Lyons: The Hospital of l’Antiquaille

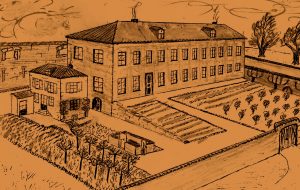

Pieux-Secours, Rural Schools

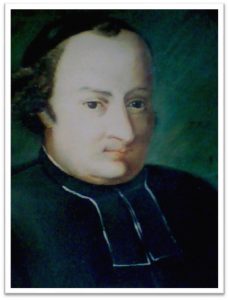

Andre Coindre and Brother Xavier

We open our second cardinal contemplation by looking in on Brother Xavier[1] at his desk in the Pieux-Secours, the sanctuary for at-risk boys that Andre Coindre founded in the Croix-Rousse sector of Lyons. The young priest relied heavily on Xavier first as a layman and then as a brother. So caught up in the founder’s hopes and charismatic vision was he that he came to personify the mission of Pieux-Secours. He was the founder’s beloved disciple.

After spending twenty-one years immersed in the work which Father Coindre had so much at heart, he takes on the role of eyewitness-evangelist by writing his memoirs. The whole project, which Andre had endowed with his own money, inspired with his original vision, and given up his health, is in danger of collapse. Xavier wants to immortalize it and so pass it on to us. He starts his memoirs with these words:

“In 1817, Father Coindre, seeing the hospitals and prisons of Lyons filled with young people, resolved to form a sanctuary to gather them together, away from all danger.”[2]

Andre Coindre at Contemplation

What Xavier is doing is extraordinary. He begins by contemplating the Founder in the act of contemplating young people in the hospitals and prisons of Lyons. He is describing Andre living the spirituality of the window. In the first of our four cardinal contemplations, we watched Jesus’ final days in Jerusalem through the eyes of the two beloved disciples. We will now crisscross Lyons to contemplate our founder through the eyes of the disciple who knew him best and loved his vision first.

Our historians extended and deepened the contemplation Xavier began: Brother Jean-Pierre Ribaut, expert editor of critical editions of five volumes of Father Coindre’s writings with Brother Guy Dussault, plus Brother Rene Sanctorum, author of the essay “Born in Prison”;[3]. Before them, Brother Jean Roure spent years doing painstaking research for his detailed Chronology [4]. They — along with Canadian Brothers Guy Brunelle and Louis-Andre Bellemare — added compelling detail that could be discovered only by intense prayerful research inspired by loving contemplation.

We watch as the thirty-year-old Andre climbs the steps into a raised pulpit to preach, as his clerical superiors attested, “with exceptional talent.” This he did countless times and to outstanding effect. His preaching often had a theatrical flair. Let us picture him at an atonement service on Good Friday in 1818: “He puts a noose around his neck like a criminal headed for execution, and, torch in hand, pleads for pardon while offering himself as a victim of expiation to divine justice.”[5]

We watch as the thirty-year-old Andre climbs the steps into a raised pulpit to preach, as his clerical superiors attested, “with exceptional talent.” This he did countless times and to outstanding effect. His preaching often had a theatrical flair. Let us picture him at an atonement service on Good Friday in 1818: “He puts a noose around his neck like a criminal headed for execution, and, torch in hand, pleads for pardon while offering himself as a victim of expiation to divine justice.”[5]

A month later, as reported by the police lieutenant on duty, “He suddenly takes off his white surplice saying he is not worthy to wear it, puts a noose around his neck and declares that he deserves the shame. Holding the end of the rope with one hand and a candle in the other, he delivers a timely oration. The Sisters and prison administrators present are all holding candles. A prisoners condemned to a life sentence begins to cry out and wail; others are drawn in. Even the Sisters get caught up in it.”[6]

After that sermon, one of Andre’s colleague priests wrote to their diocesan superior to tell him what nobody else noticed. “Coindre was suffering shooting pains of gout to the point of being unable to walk. … It takes magnanimity and courage to be with these unfortunate prisoners, who are often embittered and rebellious. It also takes tact and special aptitudes that are not given to everyone.”[7]

The Founder’s Gaze

Father Coindre’s sensitive contemplation of the plight of prisoners heightened as he regularly visited the penal houses of Lyons. What especially caught his eye and filled his heart was the number of young boys incarcerated together with what he called “perverse men.” There were no cells. Prisoners of all ages roamed in vast halls and yards. They slept on straw covered with tattered rags, passing the day in idleness. Records from the period show that there were 155 children under twelve years of age in the Charity hospice; there were 20 boys and 180 men detainees in the prison of Saint Joseph.

