Somewhere around the middle of each of our foundational voyages there was a point of no return at which the brothers had to face the realities of their mission and commit themselves to it with a firm and full response.

The six-man party going to Dubuque, after landing in New York, had endured a laborious 1,300 mile riverboat and stage coach route to Saint Louis before starting the definitive leg of their 350 mile voyage upstream on the Mississippi. Their trial began in port. From the wharf, they had to watch helplessly as the moored vessel holding all their furnishings and farm

implements burned out of control. They lost everything. Then, shortly after they launched to continue on to Dubuque, they were even more devastated.

One of the two novices drowned, heaved overboard in a maladroit maneuver. The paddle wheeler killed its engine and dropped anchor, delaying its upriver launch some very painful days as frustrated local authorities tried without success to retrieve Brother Claudius’ body. Remember, the brothers had already left Ambrose behind in Le Havre. That left four dispirited survivors of the six who had departed together from Paradis. Once they made it to Dubuque, they had to salvage their sense of mission and buck up one another’s courage while doing survival tasks like sealing their log cabin dwelling with pitch to insulate themselves against the hard winter.

The Zamzam missionaries, overtaken by their wartime nightmare in mid-Atlantic, violently lost their boat, their freedom, their original mission, their identity, and any certainty that they would make it out of Germany alive. The re-activation of their missionary dream would take years to motivate.

As for the Mobile mission team, it arrived hale and hearty on the butterfly-shaped tropical island of Guadeloupe in the Antilles. Although they were just sixteen degrees above the equator—compared to Le Havre’s fifty—they had still not left France, as Guadeloupe was a French colony. After two months of voyage, they were still at home among fellow countrymen.

The Mobile Missionaries

The Anna anchored at Point-à-Pitre for twenty days to discharge and reload cargo.  That two-way reciprocal action is a metaphor for interior work the five had to do. The prospect of leaving the last outpost of France geographically was a radical thing – they might never again set foot in the homeland.

That two-way reciprocal action is a metaphor for interior work the five had to do. The prospect of leaving the last outpost of France geographically was a radical thing – they might never again set foot in the homeland. On top of that, to leave French culture, language, and ways of thinking behind will be even more difficult and life-changing for them because it will require fundamental self-emptying. The editor of the Annuaire, in reading letters from these five, is impressed with how well they were letting themselves be changed. He is surprised. To him it doesn’t sound like their letters were written by Frenchmen of their time:

On top of that, to leave French culture, language, and ways of thinking behind will be even more difficult and life-changing for them because it will require fundamental self-emptying. The editor of the Annuaire, in reading letters from these five, is impressed with how well they were letting themselves be changed. He is surprised. To him it doesn’t sound like their letters were written by Frenchmen of their time:

“How much grace and simplicity we can admire in the narration! There is nothing of what we are used to: descriptions of historic fortresses, feudal manors with crenellated stonework, poetic windmills … or purple- and golden-topped mountains. No! What the places look like is not important to them. Totally dedicated to the mission, they are not interested in the scenery.”[1]

After twenty-five days in Guadeloupe, Anna finally weighed anchor for the final leg of her voyage, and the five watched the last moorings of their French identity drop behind the horizon. The next letter they wrote was all about their vulnerability, self-emptying and embrace of loss, even though those words don’t appear on the stationery.

“We were brought to the orphanage where we found twenty-five orphans, all very young, and it was there that the lot of our worries and confusion began. Imagine, if you can, our painful position. Without knowing a word of English, we had to direct them and take care of all their needs. We tried communicating with signs, but it was Greek to them, except for one or two! Instead of getting discouraged, we put ourselves to work day and night learning English. We started grasping a few words here and there, and after three months we could make ourselves understood. But what English!”[2]

Self-emptying

Although the new missionaries didn’t call what they were doing in Mobile “self-emptying,” that’s what it was, a long period of giving up part of their identity and of expending enormous energies to be present to the children abandoned to their care. The emptying process made them vulnerable. There are few things that make us more vulnerable than having our language taken from us. The five together knew less English than any single one of the children they were caring for. They had no choice but to become like children. In doing so they modeled for us the beginnings of a self-deprecating approach to spirituality required by the needs of our mission.

They show us that the finest response to our divine giftedness is the decision to empty ourselves. We make that response—or not—in total freedom; there were no repercussions from Jesus for the nine lepers who went off dancing in a show of self-loving wholeness. That we respond at all might be God’s hope, but the decision rests with us.

