Deciding whether to embark

—Do I really want to go?

—Do I really want to go?

At this point, we have to ask ourselves, “Do I really want invest energy, prayer, and experiences to develop a Brothers of the Sacred Heart spirituality?” We’ve been exploring maps found in the Rule of Life  and stories of real Brothers committed to the mission of creating sanctuaries for young people. Your ship hasn’t sailed yet; it’s still in port. You’re figuratively still at Paradis in 1846 with everybody else, holding in your hands Brother Polycarp’s letter of invitation to embark on a spiritual voyage to America. In the letter he makes no bones about portraying how difficult the voyage and resulting change of life might be: “Let us probe our hearts and dispositions. … Let us see if and to what extent we are willing to sacrifice our comforts, freedom, health, strength, our entire life , for so noble a cause.”[1]

and stories of real Brothers committed to the mission of creating sanctuaries for young people. Your ship hasn’t sailed yet; it’s still in port. You’re figuratively still at Paradis in 1846 with everybody else, holding in your hands Brother Polycarp’s letter of invitation to embark on a spiritual voyage to America. In the letter he makes no bones about portraying how difficult the voyage and resulting change of life might be: “Let us probe our hearts and dispositions. … Let us see if and to what extent we are willing to sacrifice our comforts, freedom, health, strength, our entire life , for so noble a cause.”[1]

Before going any further, we need to do what Brother Polycarp did with the brothers. He asked them individually whether they wanted to embark. Do we want to jump aboard for this spiritual voyage? Rather than a copy of Brother Polycarp’s letter, what we have in hand is a call from the Brothers of the Sacred Heart and from your teachers. That call repeats Pope Francis’ summons to what he called “the periphery.” Answering that call will involve embracing a common spirituality with Brothers and the lay partners in their schools, accompanying them, and living their spirituality out in a way that will make you God’s earthly presence to persons who until now have inhabited only the periphery of your life.

Before going any further, we need to do what Brother Polycarp did with the brothers. He asked them individually whether they wanted to embark. Do we want to jump aboard for this spiritual voyage? Rather than a copy of Brother Polycarp’s letter, what we have in hand is a call from the Brothers of the Sacred Heart and from your teachers. That call repeats Pope Francis’ summons to what he called “the periphery.” Answering that call will involve embracing a common spirituality with Brothers and the lay partners in their schools, accompanying them, and living their spirituality out in a way that will make you God’s earthly presence to persons who until now have inhabited only the periphery of your life.

Saying Yes

Saying Yes will involve you in new ways of praying, of doing ministry, of dealing with doubt, of thinking about others, and about trusting God. Every brother at Paradis had to decide whether he wanted to invest or not. Saying “yes” has to be a free choice. There may be many reasons to say, “No, my boat is berthed, my anchor’s cast. I’ve looked at the map and heard the stories, but I can’t. It’s just not me.” You could say, “I’m just not a very spiritual person. … I’m too young … I have so many questions … .”

On the other hand, there are also many reasons to give it more thought. The passengers on the Zamzam represented nearly a dozen faiths and had a wide spectrum of motives for signing the ship’s manifest. These questions might help your discernment:

— When have you ever had a surprise insight that deep down in you there’s intriguing spiritual energy that’s part of your make-up? … that, mixed in with your doubts and convictions, there’s more depth to you than you give yourself credit for?

— When have you ever ended a particularly hectic few months by saying to yourself, “It’s crazy that I let myself get this involved! There’s got to be a way to chill down. I can’t keep up this restless pace! It’s burning me out. I can’t get involved in something this big or this deep. … ”

— When, after feeling that spiritual practices like prayer, church, sermons, and retreats are repetitious and numbing, have you ever told yourself, “This can’t be the way it’s supposed to be.” Or “Maybe I’m doing it wrong or perhaps somebody who taught me was misguided.”

— When have you felt a moment when your heart went out to someone suffering an insult or acute need, or someone starved for attention, or to a cause crying out for help, but you let the feeling pass and moved on? When, on the other hand, have you responded and felt right about it?

Surprises, questions, doubts, feelings, and sudden insights or spontaneous gestures make up the richness of our spiritual life. How we weigh them and respond to them will define our spirituality.

There are some very good and noble reasons to stay open to saying Yes.

Nonetheless, there are some questionable spiritualties that we need to reject with a definitive No.