Andre felt urgent compassion for the boys, especially the youngest: “They need personal attention to restore their dignity. They’re guilty at an age when boys are more reckless than incorrigible. They need to be surrounded by good and separated from the contamination that’s closing in on them.”

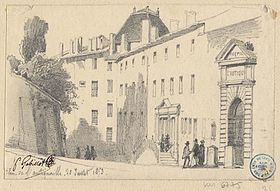

On June 2, 1817 he visits the hospice of L’Antiquaille.

That day he is primed for a life-changing contemplation of his own which he echoes in one of his sermons:

That day he is primed for a life-changing contemplation of his own which he echoes in one of his sermons:

“I see young modest people who are led to visit these prisoners. I see their serious demeanor, their poised attitude, their smiling faces and the serene manner which are their distinguishing features and which form a striking contrast to the hideous faces of the incredulous young people within. They approach. The locks open with great noise; it opens into a dark holding pen. I hear the clamor of the chains as the bodies move and I see an unfortunate one stretched out on the straw, raising his shackles; he thought perhaps that it was the visit of a harsh guard whose job was to ensure his discomfort. The young prisoner’s face is fearful. But he notices that these are angels of peace coming to visit him. Then joy is reborn on his face. Life flows in his veins, he smiles, he hopes, he has a moment of happiness. He kisses the hand of his benefactors and it pains him to see them leave …”[8]

The ‘Angels of Peace’

Andre’s gaze on the suffering prisoners leads him to fix his attention on the visiting group of young lay people whom he describes as “angels of peace.” They are members of a congrégation, a charitable affiliation of visitors led by a banker named Benôit Coste. This association, guided by a church-approved charter, received permission and encouragement from the prison administration in hope of improving the quality of prison life. As time went on, France’s Royal Society of Prisons empaneled the congrégation as a permanent advisory commission to reform Lyon’s prisons. The royal society named its leading member, Mr. Forcrand de l’Isle, a property owner of the city, to lead the commission.

Andre is touched by one of the improvements that Coste and Forcrand de l’Isle were able to show him. It was quite a large hall for housing boys under sixteen years old. In it, Andre visits about twenty boys busy with different tasks under the supervision of a prisoner who himself was condemned, but whose demeanor was appropriate to his role. Besides lessons in religion given by the prison chaplain, on Sundays the children received instruction from the young men and women of the congrégation. They were well-meaning, but Andre sees that their rote method of hammering the catechism into them would need softening to appeal to the children’s better instincts.

Andre is moved to admiration and consolation. He can see the possibilities. Yes, in the prisons there are men “corrupt to the bone,” in the words of Mr. Coste. Nevertheless, Andre’s gaze reveals teenagers who are simply lost. Their weakness or hunger, or even well-meaning but misguided impulses, led them to commit a first offense that landed them in jail. He gets to know abandoned children bereft of parental discipline or support. In Coste and the other members of the lay congregation, he finds kindred spirits who believe that hope in the transformation of these child prisoners must never be lost.

At l’Antiquaille, Andre’s faith in the divinizing power of baptism merges with feelings of empathy passed into his heart from the heart of God. A kind of prophetic imagination is enkindled. His zeal ignites: couldn’t they be given real instructors who can teach them to read, write, and calculate along with basic moral formation? Wouldn’t they be freed from vagrancy and vice by learning an honest trade? Couldn’t they be taken from the prison into a place of refuge and useful employment?

The French school of spirituality

Andre’s formation in seminary had put him in contact with Sulpician priests and their spirituality of the French school. Its leader, Cardinal Bérulle, insisted on the mission of the Church to the poorest: “as often as you do it to the least of my brothers, you do it to me.” (Mt. 25:40) Yet Andre’s clerical superiors, who began to feel angry that “he consecrates himself entirely to good works, notably in the prisons ,” deplored among themselves that he was “wasting on small projects an exceptional talent for preaching.”[9] Theirs was a clerical spirituality centered on sacramental ministry and the preaching of the Word. On the other hand, the volunteers of the congrégation live a spirituality that extends beyond the church to attend to the whole child.

