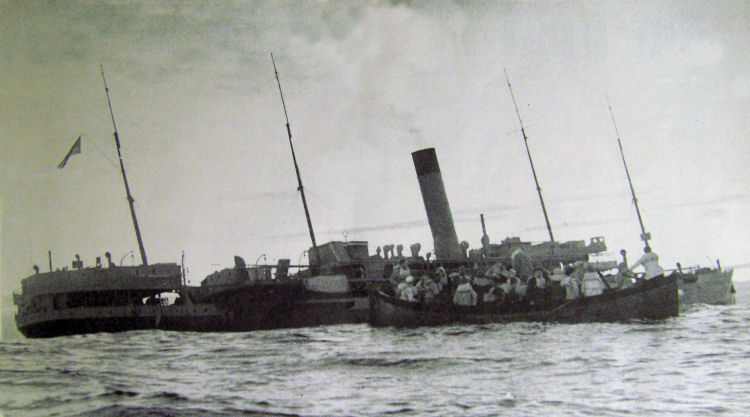

Brothers Andrew Fredette and George-Aimé Lavallé, both Canadian-Americans from Central Falls Rhode Island, were among four brothers who volunteered to replenish the ranks of the original four brothers who made the ocean voyage in 1937 to found a mission in Basutoland in southern Africa. They were eager; right away they began taking lessons to learn the local African language from Canadian priest missionaries who had served there.

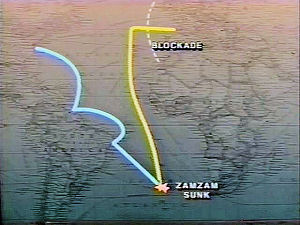

It was 1941. By that time the north Atlantic had become a dangerous theater of World War II. The route to South Africa would normally take them East. However Nazi destroyers and submarines were out on patrol. Out of an abundance of caution, their ship would veer west to take a sea route hugging the coast of Brazil before turning East to South Africa.

Passports of the Commonwealth

The two brothers were told by experienced African missionaries that their Canadian passport rather than their U.S. one would make it easier to travel in South Africa, since it, like Canada, was part of the British Commonwealth. They met twelve priests, Oblates of Mary Immaculate, when they boarded the Zamzam. The ship was an Egyptian vessel with a crew that spoke only Arabic. Besides the Canadian priests and our two brothers, there were over 200 other passengers, most of whom were U.S. Protestant missionary families. To make the steamer invisible at night, the captain ordered all the Zamzam’s windows and portholes to be painted black; lighted cigarettes were not allowed on deck. It left from Hoboken, N.J. March 20, 1941, sailed to Recife in Brazil, April 9, both times in total darkness for fear of detection.

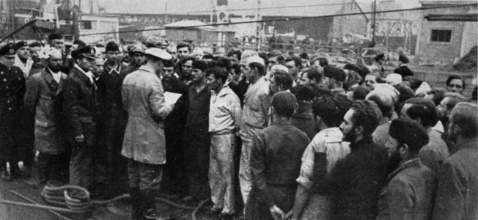

About a week into the journey, in early morning of April 17th, 1941, while most of the Zamzam‘s 242 passengers and crew were still sleeping, the German raider Atlantis fired fifty-five shells. Surprisingly, only nine hit their target, but those nine shells did fatal damage to the Zamzam. After the panic of being rescued at Nazi gunpoint from damaged lifeboats, all passengers and crew members, some critically injured, were boarded onto a prison ship, where they watched the Zamzam sink, then spent thirty-three days in dire conditions of captivity at sea at the mercy of Nazis whose language they couldn’t understand. There was a news blackout. Only after six weeks did the Germans report the event and the fact that all passengers were alive. U.S. newspapers had long since bannered the loss at sea of everyone on the vessel; some families had even conducted memorial services.

Those aboard the prison ship who held U.S. passports were eventually released in Spain and returned home, since the U.S. was officially neutral and not yet in the war. The brothers and the priests, because they had Canadian passports, landed in occupied France to be spirited to Milag, Germany, where they were incarcerated in a prisoner-of-war camp in crowded cells rooms with fifteen or twenty other people. Andrew and George, our two Brothers, ended up each in a separate barrack; they would ultimately spend four years under Nazi guard, prevented by rifle fire even from using the latrines at night. Brother George later said of their captivity, “As for the trials, the loneliness, the searches, the air raids, the starvation, the spies, the torments of being depersonalized, we POWs all know about that. However, as the playwright reminds us, ‘Calamity is man’s true touchstone.’[6] We also experienced some moments of peaceful contentment brought by a letter, or by participation at a church service, or by a budding friendship which would last for a lifetime, or a hope of repatriation, or the euphoria of liberation.”[7]

air raids, the starvation, the spies, the torments of being depersonalized, we POWs all know about that. However, as the playwright reminds us, ‘Calamity is man’s true touchstone.’[6] We also experienced some moments of peaceful contentment brought by a letter, or by participation at a church service, or by a budding friendship which would last for a lifetime, or a hope of repatriation, or the euphoria of liberation.”[7]