No to a spirituality of illusion

When Pope Francis concluded the 2015 worldwide gathering of 270 Catholic bishops who deliberated on difficult issues of family life, he warned against a temptation among the bishops to practice a “spirituality of illusion” that ignores people’s struggles or sees things only as we wish them to be. “A faith that does not know how to root itself in the life of others remains arid and, rather than oases, creates other deserts,” he said.

The illusion occurs when “we are able to walk with the People of God, but we already have a set schedule for the journey, where everything is listed. We think we know where to go and how long it will take; we expect others to keep to our rhythm. Their problems are a bother to us. We run the risk of becoming like the crowd in the Gospel who shush and block the blind man Bartimaeus from telling Jesus of his problem. Jesus, on the other hand, wants above all to reach Bartimaeus, who finds himself out on the fringes.”[2]

No to a spirituality of “looking good”

In today’s Church, there is a generation of churchgoers and clergy who equate spirituality with the practice of sacramental correctness or with nostalgia for traditional worship that surrounds us in heavenly mystery. In this spirituality, it’s not grace unless it comes through formal sacraments or stained glass windows. It makes appearances – vestments, music, art, incense, décor, rituals, and being admired – central.

It seems this has always been a danger. Saint John Chrysostom identified it as early as the 4th century. He asked his priests, “You want to honor the body of Christ? Don’t despise him when he is naked. Don’t honor him in your church with silk vestments while you leave him outside suffering from the cold and lacking clothes. Honor Christ the way he himself wants to be honored. What is the point of setting his table with golden vessels while he himself is dying of hunger? Remind yourself that Christ is really going around like a stranger with no place to call home while you are embellishing floors, walls and columns in his name. You are attaching lamps with golden chains and you don’t want to see that he is chained up in prison. When you decorate your churches, don’t forget your least brother in distress, for that temple is worth more than the other.”[3]

No to a spirituality by proxy

For too long we’ve considered spirituality something we leave up to the brothers, to pastors, or other church professionals. “It’s part of their vocation,” we assume. “They assure the spiritual dimension in their houses at times of prayer.” Although that attitude may be born of respect and trust toward the Brothers and the clergy, it was clearly not the intention of Father Coindre when he planted the original seeds of our spirituality. He sowed them freely so they could be shared by persons of all vocations. Besides the group of priests with whom he formed a traveling team to give parish missions, he gathered around himself businessmen, women active in parish social work, blacksmiths, and colleagues of all ages and vocations.

Among his first initiatives was to gather a group of twenty-four young ladies who devoted themselves generously as disciples of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to the corporal and spiritual works of mercy and to the “sanctification of self and of others.” He served as their guide and joined in their conversations about their spiritual lives.[4]

To found his first sanctuary for neglected boys, Andre relied on lay men, professionals and civic leaders on the one hand and competent craftsmen in the silk industry on the other. The foundation of the brothers didn’t come until three years later. And he asked the brothers to serve under the direction of a lay board. He formed these lay leaders, in his own words, to “propagate sound doctrines and encourage religious fervor and probity among the working class while giving glory to God and salvation to neighbor.”[5]

His attention to the spiritual formation of laity did not stop with adults. He formed the boys themselves, both in the prisons he visited and in the sanctuary he founded, to “offer prayer addressed each day to heaven.” Through the diverse staff he put together, he nurtured “with the utmost zeal and concern the love of religion within the minds and hearts of the pupils.”[6]

We cannot expect those hired as campus ministers and religion teachers to act as our proxies in prayer and spiritual life. All of us are called to the same common spirituality, no matter what our individual vocation might be: single, married, ordained, brother, sister, or student.

As Pope Francis said to pilgrims gathered in St. Peter’s Square, “Holiness is a gift that is offered to all, without exception, so that it is part of being Christian. All are called to holiness in their own state of life. It is by living with love and offering Christian witness in our daily tasks that we are called to become saints. Always and everywhere you can become a saint, that is, by being receptive to the grace that is working in you and leading to holiness.”[7]

Response to Brother Polycarp

So Brother Polycarp’s question to the Brothers gathered in Paradis remains in our ears: “Will I offer my name to take part in the voyage which is our common spirituality of the Heart of Christ?” The response to that question requires a thoughtful and prayerful effort at discernment.

4

Paradis— Do I want to go on the journey to find my spiritual vocation?

Discernment whether or not to embark

The grace I seek …

Lord how many times have I felt a call similar to Brother Polycarp’s to leave what I call home to join in a mission that would mean following you?

How many times have I resisted those calls? How often have I felt myself resonate with them? Slow me down to give this decision the consideration it deserves because I believe it ultimately comes from you. Send your Spirit over me to overcome my indifference with honest discernment like yours for forty days in the desert.