In the concentration camp, Brothers George-Aimé and Andrew were emptied of the most painful and humiliating loss of basic human rights. Not only did they endure privations, including free use of the latrine, but their captors assigned them to separate barracks for the express purpose of isolating them. Their vocation was purged from them. They were emptied of their humanness. George-Aimé suffered severe mental and emotional stress.

The brothers in Dubuque had to surrender their whole nine year venture and walk away from it. Brother Ambrose had been chosen to go there in part because he was a muscular young man with broad shoulders and an athletic build. He put seven years of his life into clearing forest land, hauling the wood he had cut to sell for income, and making the farm productive. To abandon it – by coincidence during Passion Week – required heroic self-emptying.

Transferred to Mobile, he transported seeds for a large garden and was charged with supplying food for the orphans, a task complicated by the chaos of the Civil War, particularly during the blockade of the port of Mobile. Inflation soared. Cash lost all value. To put bread on the table, he hitched a team to a wagon and made the rounds through rural counties in Alabama to beg and barter his way through the crisis. In the long run, he emptied himself of his health, eventually becoming crippled by rheumatism caused, doctors said, by “exposure.”

That we respond by a life of other-centered self-emptying is a call we hear by contemplating the example of Jesus. In the Garden of Olives he lost first blood by sweating in anguished prayer over his decision to empty himself out as a sacrificial lamb. His self-emptying culminated the next day at the Sacred Heart event when, splayed in complete vulnerability on the cross, the lance drew his last drops of blood.

Response Phase of our Map

The response phase of our spirituality begins by contemplating the wound caused by Jesus’ self-emptying. We take in the excruciating scene. On one level, we can regard the wound in his side as something that victimized him. Doing so arouses in us admiration for his heroism as well as gratitude for the depth of his love. It also stirs up empathy for the naked shame he felt and the physical agony he endured. However, staying at the level of an observer would miss the point Jesus made at the supper the night before.

Breaking the bread and pouring the wine, he said, “Remember me. Do this.” Be broken. Pour yourself out. Those at the Last Supper may not have

understood, but Paul, who, like us, never met the historical Jesus, got it: “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ?”[3] Paul takes his response to the ultimate level, that of participation. He did throughout his life what Jesus had done. He emptied himself: “I am being poured out like a libation.”[4]

Being Wounded

To reach that level, Paul accessed his own wounds so he could better identify with Jesus. In that way he both robbed them of their power over him and continued the self-emptying that Jesus began. To help us reach the same level of participation, Paul shows us the importance of turning our contemplation from Jesus’ wounds to our own. By seeing his wounds as participation in the woundedness of Jesus, Paul arrived at the point of boasting about them.[5]

Our spirituality, born of the thrust of the lance, is a spirituality of woundedness. The Sacred Heart is a wounded heart. We all have been wounded. Some of us bear scars from birth. Others of us from our youth: abuse, neglect, fears. We have been stifled or marked by failure or emotional breakdown. We develop addictions. We suffer loss. We succumb to evil. We recoil from betrayals and disrespect. We are deprived of affection, recognition, or even of basic necessities of life. We bear physical injuries, deformities, and debilitating disease.

It is valid for us to do what Paul did, envision himself wounded upon the cross: “I have been crucified with Christ.” Our wounds are part of who we are. They set us apart. They are beyond our control. They identify us with Jesus: “[the wounded] Christ is living in me.”[6] The Rule of Life tells us that our wounds and limitations have saving power because they give us “greater sensitivity toward the spiritual and material sufferings of others” and can “reveal to them the compassion of the Lord.”[7]

Unless we make the ownership and the contemplation of our own wounds a part of our meditation on the Sacred Heart event, we will be unable to empty ourselves. Instead, we will act out our wounds, becoming self-absorbed and possessed by grudges or resentments.

We would do well to borrow from the insights of Saint Teresa of Avila. She said “God enters us through our wounds.” She acknowledges that it takes a tremendous amount of humility, integrity and self-honesty, together with charity and forgiveness, to acknowledge our shadow and to allow the long, arduous work of its transformation to begin. The parts of us that have been repressed and hidden, after coming to full consciousness for recognition, will be healed and transformed through God’s acceptance and love.[8]

If Teresa is right that God enters us through our wounds, we can’t forget that God does so as Communion. When we invite God in, we can expect that healing or self-acceptance will be accomplished in us through other human beings who flesh out God’s divine providence: our Brothers, friends and ministers, our spouse, counselors, and colleagues whom we trust.