Andre was caught in a dilemma. His heart was in a tug-of-war between loyalty to his priestly duties on the one hand and, on the other, his compassion stoked by a haunting quote from Jesus, “I have come to light a fire on the earth; how I wish it were blazing already.” (Lk 12:49)

He resolved his conflict by making an act of total self-emptying. He resolved to dedicate his wealth and every free moment he had outside of his priestly ministry to rescue as many boys as he could. After two preliminary trials at other locations, he founded Pieux-Secours, a sanctuary where could be released from prison protected by a sructured regime. He assembled leaders of the congrégation and members of the prison committee into a board of benefactors to finance it and businessmen to administer it. These were bold, prophetic decisions. It meant buying a silk-weaving factory and hiring Guillaume Arnaud, the future Brother Xavier, as foreman and master weaver. Andre called the new venture a providence. It was a sanctuary of second chance and a school for life.

Father N. Bez, a priest of Lyon, later published a book on the works of charity in the city of Lyons. Thr book gives an outsider’s perspective of Father Coindre’s innovative initiative for boys: “the purpose of these charitable providences is to bring poor children up religiously … to help them become useful to society by their work [and] by their good conduct. …

“It was for this that was founded, in 1818, the Pieux-Secours, at first for young prisoners who wished to return to the right way, then for young children who want to stay on the right way by learning, under religious teachers instituted to this effect by Father Coindre, a missionary of our city, a trade suitable to their taste and calling.”[10]

Beyond rescue to prevention

The way Andre arrived at his second vocation to be an advocate for youth reveals four movements of the spirituality he developed and bequeathed to us;

1. He enters the world of the incarcerated boys.

2. He contemplates them with attention and faith.

3. Like the prophets, he unites himself to God’s feelings of compassion, and empathy.

4. He acts with self-sacrificing prophetic decisiveness.

Father Coindre does not settle for simple humanitarian gestures of assistance to solve an immediate need; he seeks a long term, definitive solution. He starts by trying to place the released boys in existing schools, but the doors of what he called the “respectable establishments” are closed to them. Those would not take responsibility for such street kids. He gets pushback from educators who say “ they have delinquency in their DNA” … they are “intransigent.” Andre doesn’t see them that way and believes that God doesn’t either. He formulates a pedagogy based on trust in the possibilities of their baptism and of their innate human dignity.

Today we place Andre Coindre’s initiative among works of justice because it goes beyond the transitory comfort charity offered by the “angels of peace” into the roots of an unjust system needing transformation in light of the Gospel.

Yes, Andre was touched by those doing the rescue ministry of visiting youth in prison. All the same, he saw the need to invest himself in a preventive “upstream” solution. He invented an institution to rescue young people from idleness and ignorance in order to keep them from landing in prison in the first place. Inspired by the lay congrégation, he, as an apostle of Christian hope, made a unique contribution to the reform the French penal system and to the lives of the children it detained.

Beyond Lyons to the villages

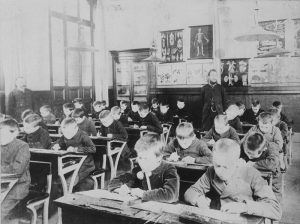

Now, our contemplation takes us out of Lyon to the provincial country towns, where we watch Andre and his missionary team preach parish missions. There he becomes shocked by the pitiful post-revolution deterioration of village primary schools.

Middle-class children in cities had at least some opportunities for education, but those in rural areas were often pressed into field labor. Teenagers couldn’t read or write. Where schools did exist, pupils suffered the violence of unscrupulous teachers with little education and less pay.  Andre began working with village pastors to map out a vision for what would become a faith-based school system born of the core values of his spirituality. He wanted the brothers’ schools to take a God’s-eye-view of the unjust suffering of children. In his heart, he felt God’s heart beating for them, then acted decisively to make systemic change. He founded and staffed with brothers an impressive network of schools in towns whose flagging faith or precarious means had robbed school-age children of hope. In an impressive effort marked by grueling travel by stage coach, with only fifty brothers, most of whom he had personally recruited, he opened twelve schools in three years.

Andre began working with village pastors to map out a vision for what would become a faith-based school system born of the core values of his spirituality. He wanted the brothers’ schools to take a God’s-eye-view of the unjust suffering of children. In his heart, he felt God’s heart beating for them, then acted decisively to make systemic change. He founded and staffed with brothers an impressive network of schools in towns whose flagging faith or precarious means had robbed school-age children of hope. In an impressive effort marked by grueling travel by stage coach, with only fifty brothers, most of whom he had personally recruited, he opened twelve schools in three years.