Setting the tone

Listen to and meditate on The Summons by John Bell

One of the most important intentional communities of the 20th and 21st centuries is Scotland’s Iona Community.

Founded on the remote Island of Iona in far western Scotland, the community traces its inspiration back to the 6th century, when St. Columba found his way from Ireland and established an outpost from which he evangelized all of Scotland. Eventually, he spread a Celtic form of Christianity that still resonates strongly today.

John Bell (b. 1949) grew up in a rural town south of Glasgow. He received degrees in arts and theology from the University in Glasgow. and appointed youth coordinator for the Presbytery of Glasgow.

In 1980 he was admitted to membership of the Iona Community, having applied not primarily because it was a place of liturgical celebrations but because it was “a place where the potentials of the socially marginalized as well as the socially successful would be attested.”

Since then he has become the international troubadour of the Community, guiding its publications in worship and music, preaching at conferences around the world and composing many songs that enumerate the themes of the Community.

This is perhaps the most famous of Mr. Bell’s hymns. It appeared initially in the first collection of music produced by a Worship Group called “Heaven Shall Not Wait. The song asks a series of 13 questions.

Characteristic of Bell’s style, the text is prophetic, using many words not usually found in traditional hymns. “The Summons” of Christ is a calling to a radical Christianity. Jesus calls us to “leave yourself behind” and to “risk the hostile stare” (stanza two), “set the prisoner free” and “kiss the leper clean” (stanza three), and “use the faith you’ve found to reshape the world around” (stanza four).

The tune is a traditional Scottish ballad. Mr. Bell often uses traditional melodies from Ireland, Scotland and England for his hymns. These tried and true tunes make the songs not only singable, but often provide singing that engages people in a fuller participation in the congregation’s song, stretch their faith and encourage them to live in a manner that reflects justice.

© 1987 The Iona Community (Scotland), admin. by GIA Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

To listen:

Will you come and follow me if I but call your name?

Will you go where you don’t know and never be the same?

Will you let my love be shown? Will you let my name be known,

will you let my life be grown in you and you in me?

Will you leave yourself behind if I but call your name?

Will you care for cruel and kind and never be the same?

Will you risk the hostile stare should your life attract or scare?

Will you let me answer prayer in you and you in me?

Will you let the blinded see if I but call your name?

Will you set the prisoners free and never be the same?

Will you kiss the leper clean and do such as this unseen,

and admit to what I mean in you and you in me?

Will you love the “you” you hide if I but call your name?

Will you quell the fear inside and never be the same?

Will you use the faith you’ve found to reshape the world around,

through my sight and touch and sound in you and you in me?

Lord your summons echoes true when you but call my name.

Let me turn and follow you and never be the same.

In Your company I’ll go where Your love and footsteps show.

Thus I’ll move and live and grow in you and you in me.

Expressing Doubts: The Saint that is Just Me by Danielle Rose

Gospel passages

These stories ask for a Yes or a No in a climate of freedom. Re-read one or two of the familiar passages listed below. Click the link under them to read noteworthy commentaries.

Mark 10: 17-22 A man searching

Pope Benedict’s Message for World Youth Day

[scroll down for the Pope’s message]

VATICAN CITY, MARCH 15, 2010 (Zenit.org).- Here is a translation of the message Benedict XVI wrote for the 25th World Youth Day, celebrated Palm Sunday 2010

My Dear Young Friends,

This year we observe the 25th anniversary of the institution of World Youth Day, desired by the Venerable John Paul II as an annual meeting of believing young people of the whole world. It was a prophetic initiative that has borne abundant fruits, enabling new generations of Christians to come together, to listen to the Word of God, to discover the beauty of the Church and to live experiences of faith that have led many to give themselves totally to Christ.

The present 25th Youth Day represents a stage toward the next World Youth meeting, which will take place in August 2011 in Madrid, where I hope a great number of you will return to live this event of grace.

I would like to propose to you some reflections on this year’s theme: “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” (Mark 10:17), treating the gospel episode of Jesus’ meeting with a rich young man.

1. Jesus Meets a Young Man

And as he [Jesus] was setting out on his journey,” recounts the Gospel of St. Mark, “a man ran up and knelt before him, and asked him, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” And Jesus said to him, “Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. You know the commandments: ‘Do not kill, Do not commit adultery, Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Do not defraud, Honor your father and mother.” And he said to him, “Teacher, all these I have observed from my youth.” And Jesus looking upon him loved him, and said to him, “You lack one thing; go, sell what you have, and give it to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” At that saying his countenance fell, and he went away sorrowful; for he had great possessions” (Mark 10:17-22).