Liberation

That hope came true in April, 1945, when British Royal Marines “threw open the gates to welcome liberating forces: tanks, armored cars, trucks, guns, motorcycles and all kinds of equipment. As they roared through the gates, how we cheered and cheered until we were hoarse. The commander of the regiment hoisted a Union Jack up on the flag pole which we had erected a short time before. Then he jumped up on the top of a carrier and called out ‘GENTLEMEN, YOU ARE FREE!’ How we cheered and cheered! Then a Scottish army band struck up the tune ‘God Save the King,’ and, since most of the men were British, how they did sing! How they wept! It was hard to realize that now the war was over and we were free and could go home.”[8]

After several years of decompression and re-adjustment to freedom, both Brothers Andrew and George Aimé finally made it to Basutoland after its name became Lesotho, where their missionary desire became reality.

Conclusion of Foundational Voyages

In summary, on this website have two very different kinds of map for discerning our spiritual voyage:

— One is written in chapter 1 of the Brothers’ Rule of Life in the form of ideals and faith confirmed as a guide by the Church;

— the other was lived out in the true stories of brothers who gave birth to the spirituality of our Brotherhood. Both maps start at the same Point A—a firm belief in a God of love drawing close to us to save us. Both end at the same Point B—far away from home but letting God use our hands and hearts to build sanctuaries throughout the world to care for distressed and vulnerable young people.

Both of the two maps portray Jesus as the heart, the reference point, and the motive of our spiritual voyage. A close reading of both also reveals that the maps from Rule and from life are inspired by some of our Institute’s favorite scripture passages. One is from Isaiah, the prophet whom Jesus quoted to announce his own mission to the lost[9]; found in the 1st letter of John, who tells us that God is Love and Jesus was fully human. The second is in the 2nd letter of Peter, which proclaims that God lives in our hearts and makes us sharers in divinity.

Of the two maps, one is a theological vision. The other retells stories of Brothers of the Sacred whom God sent on mission. The two maps complete each other. While the first gives a spiritual vision of who we are in God’s eyes, the second is a human drama in three acts. If the first could be proclaimed at Sunday mass as the creed of the Brothers; the second could be retold over and over around a campfire. The first charts the part of our heart that channels belief, communion, grace, and longing for transcendence, while the second explores how to expand beyond ourselves as we live in community and with young people. Both are about affection, service, family spirit, an adventurous mission, and shared feelings of disappointment, fatigue, courage, failure, loss, and transformation.

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

Three Foundational Voyages

The grace I seek …

Lord Jesus, during your world-changing voyage through Palestine you crisscrossed the sea and your first disciples lived on the water. I give thanks that you continue to call new disciples from our generation. Give me the grace to ponder the lives and travels of our early missionary brothers so I can learn from them.

Through them, show me how to pay the cost of discipleship. May their voyages inspire my discernment of my vocation in life. Send your Spirit to show me how, inspired by their stories and Brother Maurice’s map in the Rule of Life, to see Brotherhood as a noble vocation and a saving presence for young people.

Connecting the maps

Use your intuition to find connections between the two “maps”: which ideals from the Rule of Life map do you see being lived out by the brothers who made the three voyages?

Imagine yourself in their place

Enter imaginatively into the founding story that most engages you. Take the point of view of one of the persons on the voyage, or watch it as an eyewitness. Allow your imagination to fill in day-to-day details … to hear conversations or join in them … to feel the tensions … to sense what the brothers likely had in their heart and their hopes …

Our inner voyage

The three voyages can be seen as an extended metaphor for our inner spiritual voyage from Point A – experiencing God’s love – to Point B – taking responsibility for showing the personal attention of God for young people who lack hope, faith, or love.

Find in the three stories real or symbolic touchstones to your own spiritual journey:

| Voyage to Mobile | ||

| Ideals/Obstacles to reaching ideals | Founders’ story | My story |

| Experience of God as a loving father /mother | Brother Polycarp’s warm support, the brothers’ blessing, prayer | |

| Emerging spiritual desires | Desire to go beyond France, to generate new life and missions for the institute, union with God | |

| Risks, fears, costs | Leaving home, culture, family, the comfort of Paradis, loss of health, radical life change … | |

| Inadequacies and delays | New language, long layovers, loneliness … | |

| Supportive persons | Brothers, Jesuit companions, B. Polycarp, the bishop, hosts at port | |

| Adversities and disappointments | Storms, lack of home contact and of privacy, discomforts, powerlessness to influence the route, limitations of the ship, Spartan lodging … | |

| Sense of mission, call | Needs of boys orphaned twice, call to spread image of God as a loving father … | |

| Gratifying elements, graces | Being wanted, sought for, welcomed, trusted, sinking new roots in a new culture | |