Prophetic intuitions

Denouncing evil and injustice and then imagining a more humanizing, hope-filled alternative is the work of a prophet. The 2017 province chapter’s Core Statement[11] calling us to the window of a prophetic spirituality to contemplate the needs of those at the periphery is asking no more of us than to follow the spiritual movements of our founder. It was not easy for him. But despite lack of support from his clerical superiors, it was never an “either-or” choice for him. He would feed both fires the Lord lit in his passionate heart even if it meant burning out in a humiliating death not unlike the one that the beloved disciples on Golgotha witnessed, mourned, and eventually proclaimed.

Our foundational stories illustrate how painful it is and how confusing to live in the tension between prophetic risk and established resistance.

For thirty years the Mobile missionaries had labored in what could be called marginal works of the diocese: the orphan asylum and a free school for poor families. They and their pupils suffered from scant financial means. Brother Ambrose, who arrived in Mobile after Dubuque closed, maintained a market stand to sell the produce from his seeds for the orphans’ support.

The brothers had only a single self-sustaining work. The Cathedral elementary school they directed was flourishing. They were able to charge tuition to support themselves and other free works. After nineteen years, the Sisters of Charity who had transferred the original orphan boys over to the brothers, needed more space for their girls. The bishop directed the brothers to move their 390 pupils out of the two-story brick school built for them in 1849 into to crowded and inadequate rooms over a fire station.

The move forced them into a situation where it was impossible to run a school, so it closed after only a year. Gone was the Brothers’ income. Five years later, the diocese built a brand new Cathedral school with large and airy classrooms separated by glass partitions and a suitable playground. But instead of calling upon our brothers to take its direction, the bishop invited the DeLaSalle Christian Brothers in to direct it. Our brothers were deeply offended. They were in effect marginalized with the marginalized.[12]

The Zamzam venture shows how God stirs prophets with passion for the marginalized. It also brings to light how invisible those at the periphery can be to us in the mainstream. Doug Baker is a retired Presbyterian missionary whose cousin Elaine, three years old at the time, had nearly been forgotten on the sinking Zamzam. She was the last to be rescued. Once the war was over, Baker befriended Elaine and attended the Zamzam survivors’ reunions with her. Doing so raised prophetic questions in him:

“We had been celebrating God’s miraculous rescue of the Americans, and especially of the missionaries among them. But hadn’t the exact same God saved the tobacco buyers who were on the same ship? And hadn’t that same God also saved the Muslim Egyptians who worked on the boat? The entire crew of the Zamzam was Egyptian. By virtue of its connection with the UK, Egypt was already an enemy of Germany in 1941. So all the Muslim crew members were treated as prisoners of war. At the missionary reunions, no one knew much about them. … Was I the only person who wanted to know the Egyptians’ experience, which included internment in a POW camp?”

Uniquely among the community of missionary survivors, Baker received a grace of disquiet about the Muslims, who were marginalized by their language and faith and shunned by the establishment religious leaders on the Zamzam. He felt a calling not unlike the one Andre Coindre felt at the Hospice of l’Antiquaille and the one that motivated Brother Polycarp to reach out to the orphan boys turned away by the nuns in Mobile. Baker began asking prophetic questions:

“I remain perplexed as to why we in the Christian community are sometimes so self-absorbed. How do missionaries spend weeks with Muslims, first on an Egyptian ship and then on a German ship, and not even learn their names? Why did the missionaries not seek out information on the Egyptians in the years afterward? Some missionaries wrote books about their own experience. They had lived through such a dramatic moment with the Muslim crew. Did they really think that the only story worth telling was the story of God’s care for Christian missionaries? Had God not cared for everyone on the ship?”

I believe that Doug Baker’s interest in the Egyptians was ultimately a desire God placed in his heart. Are not his questions to the Zamzam missionaries similar to the call of the province chapter to us to go to the periphery to find those no one else cares for? Is his calling to reach out to Muslims not part of God’s recurring pattern? Does God not work to build up a loving, supportive community–the Chosen People, the People of God–-and then, when the community is safe and whole, to challenge it to reach out to peoples abandoned at the margins?

Baker stood at the window to make a contemplation of his own. He committed himself to knowing the story of the Egyptian crew. He challenged the Presbyterian faith community he pastored to intersect, as our five Mobile missionaries did, with a community whose language he couldn’t speak and whose religion he didn’t understand.