In Teresa’s experience, befriending our wounds, like all friendship, is not without risks. That is why the Rule of Life considers that, in disclosing the adversities of our interior life, it is important to seek support from trusting conversations with capable authorities, spiritual directors, and ministers of reconciliation.[9] The Mobile brothers opened themselves to the pastor of St. Vincent, Father Hackett, who welcomed them into the parish, taught school with them, and helped them through times of alienation from diocesan clergy. After his betrayal in the seed debacle, Ambrose sought help from Brother Polycarp and Brother Alphonse. And Brothers George-Aime and Andrew trusted their peer missionaries, the Oblate priests, as well as key members of the Protestant missionaries.

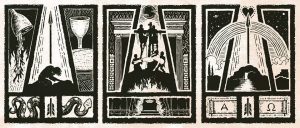

There is a sculpture that illustrates God entering through our wounds as Communion. The figures in the sculpture represent the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit ministering to a vulnerable and solitary person.

Its title is The Compassionate Trinity. The sculptor describes her intent:

“In the center there is a human figure who represents all of us, who, with our fragility and our sufferings, our problems and refusals, are protected and enveloped by divine compassion. The Father, in a circle at the right, leans over us, welcomes us, kisses us, hears our supplications and sustains us. In a circle at the left, the Son, accepting our fragile condition, comes down to our level and shows his immense love as service to neighbor. From above, the Holy Spirit, warming us, opens our eyes and reveals our mission to us.”[10]

Our wounds can be graces that help us empty ourselves of our egocentrism. Just as the Sacred Heart event of Jesus’ piercing is a sacrament – the source of all sacraments – so our wounds, accepted, forgiven, opened and shared, can unleash graces of self-emptying for ourselves and of compassion for others.

By his wounds we are healed. O happy fault! O necessary sin that earned for us so great, so glorious a Redeemer! [11]

9

Guadeloupe

Self-emptying

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

The Grace I Seek …

Lord, you shocked your disciples when you announced,“If you want to be my follower, you must deny your very self, take up your cross each day, and follow in my steps. If you try to save your life you will lose it, but if you lose your life for my sake, you will save it.” (Lk. 9: 23-24) Your words are hard, Lord. Give me the courage to welcome them and the wounds that are the cross I bear. Help me to accept even my most shameful wounds serenely, the way you bore your cross. Fill me with trust that my wounds, like those you bore, can become transfiguring light for others.

Contemplation of the self-emptying of Jesus

Roc O’Connor, “Jesus the Lord” (click on box).

Wounds of the Apostle Paul Warren Gage, January 12, 2013 http://www.luke2427.com/wounds-of-the-apostle-paul/

“I bear on my body the marks of Jesus” Gal. 6:17

There is a pattern to our sufferings in this life. For Christians, no hurtful wound is merely random or meaningless. It is the goodness of God’s providence that makes our sorrows meaningful, for suffering always precedes glory, as the Savior said of his own wounding (Luke 24:26).

Paul encouraged the little, struggling church in Galatia with these words full of gospel hope, “I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me.” (Gal 2:21). Paul’s identification with Jesus’ death and resurrection is explicitly applied to all believers by the apostle. “If we have been united with him in the likeness of his death, certainly we shall also partake in the likeness of his resurrection.” (Rom 6:5). Our suffering, like Christ’s suffering, will result in our glory. That is the gospel. Our cross will be followed by our crown. This is the gospel teaching of Jesus (Luke 24:26). It is the comfort of Peter’s joy (1 Pet 4:13), the confident assurance of Paul (Rom 8:18), and the crown of Jesus’ reward (Heb 2:9). We bear in our body the marks of Jesus’ death in order that we may likewise bear in our body the glory of his resurrection.