| Personal gifts discovered | Life experience, patience, ability to respond to needs, language skills | |

| Abiding questions | Will we ever understand the boys we serve and be understood by them?Will we be able to make a lasting presence of the Brothers in the U.S.? | |

| Voyage to Dubuque | ||

| Facing suspicion and false accusations; need to defend self | Ambrose’s letter of accusation | |

| Feeling abandoned and isolated | Left alone on the wharf | |

| Defending self against a superior; not trusted | Letter to B. Polycarp and Paradis authorities | |

| Availability for difficult assignments | Novices leaving country at a young age | |

| Ingenuity in the face of lack of money/ resources | Ambrose working for food and lodging | |

| Dealing with death and tragic loss | Drowning of B. Claudius, guilt at lack of proper burial, lack of closure | |

| Discouraging loss of everything of value | Riverboat fire destroying furniture and implements | |

| Hard work of service | Clearing woods and farm work in a hard climate | |

| Sense of belonging to Church | Long walk to parish; reliance on the bishop | |

| Voyage to Basutoland | ||

| Desire to identify with and build up the Church | Joining with priests and missionary families; passports—Church before patriotism | |

| Victims of violence, persecution | Shot at, imprisoned, panic of near-death event | |

| Professions of prayer and faith to contemporaries | Joining with other missionaries for prayer and mass | |

| Loss of freedom (addictions, injuries) | Internment, oppression | |

| Recovery of freedom | Celebration with British army | |

| Presence and empathy to others’ suffering | Sharing POW cell, mutual comforting, awareness the evils of POW, the holocaust | |

| Facing a real enemy | Humiliation, gunfire, intimidation | |

My own story

After re-reading the notes you wrote above, pray psalm 107 about how God acts in your life.

http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/107

As background music, click on this video clip [music by Peder B. Helland] of a single hiker and reminisce about your personal spiritual journey with its moments of growth, peace, and challenge.

Inspired by the psalm, by Brother Maurice’s “map” and the three missionary narratives, outline the spiritual voyage of your life until now, beginning with the experience of God’s love for you and ending with a commitment in God’s name to the needs of today’s youth. Include in your outline the tensions you have felt between

— your ideals and your obstacles,

— times you grew and times you went backwards,

— experiences of success and of failure,

— feelings of faith and of doubt.

Spend time in prayer of thanksgiving for the voyage you have been able to be make. Write some prayers of intercession for the gifts you will to stay the course.

Psalms: Prayers of Jesus

Psalm 16: The Path of Life http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/16

Keep me safe, O God; in you I take refuge.

I say to the LORD, you are my Lord, you are my only good.

As for the holy ones who are in the land,

they are noble, in them I take delight.

Those multiply their sorrows who court other gods.

Blood libations to their gods I will not pour out,

nor will I take their names upon my lips.

LORD, my allotted portion and my cup,

you have made my destiny secure.

You have measured out for me pleasant places;

fair to me indeed is my inheritance.

I bless the LORD who counsels me;

even at night my heart exhorts me.

I keep the LORD always before me;

with God at my right hand, I shall never be shaken.

Therefore my heart is glad, my soul rejoices;

my body also dwells secure,

For you will not abandon my soul to death,

nor let your devout one see the pit.

You will show me the path to life,

abounding joy in your presence,

the delights at your right hand forever.

Psalm 118: Jesus reflects on his life story

http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/118

Musical Reflection

Listen to and pray with the song Thank you for My Life by Smokie Norful

Prayer of Thanksgiving

From the link below, pray Psalm 145, then add personal verses to name and celebrate our story and your story.

Background music while praying: Classical Strings

[Those having devices with a keyboard: first open the video clip below, then hold SHIFT while clicking the psalm 145 link . To return to this page, click X on the psalm page.]

Classical strings background music

Link for Psalm 145 http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/145

Listening and Mutual Support

In groups or pairs, we listen as others talk about what they find most revealing about the spirituality implicit – and often explicit – in our foundational stories.

Footnotes

[1]Background music while reading— while holding the shift key, click the link below. Then diminish the video to return to the text.

— Classical strings:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjFgeY5gaio

[2] Workbook 2: Brother Polycarp, p. 56-57

[3] The hospitals of the Daughters of Charity, works inspired by Vincent de Paul in the 17th century were not the equivalent of today’s medical centers. Besides caring for the sick, they were religious houses and works of charity to lodge and feed foundling children, unwed mothers, indigent travelers, and the homeless.

[4] Brother Stanislaus, Brothers of the Sacred Heart (Rome), pp. 70-72

[5] Roughly equivalent to $115,000 in 2016 dollars.

[6] Address at a reunion of survivors. Quoted from Beaumon and Fletcher, The Triumph of Honor.

[7] Address at a reunion of survivors

[8] U.S. survivor Jim Russell

[9] cf. Luke 4: 15-21