To begin, he discovered an account of the Zamzam story written in Arabic and then located someone to translate it. Sara al Badi, whom he called “a generous and brilliant Saudi woman,” became his partner . The close friendship they developed inspired him with a lifelong passion for Christian-Muslim inter-religious dialogue. He connected the Christian believers he pastored with the Muslim communities in his town of Bloomington, Indiana and eventually became director of Presbyterian missionary efforts worldwide until he retired in 2016.[13]

Models for our contemplation

We’ve spent time contemplating Andre Coindre live out his spirituality by looking over the shoulder of Brother Xavier as he wrote his memoirs. We recall its first sentence: “In 1817 Father Coindre, seeing the hospitals and prisons of Lyons filled with young people, resolved to found an establishment to gather them together, away from all danger.”

Before Xavier wrote that sentence, he undertook his own contemplation, spending weeks of sweet time reading every letter the founder had written to the brothers. But poring over them was not enough. With painstaking care, he transcribed the precious manuscripts in his own hand word-for-word as though he was writing them on his heart.

In our turn, let us inscribe this sentence and Xavier’s feelings in our heart as we do scripture verses precious to us. Let us now examine each of its elements and note how we can relate them to our times,

- 1817 It was Monday, June 2 at the Hospital of l’Antiquaille in Lyons that Andre, at age 30, was confronted with the horrors of boys incarcerated with adult criminals. He had gone there there to preach. For us: We need to contemplate realities of today using the language of today. We are present to youth not as preachers, but as educators. Our gifts and profession equip us to instruct, to form, and to give witness by the example of our lives.

- seeing Andre did more than see. He looked, he pondered, he gazed, he cast an attentive regard.

He also listened. He had a personal charism for looking with prayerful depth and grace. Others didn’t see the same way he did, through the grace of baptism.

He also listened. He had a personal charism for looking with prayerful depth and grace. Others didn’t see the same way he did, through the grace of baptism.

For us, all these nuances are contained in the verb contemplate. - hospitals and prisons In post-revolutionary France no social services or schools remained except the police, so authorities used available public buildings to collect the homeless, orphaned, unemployed, vagrant, and criminal.

For us: Today, thanks to Pope Francis, today we speak of peripheries, or the margins, the inner city, the third word, or blighted area as places needing our regard and response. - young people For Andre, at first they were boys under the age of sixteen whom no one else would deal with. Later, in the villages, it was boys unschooled for lack of organized education or for because they were put to work in the fields.

For us: Today it means boys and girls and those with gender issues, usually those of school age, most capable of paying, but often with scant means and, increasingly, with problems of family, of learning, of addiction, or of behavior. The general and provincial chapters, taking the point of view of the founder, is asking us to go beyond established schools to open other windows. - away from all danger Andre describes what he saw, felt, and smelled in prison as “the contagion of criminals.” In his times, exploitation by child labor and other abuses were a way of life, as were severe beatings to discipline children. Andre was prophetic in forbidding all corporal punishment and forced labor; he sought to replace punishment with close supervision, emulation, and prize-giving to reward positive industry and study.

For us: Today we need to create places of sanctuary, to improve the safety of the school environment, of providing positive incentives, proctoring, and correction for those at risk. - resolved This is a strong word in French and in the Gospel. It is the verb used when Jesus “set his face” toward Jerusalem; no one could talk him out of it.

For us: Resolve means to make a firm, even a formal, public decision, as Andre did, despite obstacles, fears, and lack of time or means. Our word resolute captures its sense. Being resolute connotes commitment, determination, perseverance, and strong will. It is a word of action. After resolving to do something to get children out of danger, it was only a matter of a couple of months before Andre found a location for five boys to live and a foreman to teach them weaving skills. Andre was resolute about establishing a permanent institution with a competent staff. For us today, we need a stronger word than goal-setting or passing resolutions. The institutionalizing of compassion was important to Andre, as it should continue to be for us. - establishment The word for what Andre wanted to establish didn’t exist in French. Neither did the kind of institution. He wanted a refuge from prison; a home; a supervised, safe, and structured environment with workshops for learning a productive trade. Since he couldn’t find such a place among the existing establishments of Lyon, he realized that he would have to establish one with his own money. He’d have to invest, find benefactors, and contract professional help. He called what he wanted a providence, a word that evokes God’s care and makes the adult team that staffs it intentional instruments of God.

For us: Today the word sanctuary comes closest to the kind of establishment that flowered from the prophetic intuitions of Andre Coindre.

In summary, our contemplation of the founder’s spiritual heritage, inspired by the French school of spirituality, reveals two movements, each with progressive steps:

SEE with our heart

— Contemplation through the window: gaze attentively upon youth at the periphery

— Empathy: ask the Spirit to place in our heart God’s feelings for those we contemplate

ACT by using our gifts

— Go out: enter their world to meet youth in need face to face and speak to them heart to heart.