There is a pattern to the many wounds suffered by Paul and recorded in Scripture. That pattern, the composite portrait made of all his suffering, movingly portrays his own theology of conformity to Christ’s suffering, showing that Paul bore scars that were like the scars of Jesus. Consider the “marks of Jesus” displayed in the body of Paul. Paul’s back was scarred by the rod and the scourge (Acts 16: 22; 2 Cor 11:24). Three times he prayed, like Jesus, that God would remove his suffering caused by the thorn he bore in his flesh (2 Cor 12:7-10). His unnamed wound, which God did not remove and to which he, like Jesus, submitted his own will, was a metaphoric “thorn” which recalls the Lord’s own suffering of the crown of thorns and, perhaps also, the wounding in his side. Paul was scarred with the lethal piercing of the viper which fastened to his hand from the sticks he had gathered for the fire on Malta (Acts 28:3). Moreover, while in the Philippian jail, his feet were pinned by the “stocks,” which in the Greek original is “wood,” the same word reserved elsewhere in Acts by Luke only in reference to the cross of Jesus (Acts 16:24; cf. Acts 5:30, 10:39, 13:29).

Paul’s composite scars create an iconic image of the suffering of Jesus. The thorn in the flesh, the scars on his back, the serpent’s piercing of his hand, his feet pinioned by the wood of the stocks. And like Jesus, whose last wound poured out water and blood (John 19:34), Paul wrote of his own approaching martyrdom, “I am poured out like a drink offering” (Phil 2:17; 2 Tim 4:6). Moreover, just like Jesus accepted death with the cry, “It is finished,” (John 19:30), so Paul confronted his coming martyrdom with the claim, “I have finished my course” (2 Tim 4:7). Paul’s sacrificial death emblematically described the last death offering of the Savior Paul served so faithfully, even unto death (Psalm 22:14).

Prayer using Broken Vessels by Hillsong

Meditation—The Five Wounds treated in the Rule of Life

We are wounded and we wound others. I recall and reflect on my own woundedness by discovering experiences during my life corresponding to the following citations from the Rule of Life and related scripture passages.

It would be helpful to have a Rule of Life handy to read the cited lines in context. A PDF file of the complete rule can be found by clicking the Rule of Life menu at the top right of on the Home page

WOUNDS As “consecrated persons and apostles”

Refusals and delays are part of our lives. 117

Overwhelmed

…overwhelmed by tasks 36

…the ways of the Lord are obscure 104

…the experience of our personal limitations 152

Jeremiah 20: 7-18 You duped me, O Lord.

http://www.usccb.org/bible/jeremiah/20

Indifference 70

… isolated 36

…loneliness 73

…love is not always accepted 117

…the indifference of our society 152

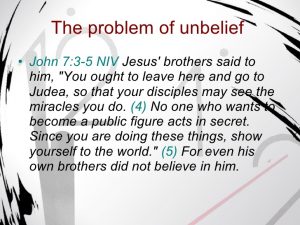

Read John 7: 5 His brothers did not believe in him.

Selfishness

…individual selfishness 82

…interior discord 105

…the resistance of evil 152

…abuses and errors 211

Read Genesis 37: 16-28 Joseph is maltreated by his brothers.

http://www.usccb.org/bible/genesis/37

Physical Suffering

…sick and elderly confreres 37-38

…hardships 117

…Apostolate of suffering 161

Read John 5: 1-17 Patience and hope of a paralytic

http://www.usccb.org/bible/John%205

Failure

…our limitations and failures 81

…failures 152

…fraternal correction 25

Read Luke 22: 54-62 Peter’s humiliating failure

http://www.usccb.org/bible/luke/22

As from Jesus’ wounds, grace flows from our wounds

Judith 8: 14. 24-27 God tests us to strengthen us for others.

Deuteronomy 30: 1-6 God circumcises our hearts.

Romans 2: 29 Circumcision of the heart

R 152 b,c,d Our wounds make us more sensitive to others.

R 118d Our wounds make us a sign of Christ.

R 114 the wounded heart is a source of grace

R 5, 26, 84, 99, 104 Graces of conversion

Scripture: Self-emptying Philippians 2:6-8

Adam and Jesus

In the “self-emptying” hymn of Paul in Philippians 2:5-11, Ralph Martin sees six parallels between Adam, the first human, and Jesus, the new human.

Adam set in motion the mythic pattern, which we call original sin, of desiring what we see others desiring. That pattern is an impulse that threatens us with the temptation of grasping unto ourselves. In contrast, Jesus set in motion a new pattern of self-emptying.

- Adam grasps at being like God. In a spirit of competition and rivalry with God, he desires to know as much as God knows. Jesus, by contrast, chose not to grasp or cling, even to equality with God. Rather he emptied himself, becoming nothing.