This account expresses effectively Jesus’ great attention to youth, to you, to your expectations, your hopes, and shows how great his desire is to meet with you personally and open a dialogue with each one of you. In fact, Christ interrupts his journey to respond to the young man’s question, manifesting full availability to him, who was moved by an ardent desire to speak with the “good Teacher,” to learn from him how to follow the way of life. With this gospel passage, my Predecessor wished to exhort each one of you to “develop your own conversation with Christ — a conversation that is of fundamental and essential importance for a young man

2. Jesus Looking Upon Him Loved Him

In the gospel, St. Mark stresses how “Jesus looking upon him loved him” (cf. Mark 10-21). In the Lord’s look is the heart of the very special encounter and of all the Christian experience. In fact, Christianity is not primarily a morality, but an experience of Jesus Christ, who loves us personally, young and old, poor and rich; he loves us even when we turn our back to him.

“I hope you will experience such a look! I hope you will experience the truth that Jesus, keeps for you with love!” — A love, manifested on the cross in such a full and total way, that it made St. Paul write with amazement: “who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20).

The awareness that the Father has always loved us in his Son, that Christ loves every one and always, becomes a firm point of support for the whole of our human existence and enables us to overcome all trials: the discovery of our sins, suffering, and discouragement. In this love is found the source of the whole of Christian life and the fundamental reason of evangelization: If we have truly encountered Jesus, we cannot do other than witness him to those who have not yet crossed his look!

3. The Discovery of the Plan of Life

In the young man of the Gospel, we can perceive a very similar condition to yourself. You are also rich in qualities, energies, dreams, hopes: Resources that you possess in abundance! Your very age constitutes a great richness, not only for you, but also for others, for the Church and for the world. The rich young man asks Jesus: “What must I do?” The stage of life in which you are immersed is a time of discovery: of the gifts that God has lavished on you and of your responsibilities. It is also a time for you to make fundamental choices to build your plan of life. It is the moment, therefore, to ask yourself about the authentic meaning of existence and to ask yourself: “Am I satisfied with my life? Is there something lacking?”

Like the young man of the Gospel, perhaps you also live in a situation which is leading you to aspire to a life that is not just mediocre. You may be asking yourself: In what does a successful life consist? What must I do? What might be my plan of life? “What must I do, for my life to have full value and full meaning?” Do not be afraid to address these questions! Far from overwhelming you, they express great aspirations, which are present in your heart. Hence, they are to be listened to. They await answers that are not superficial, but able to satisfy your authentic expectations of life and happiness.

To discover the plan of life that could render you fully happy, listen to God, who has a plan of love for you. With trust, ask him: “Lord, as my Creator and Father, what is your plan for my life? What is your will? I want to fulfill it.” You can be sure that God will respond. Do not be afraid of his answer! “God is greater than our heart and knows everything!” (1 John 3:20).

4. Come and follow me!

Jesus invited the rich young man to go far beyond the satisfaction of his own aspirations and of his plans, saying to him: “Come and follow me!” The Christian vocation springs from a proposal of love of the Lord and can be realized only thanks to a response of love: “Jesus invites his disciples to the total gift of their life, without human calculation or benefit, with complete trust in God.

The saints accepted God’s demanding invitation, and with humble docility followed the crucified and risen Christ. Their holiness, in the logic of faith that may be humanly incomprehensible, consists in no longer putting yourself at the center, but in choosing to go against the current by living according to the Gospel. Inspired by the example of so many disciples of Christ, you also can accept with joy the invitation to follow, to live intensely and fruitfully in this world.

By your Baptism, in fact, God calls you to follow him with concrete actions, to love him above all thing, and to serve him in your neighbor. The rich young man, unfortunately, did not accept Jesus’ invitation and left saddened. He did not find the courage to detach himself from his material goods to find the greatest good proposed by Jesus. The sadness of the rich young man of the Gospel is the same sadness that enters the heart of those who do not have the courage to follow Christ, to make the right choice. However, it is never too late to respond to him! Jesus never tires of turning his look of love to you and of calling you to be his disciple.

He is proposing a more radical choice. In this Year for Priests, I would like to exhort you to be attentive to the Lord inviting you to the great gift of a religious vocation and to be available to accept with generosity and enthusiasm to undertake the necessary path of discernment.