–Resolve: with prophetic imagination, consider how to respond in collaboration with others.

–Invest: commit time and money and mobilize the gifts of support persons.

12

L’Antiquaille

Pieux-Secours and Rural Schools

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

The Grace I seek …

Lord, zeal for youth burned in the heart of Father Andre Coindre because you ignited in him the fire of love for the children you set on the earth. Give me more than just a spark of his zeal. I don’t want my spiritual quest to be only a hobby or study, but a daily contemplation and a lifelong investment. Show me clearly how you bestowed a special charism on him, how your Spirit worked in him, and how I can imitate him by multiplying his gift for treating young people the way you mean for them to be treated. Come, Holy Spirit, send down the fire of our founder’s the charism on me. Burn in me as you burned in his compassionate. resolute heart.

Pray Come, Holy Spirit

Contemplation: Composition of place

Brother Rene Sanctorum suggests in his account Born in Prison that we imagine the conditions and the anguish of young prisoners that prompted our founder to see and address their needs. Using Brother Rene’s account below, and with your imagination, dwell on and fill in the scene of our founder’s crucial visit to boys in prison.

Born in Prison June 2, 1817

Brother Rene Sanctorum, Province of France 2016

“In the Prospectus of 1818, Father Coindre made an appeal for pledge holders to support his wholly new and even unusual work which we know as the Pieux-Secours. This approach was new in this era, let alone in Lyons, and he was creating this “to respond particularly to a specific need that no else had yet taken up: to welcome young delinquents on their release from prison.” What place would prisons have in the life of man consecrated to preaching as a Missionary of the Chartreux, and moreover as the assistant pastor of the parish of Saint-Bruno in the Croix-Rousse?

“In his memoires, Brother Xavier explains: “In 1817, Father Coindre, seeing the hospitals and prisons of Lyons filled with young people, resolved to found an establishment to gather them together, away from all danger.”

“How is it that Father Coindre came to undertake this project? To understand, we must review the state of the prisons of Lyons in his lifetime. There were 155 children under twelve years of age in the Charity hospice. After the Revolution, the number of persons detained in the prisons was considerably increased. Why?

“It is because the Revolution decreed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man that the fundamental good of the human person is liberty. Think of the motto of the French nation: liberty, equality, fraternity. From this, those who committed an infraction—having behaved in a manner unworthy of the human person (violence, theft, acts contrary to the public good)—would be punished by the denial of liberty. As a consequence, except for the sentence of death for grave crimes, the Revolution abolished corporal punishment such as inflicting pain or distress (sentencing to service on galleys, mutilation, and whipping) as well as defamatory punishments (processions through the streets in shackles or with humiliating inscriptions). It replaced them all with the deprivation of liberty. The sentences henceforth would consist of periods of imprisonment. This type of punishment had already been used, beginning in 1775, in certain provinces of the Kingdom. Thus, the nation comes face to face with an influx of detainees without having the necessary buildings and functionaries to incarcerate them. That is why numerous Church buildings (abbeys, seminaries, shelters, …), or alternatively castles, were used to satisfy the demand. These buildings were far from having been constructed for their new purpose and this made them, from the outset, impractical and antiquated spaces. We should note that in this era, the use of private cells was not a practice exercised in the prisons of France. The inmates were therefore crowded into common rooms regardless of their crimes.

“There were two prisons in Lyons. The prison of Roanne was a house for the accused awaiting trial. Saint-Joseph Prison was a house of detention for those sentenced to less than one year of incarceration. Outside of Lyons , there also existed a central prison for those inmates sentenced to longer terms.

“Saint-Joseph prison accommodated more than 200 prisoners. Often among them there were convicted criminals destined for the central prison, kept to benefit from the product of their labor, an important resource for the prison. But labor occupied only about 100 prisoners and so, more than half of the inmates lived in complete idleness. And we know that idleness is the mother of all vices; idle hands are the devil’s workshop.

“Elsewhere, there were more children and young people in prison after the Revolution and the Empire (between 1800-1820). Why?

“This was because, although the Revolution liberated the poor from certain burdens that oppressed them (duties, taxes, child labor …), it also dissolved many of the organizations and institutions dedicated to alleviating the poor: corporations [unions for craftsmen], shelters, and welcome centers led by religious or members of the clergy. Thus their misery increased and the means to deal with it decreased. That misery led, especially in the cities, to children in distress, slums, promiscuity, prostitution, illness, abandonment, vagrancy, runaways.