Christ the New Adam Rembrandt - Adam spurned being God’s “pet” human, God’s earth creature. Jesus,

however, took the human condition upon himself freely and fully, becoming poorer and lowlier by taking the form of a slave. - Adam exalted himself while Jesus humbled himself.

- Adam became disobedient unto death, while Jesus became obedient unto death, even the scandalous death on a cross.

- Adam ate from a tree, grasping for the light of divine knowing; Jesus hung from a tree, embracing the darkness of human unknowing.

- While Adam was banished from the garden and the tree of life, Jesus was exalted to glory and has become the way to Life.

Rivalry with God and self-promotion, characteristics of the first human, continue to tempt the human heart. Only by a sincere and total gift of ourselves to God and one another can we grow to our full personhood and come to resemble Jesus. We take Jesus poured out on the cross as exemplar of the teacher and model on whom we form ourselves into persons who pour out ourselves for others. Jesus emptied himself of divinity in order to reveal perfectly the true nature of the Divine. His poured-out Love unceasingly waters creation into life. Instead of consuming the earth, we pour out love and communion that water the new life of the earth.

Catherine T. Nerney, SSJ, at the Sisters of Saint Joseph Federation Leadership Assembly, November 2007

A Prayer of Self-emptying by Casting Crowns

Our wound, our Shadow Teresa of Avila

http://makeheaven.com/a-psychological-view-julienne-mclean.html

Self-Emptying: Richard Rohr

Once you have allowed yourself to be vulnerable and received infinite grace, you will find ways to let the love flow through you, serving others. People filled with the flow will always move away from any need to protect their own power. They will be drawn to the powerless, the edge, the bottom, the plain, and the simple. They have all the power they need; it always overflows, and like water seeks the lowest crevices to fill.

Stages of Grief in the face of loss

https://grief.com/the-five-stages-of-grief/

Suffering in old age: Listening

https://care-ethics.org/why-we-need-narratives-about-suffering-in-old-age/18 Apr 2018

There is a collective aversion when it comes to facing the realities of old age, or so John Harris argued in The Guardian last February. Harris is, of course, not the first to point at a widespread public revulsion of growing old, and the association with loneliness, isolation, powerlessness and uselessness. Nowadays, many of us view a longer life as a mixed blessing. We embrace the so-called vital ‘third age’, but we collectively turn our backs to the frail ‘fourth age’. I believe we should control this tendency and fully face the fourth age including its difficulties.

It is easily understandable that people want to age as healthily, actively and independently as possible. We seek to achieve a ‘good’ old age that is characterized by personal contentment, physical health and social well-being; and these aims underpin most gerontology research. Driven by the ideal of liberating the aging from their suffering, a great deal of effort is put into counteracting stereotyping and negative framing of old age through promoting good and successful ageing.

This somewhat one-sided emphasis on the bright side of ageing makes it more difficult to acknowledge the darker sides of growing old. It leaves us with a sense of a widening gap between the fit and the frail. Staying on the positive side makes it harder for us to take a realistic view of what our own old age might contain: the prospect of increasing dependency, and the decline towards decrepitude and death. It also – and this might be even worse – worsens the difficulties we might have in giving proper attention to older people already dealing with the suffering dimensions of their aging.

I also read an interesting article by Chris Gilleard on suffering in old age. In his article, Gilleard goes one step further by making a strong moral plea for addressing the topic of suffering much more emphatically in society as well as in ageing studies.

It so happens that this is what my own research is about, namely mapping out the despair of people suffering from life in old age, and I use the word ‘despair’ here with care. By means of in-depth and longitudinal qualitative research, I have been trying to shed light explicitly on the lifeworld of those older people who consider their lives to be over and no longer worth living. Many of them even have thought of a self-chosen and self-directed death.

My research has convinced me of the need for more personal stories about suffering in old age for at least three reasons, namely: 1) understanding, 2) recognition and 3) consolation. First, stories about sadness and suffering associated with age are very important for enlarging our understanding, both at a personal and societal level: What does the suffering mean for the person involved? How and to what extent is life threatened in their eyes? Researcher Andrew Sayer (2011) has highlighted the importance of taking peoples’ concerns seriously, not merely to recognize them as private emotions, but to view them as illuminations of what is happening in wider society. What needs to be taken seriously? Sayer says: “Needs, desires, suffering and a lack of well-being indicate a state of our world and some aspects of that world that should be changed.” Personal stories should never to be reduced to (or even neglected as) ‘arbitrary, subjective experiences’, but should serve as a springboard for on-going public debate on the place and role of elderly in society.