“Subsequently, the Napoleonic wars decimated a generation of young men aged 17-35. Between 500,000 and 700,000 soldiers were killed out of a French national population of about 20 million people. The wars increased the number of orphans considerably.

“It makes sense then that, in big cities like Lyons, delinquency multiplied. As a result, the number of young people thirteen to eighteen years of age – and sometimes even children as young as eight – were sentenced to prison since there was no longer any corporal punishment, such as beatings. Where would these young prisoners be located? There was no plan for supervising them. Thus they were mixed in with the mass of adult prisoners in overcrowded conditions which are difficult to imagine. We can imagine all too well the consequences: humiliation, sexual exploitation, apprenticeship in crime, immoral behavior, and violence.”

Imagine yourself as one of the “angels of peace” who have come to be with the child inmates. Use all of your senses. Watch the gestures and imagine the words of the visitors. Watch and listen as Andre absorbs himself with those who are incarcerated. Listen for their words. What feelings are being expressed? What faith is being lived out?

Address God in prayer

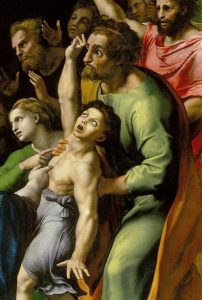

Gospel Contemplation

Do a contemplation of the story of the possessed boy in Mark chapter 9: the boy, the demon, the disciples, the parents, Jesus’ response. Imagine how Jesus bids farewell. Enter into his emotions; formulate what might have been his prayer to the Father after this encounter. What feelings does he express , what faith, what hope?

The Prospectus of 1818

Read the following publication brochure that Andre wrote as an evangelist for youth. In a real sense, it is his epistle to the civic leaders of Lyons; in another sense it is Jesus’ appeal to the Church not to forget a badly neglected generation. In another way it is the prayer of the young people themselves, a prayer they themselves could never express. In it Andre articulates what God put into his heart as a result of his visit to l’Antiquaille. Dwell on its passages. What inner feelings and faith of our founder show through them?

The Prospectus can also be seen as the prayer of Jesus interceding with the Father.

Charitable Institution for Young Boys

There exists in this city a recently established charitable institution which ought to be of interest to all friends of religion and good order. Its goal is to foster a love of virtue and work among young boys who find themselves without shelter or means. It consists of two separate workshops where the children are grouped according to the pattern of behavior they demonstrate. The first is termed the emulation workshop and the other is the probationers’ workshop.

The emulation workshop is intended for poor children from good backgrounds, whose character and morality are carefully attested. These are more often than not young orphans kept out of harm’s way in their early years, but who, lacking in appropriate supervision or pecuniary means, are unable to find an establishment willing to admit them. They are exposed to being led astray either through idleness or to the example of bad teachers. Any child who is of previously questionable conduct is rejected unless a lengthy trial period has provided convincing evidence that there has been a significant improvement in his behavior.

The probationers’ workshop is intended for children who have in the past given their parents serious cause for concern due to their intransigence or the gravity of their offense. Some of them, free-spirited and independent, are reluctant to give themselves over to any sedentary occupations; they often wander on the docks and public squares, a prey to all the evils of vagrancy and to the wiles of unsavory characters. Others have recently been victims of the behaviors from which it is our aim to shelter them. They are young prisoners who, having been incarcerated for a more or less lengthy period, find that no one will give them work. However, they are deserving of the special concern and of individual attention which has for some time been exercised on their behalf in an effort to set them on the path of goodness. Guilty at an age when boys tend to be reckless rather than wicked, impetuous rather than incorrigible, hope for their transformation must never be lost. They must be surrounded with every possible help in order to form them to good habits; they must be isolated, even while in prison, from exposure to the criminal contagion of the inmates.

A farsighted prison administration has conceived a plan and has now implemented it; young prisoners have been isolated from the influence of perverse men. They are being formed within specially provided barracks in the two prisons of Roanne and Saint-Joseph. Placed under the supervision of a staff member who encourages them to diligence and teaches them the fundamentals of our religion, they have for the most part shown appreciable signs of contrition and improved behavior. Since the inception of this program, several of the boys considered sufficiently reliable and possessing sufficient instruction have been admitted to first Holy Communion, and others are also receiving instruction for the reception of this sacrament considered so vital to our Christian faith.

Nevertheless, all these noble efforts would soon come to nothing if provisions are not made for them to extend beyond the prison walls. Like causes produce like results. And experience shows that such children soon return to prison if they are left a prey to people and circumstances like those responsible for their original downfall. What therefore is to be done? They are rejected wherever they go. Honest employers are unwilling to hire them. All the religious establishments refuse to admit them, despite the fact that substantial sums have been offered to cover the cost of apprenticeships. Are they therefore to be left to return to their former ways? Are all the noble expectations for them to perish, due to an inability to provide suitable accommodations for them? No, such a thing would be out of keeping with Christian charity. A safe haven must be found for them provided with workshops where they can be taught an honest trade. They need a sound grounding in the knowledge and practice of their religion and thus become both good Christians and good laborers so as to one day be upright heads of families and loyal subjects.

An establishment of this kind exists, and it is located in the parish of Saint-Bruno at No.3 Chemin des Remparts. Its premises are large, airy and walled in. Its two workshops are already furnished with equipment for several trades, with well-trained instructors able to form their students well. Boys already admitted into this establishment have conducted themselves most satisfactorily. They are all engaged in the manufacture of velvet or silk fabrics, either plain or patterned, using the “Jacquard” method. They receive room and board, are clothed and have their laundry done on site. They are given lessons in reading, handwriting and arithmetic, and all costs are met by the establishment. As for religion, it holds there a preeminent position. It is, after all, the primary goal of this charitable work. It is nurtured within the minds and hearts of the pupils with the utmost zeal and concern.

It goes without saying, however, that a fledgling establishment such as this is far from being self-sufficient. It has already been the beneficiary of a substantial outlay of funds. But more money will be required to meet the costs of taking on more pupils and to increase the number of machines for the trades, as well as for the purchase of beds and other necessary equipment. It may even become necessary to take on master tailors and master cobblers to teach such trades to children who show aptitudes for such trades.

Those responsible for initiating this new venture hope to find collaborators who will assist them in developing this work, which has already taxed them beyond the limits of their resources. They have concluded that an annual appeal for pledges might be a good way to achieve this end. And they are therefore launching this appeal and are proposing it to the kind generosity of all the people of this city. The suggested amount for the pledge has been set at the modest sum of twenty-five francs, which can either be paid in one sum or in three installments.

The pledge-holders shall be listed among the patrons of the institution. They shall receive information on the progress of both the institution and its pupils. They shall have the right to submit the names of candidates for any available places. They will benefit, during their life and after their death, from the prayers which the pupils raise every day to heaven for their benefactors. They shall have the reassuring consolation of having made an enormous contribution to the material and spiritual well-being of these children, who might otherwise forever languish in misery and be a prey to depravity. They shall have the glory of propagating sound doctrines, of encouraging religious fervor and probity among the largest segment of the working class, whose industry has been from time immemorial one of the principal sources of the prosperity of this city. Finally, they shall be contributing at one and the same time to the glory of God, to the salvation of neighbor, to the interests of this city, and to that of the nation.

In Lyons pledges may be made at the following premises:

Mr. Jaricot, merchant, Place de la Comédie,

Mr. Mathon, merchant, Place de l’Herberie,

Mr. Bonnet, merchant, Place Louis-le-Grand,

Guyot Brothers, booksellers, Grande Rue Mercière,

n° 39, at the Trois Vertus Théologales

In Lyon, v. CUTTY PRESS, N° 8 Place Louis-le-Grand, facing the Rhône.

Footnotes

[1] Baptized Guillaume Arnaud, Andre Coindre recruited him as a layman to be foreman and professional mentor of boys learning silk-weaving trades. Andre later invited him to be the first among the ten first brothers who would form a religious community at the heart of the refuge.

[2] Brother Xavier [Arnaud], Memoirs, Rome, 1995

[3] Published in 2018, the 200th anniversary of the founding of Pieux-Secours

[4] Brother Jean Roure, SC, Father Andre Coindre, 1787-1826, A Chronology (Rome, 1987)

[5] Roure, p. 69

[6] Ribaut, Annuaire 96: 9-10

[7] Ibid. p. 12

[8] Notes de Prédication, p. 85

[9] Annuaire 96:7

[10] Roure, p. 63

[11cf. Home page, Welcome menu, “Invitation of the Provincial Council”

[12] A Century of Service, p. 118-119

[13] Doug Baker, “Who Did God Save When the Zamzam Sank?” Evangelicals for Social Action, April 12, 2016