Secondly, most of the older people with a death wish whom I interviewed over the last few years experienced an enormous loneliness around their difficulties. They often lacked a sense of recognition by others. They had the impression that their close ones and professional careers tended to avoid talking about their suffering, let alone about their wish to die. Instead, these careers — with the best of intentions no doubt — tended to distract their attention by talking about fun things (i.e. nice weather or nice planned outings). The deepest wish of those I interviewed was, however, not that somebody would distract their attention or try to ‘solve’ their suffering – often they didn’t even believe that it was possible to solve their suffering. Rather they wished for somebody who just acknowledged their struggles and was willing to encounter their pain and sadness by listening to and connecting with their stories.

When someone acknowledged their sadness and suffering, it was often deeply consoling. I fully agree with Gilleard that making ourselves a witness of suffering can be seen as a basis for an ethic of human dignity and a call for solidarity with the suffering elderly. If we want to counteract the social neglect, exclusion and/or distress of the oldest old, we should control the tendency to turn our backs to the distressing (and often unsolvable) sides of the “fourth age” and instead pay full attention to struggles that people living the fourth age might experience. We should suppress the impulse to immediately dissolve or intervene their pain.

Els van Wijngaarden, Academic Visitor at the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing in Feb-March 2018.

Self-emptying through Sickness and Suffering

Nicodemus Tebatso Makhalemele

During the celebration of the fifth World Day of the Sick held at the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Fatima, in Portugal, the Holy Father addressed those who suffer in body and spirit. He urged them to resist the temptation to regard pain and suffering as an experience which is only negative, to the point of doubting God’s goodness. He proclaimed the Church’s conviction that “in the suffering Christ every sick person finds the meaning of his or her afflictions. Suffering and illness belong to the human condition, We are fragile, limited creatures, marked by original sin. In Christ, who died and rose again, however, humanity discovers a new dimension to its suffering: instead of a failure, it reveals itself to be the occasion for offering witness to faith and love.”

Addressing thousands of pilgrims gathered at St. Peter’s Square, Rome, to celebrate the eighth World Day of the Sick, Pope John Paul II told them that the Christian community is celebrating the year 2000 as the Holy Year. This special event in the Church should, among others, be an occasion for what the Pope called “the purification of memories.” He went on to say that much-needed conversion and purification will need to be promoted in the world of suffering and health. He invited the suffering and the sick to accept their pain and illness and turn them into a source of purification and salvation for themselves and for others. They should bear in mind that “just as the Resurrection transformed Christ’s wounds into a source of healing and salvation, so for every sick person the light of the risen Christ is a confirmation that the way of fidelity to God can triumph through self-emptying until the Cross and can transform illness into a source of joy and resurrection.”

The celebration of the ninth World Day of the Sick took place in the Cathedral of Sydney, Australia, in 2001. In his message to the sick and suffering the Pope invited them to contemplate the mystery of the incarnate Word, in which human pain finds its supreme and surest point of reference. He insisted that the Christian faith teaches that even in suffering, pain, illness or death, humans are not beyond God’s reach. Talking about his own experience of ill-health, he told the suffering and the sick that he has come to understand more and more clearly its value for his ministry and for the church’s life. He went on to invite the suffering all over the world to “contemplate with faith the mystery of Christ crucified and risen, in order to discover God’s loving plan in their own experience of pain. Only by looking at Jesus, “a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Is. 53:3), is it possible to find serenity and trust.”

In the same message Pope John Paul II addressed special words to the sick and suffering who find themselves in hospitals and treatment centers. He disclosed that for him these places are like shrines where people participate in Christ’s paschal mystery. In these centers and institutions the Gospel message of hope should be proclaimed so that the sick and suffering encounter in Jesus the Savior who will answer their existential questions and fulfill their deepest aspirations. In the Holy Father’s own words: “Only in Jesus the divine Samaritan is the fully satisfying answer to the deepest expectations of every human being in search of peace and salvation. Christ is the Savior of every human person and of the whole person.”

In 2003, the Holy Father presided over the celebration of the eleventh World Day of the Sick, held in Washington, D.C. He invited American Catholics and people of good will to bear renewed witness to charity, so that the presence of Christ the Redeemer of humanity may be felt especially in the numberless persons enduring physical and moral suffering. The Pontiff went on to express his faith that it is especially in those tragic human experiences that “the Christian is called to bear witness to the consoling truth of the Risen Lord, who takes upon himself the wounds and ills of humanity, including death itself, and transforms them into occasions of grace and life.”

Music Meditations

1. Our Wounds and Brokenness Pray Broken Vessels by Hillsong

2. Acceptance Prayer Anthem by Leonard Cohen

The birds they sang

At the break of day

Start again

I heard them say

Don’t dwell on what

Has passed away

Or what is yet to be

Yeah the wars they will

Be fought again

The holy dove

She will be caught again

Bought and sold

And bought again

The dove is never free

Ring the bells (ring the bells) that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

(there is a crack in everything)

That’s how the light gets in

We asked for signs

The signs were sent

The birth betrayed

The marriage spent

Yeah the widowhood

Of every government

Signs for all to see

I can’t run no more

With that lawless crowd

While the killers in high places

Say their prayers out loud

But they’ve summoned, they’ve summoned up

A thundercloud

And they’re going to hear from me

Ring the…

3. David’s Wound Hallelujah byLeonard Cohen,

David, flawed and sinful, was “a man after God’s own heart.” (Acts 13:22) There is joy in our woundedness because it gives us “greater sensitivity toward the spiritual and material sufferings of others” and they can “reveal the compassion of the Lord.” Rule 152)

Now, I’ve heard there was a secret chord

That David played, and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The minor fall, the major lift

The baffled king composing “Hallelujah.”

Hallelujah (repeated)

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew ya

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne, and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah.

Hallelujah (repeated)

You say I took the name in vain.

I don’t even know the name.

But if I did, well really, what’s it to you?

There’s a blaze of light in every word

It doesn’t matter which you heard,

The holy or the broken Hallelujah

Hallelujah (repeated)

[spontaneous verses …]

I’ve done my best, it wasn’t much

I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch.

I’ve told the truth, I didn’t come to fool you.

And even though it all went wrong

I’ll stand before the Lord of song

With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah. Hallelujah

Homily By His Wounds, We are Healed

Fr. Joseph Mungai Good Friday, April 14, 2017

St. John the Apostle Awasi Catholic Church, Kisumu Archdiocese, Kenya

This is a very wounded world we live in. No one is exempted. This is what original sin is all about; because of our wounded nature, we keep on hurting each other, consciously or unconsciously, even though we desire to love and care for each other.

Indeed, when we reflect on the gospel text (Jn. 18:1-19:42) we can identify with the different characters in the Passion play. In fact, this explains why on Palm Sunday and on Good Friday, the congregation is asked to speak for those characters who denied Jesus and the crowd who called for His execution. In so doing the Church reminds us that all of us have different roles to play in the suffering, not just of Christ but of the world.

Let us not be naïve and think that we are suffering because others have done us injustice. We have our part to play in every problem, misunderstanding, quarrel or conflict.

So today, if you feel that you are alone in your suffering, assuredly you are not. The world suffers too. Most of all, Jesus suffers in His humanity and His love. If you feel betrayed in a relationship — with your spouse, your children, your close friend — remember Jesus endured that as well.

He was abandoned by His apostles; even Peter, James and John could not keep vigil with Him in His final moments. But what is most heart-breaking is that one of the Twelve betrayed Jesus and sold Him out for money! If you were Jesus, you would have been heartbroken too. No wounds pierce our hearts deeper than those inflicted by people we love.

Equally painful for Jesus was to know that His chief apostle, Peter, lacked the courage to acknowledge their friendship even to a maid and some servants. That is how we feel too. In times of trouble, our bosses do not stand up for us. In times of failure, even our parents and loved ones condemn us. In times of need, our friends play us out and abandon us. Few stand up to defend us publicly, although in private they say they support us. This is the truth. Many lack courage to risk their lives to stand up for others even though they are right. We all want to be accepted and to be popular. We see which direction the wind is blowing and accordingly, we choose what is in our best interest; not for what is right. This was the case for Pilate as well. He saw the devious intentions of the priests, but instead of taking a firm stand on Jesus’ innocence, he allowed the popular wish of the people to determine the fate of Jesus for fear of losing his office and position.

Then there are others who are enslaved by past hurts and resentments. We find it difficult to forgive those who have hurt us, much less to forget the psychological pain. Some of us carry our wounds for years. We cannot forgive our siblings or even our parents for failing us. Indeed, much of our pains today is due to the inability to let go of those hurts that wound us deeply. We bear so much resentment. But what we see at the cross is the silence of those who had been wounded. Jesus was silent and only uttered words of excuses and forgiveness for His enemies. Mary, the mother of Jesus, grieved silently with Him but uttered no words of anger or hatred. With Jesus, she would have said in her heart as well, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they are doing.”

Finally, some of us cannot accept our illnesses, our immobility or are still grieving over the death of a loved one. We are angry with God that we are not able to look after ourselves. We cannot accept that He took away our loved ones, especially if they had suffered a sudden death, such as in an accident, or even from a short illness. Departures are always painful, as they create a vacuum in our lives, knowing that we cannot see or touch or hear them anymore. Someone has to be blamed and we cannot understand why God is so cruel to take away someone whom we love and depend on so badly, leaving us alone.

Jesus showed us how to suffer positively. Again, Isaiah said, “Harshly dealt with, he bore it humbly, he never opened his mouth, like a lamb that is led to the slaughter house, like a sheep that is dumb before its shearers never opening its mouth.” (Isaiah 53:7) It is not enough to suffer in life like a stoic but to suffer in a redemptive manner, using our sufferings to transform ourselves and to inspire others. It is how we suffer that will inspire others and give hope to them. When we visit patients in hospitals, we see some who are full of bitterness. We leave the hospital feeling sad. But if we meet patients who are suffering with love and faith in God, we leave feeling hopeful and encouraged.

Jesus is our leader in suffering and in salvation. He perfected His love for God and for us through the sufferings He went through. His love of God was not sheer sentimentality, but a giving of Himself and His life.

Before His enemies, Jesus was faithful to His identity. Twice He said to those who arrested Him, “I am He!” He was hinting at His divinity. Before Pilate who thought he had power over Him, He said, “You would have no power over me if it had not been given you from above; that is why the one who handed me over to you has the greatest guilt.”

In no uncertain terms, He made clear His mission and identity. “Yes, I am a King, I was born for this, I came into the world for this; to bear witness to my truth, and all who are on the side of truth listen to my voice.” This is in direct contrast to many of us who succumb to our enemies. Instead of being true to our faith, we give in to the pressures of society. We adopt secular values, consumerism, and anti-life opinions.

We are called to contemplate the Crucified Christ. In the first reading (Is. 52:13-53:12) the suffering servant will be “lifted up, exalted, rise to great heights.”

This foreshadows Jesus’ death on the cross. Indeed, the sufferings of the Crucified God on the cross is something beyond human imagination; that God would die in Christ on the cross. Truly, “His soul’s anguish over, he shall see the light and be content. By his sufferings shall my servant justify many, taking their faults on himself.” When we know that God suffered, we can accept the mystery of suffering since God was not spared from suffering either.

The image of the Crucified Christ gives us hope and courage. Regardless of our weaknesses, we know that Christ will understand, for He has been through all trials, sufferings and temptations. “Since in Jesus, the Son of God, we have the supreme High Priest who has gone through to the highest heaven, we must never let go of the faith that we have professed. For it is not as if we had a high priest who was incapable of feeling our weaknesses with us; but we have one who has been tempted in every way that we are, though he is without sin.” So none of us should ever feel unworthy or hopeless.

We can “be confident, then, in approaching the throne of grace, that we shall have mercy from him and find grace when we are in need of help.”

“During his life on earth, he offered up prayer and entreaty, aloud and in silent tears, to the one who had the power to save him out of death, and he submitted so humbly that his prayer was heard.” With Jesus, in times of trials and even death, we too must say, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” Let us not be afraid to accept His divine will and find peace for our souls.

Through suffering, we will also learn obedience. Mary and John and a few women stood by Jesus at the cross. He was not alone. And just as He sent Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus to give Him a proper burial, so too, God will send the most unlikely people to help us endure the storms of life.

Footnotes

[1] Annuaire 2, 114

[2] Ibid.

[3] 1 Corinthians 10:16-21

[4] 2 Tim 4:6

[5] 2 Corinthians 11:30

[6] Galatians 2:20

[7] Article 152

[8] cf. Julienne McLean, Psychology and Carmelite Spirituality for Today

[9] Articles 134, 173

[10] Brazilian Sister Caritas Müller, Ediçois Paulinas

[11] Antiphons of the Easter Triduum liturgies