Do not be afraid, if the Lord calls you to the religious, monastic, missionary life or one of special consecration: He is able to give profound joy to one who responds with courage!

5. Oriented to Eternal Life

“What must I do to inherit eternal life?” This question of the young man of the Gospel seems far from the concerns of many contemporary young people, because, as my predecessor observed, “are we not the generation, whose horizon is completely filled by the world and material things? But the question about “eternal life” usually comes up only ar particularly painful times, when we suffer the loss of a close person or when we have the experience of failure. But what is the “eternal life” to which the young man refers? It is illustrated by Jesus when, turning to his disciples, he affirmed: “I will see you again and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you” (John 16:22). These words point to an exalted proposal of endless happiness, of joy of being filled with divine love forever. To ask yourself about the ultimate future that awaits you will give you full meaning because it directs your plan of life toward infinite, deep, and wide horizons. That kind of questioning will lead you lead to loving the world as loved by God himself. It will lead you to liberty and joy born from faith and hope.

Searching for eternal life offers horizons that help us not to absolutize earthly realities but to see that God is preparing greater prospects for us. St. Augustine said: “We desire the heavenly homeland, we sigh for the heavenly homeland, we feel ourselves pilgrims down here”. Keeping his gaze fixed on eternal life, Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati, who died at the age of 24, said: “I want to live and not just get along!” and on the photo of an ascent sent to a friend, he wrote: “Toward on high,” alluding to Christian virtue, but also to eternal life.

I exhort you not to forget this promise of your plan of life: We are called to eternity. God has created us to be with Him, forever. This will help you to give full meaning to your choices and to give quality to your existence.

6. The Commandments, the Way of Authentic Love

Jesus reminds the rich young man of the Ten Commandments, as necessary conditions to “inherit eternal life.” They are essential points of reference to live in love, to clearly distinguish good from evil and build a solid and lasting plan of life. Jesus also asks you if you know the commandments, if you are concerned to form your conscience according to the divine law and if you will put it into practice. They certainly are questions that go against the current of the present-day mentality, which proposes a liberty disconnected from values, rules, objective norms and invites to reject every limitation to desires of the moment. But this type of proposal instead of leading to true liberty, would lead you to become a slave to yourself, of your immediate urges, of idols such as power, money, unbridled pleasure and the seductions of the world, rendering you incapable of following your original vocation to love. God gives us the commandments because he wants to educate us to true liberty, because he wants to build with us a Kingdom of love, justice and peace. To listen to them and to put them into practice does not mean to be alienated, but to find the path of authentic liberty and love, because the commandments do not limit happiness, but indicate how to find it. At the beginning of his dialogue with the rich young man, Jesus reminds him that the law given by God is good because “God is good.”

7. We Have Need of You

Today’s generation of young people find themselves facing many problems coming from unemployment, the lack of clear values and of concrete prospects for the future. At times you can have the impression of being impotent in face of the present crises and tendencies. Despite the difficulties, do not let yourselves be discouraged and do not give up your dreams! Instead, cultivate in your heart great desires of universal brotherhood, justice and peace. The future is in your hands, because the gifts and riches that the Lord has placed like a treasure in the heart of each of you, when molded by an encounter with Christ, can bring authentic hope to the world! It is faith in his love that will make you strong and generous, will give you the courage to address with serenity the journey of life and to adult responsibilities. Be committed to building your future through serious courses of personal formation and study, to serve the common good in a competent and generous way. In my encyclical letter “Caritas in Veritate” on integral human development, I listed some of today’s great challenges, which are urgent and essential for the life of this world: The use of the resources of the earth and respect for the ecology, the just division of goods and the control of financial mechanisms, solidarity with poor countries in the advancing human family issues, the struggle against hunger in the world, the promotion of the dignity of human labor, service to the culture of life, the building of peace between peoples, interreligious dialogue, the rightuse of social means of communication. These are challenges to which you are called to respond to build a more just and fraternal world. They are challenges that call for a courageous and passionate plan of life, into which you put all your richness according the plan that God has for each one of you. It is not a question of carrying out heroic or extraordinary gestures, but of putting to good use your talents and possibilities, committed to progressing in faith and love. I invite you to know the life of the saints. You will see that God guided them and that they found their way day after day, precisely in faith, in hope and in love. Christ calls each one of you to be committed with him and to assume your responsibilities to build a civilization of love. If you follow his Word, your path will also be illumined and will lead you to lofty goals, which give joy and full meaning to life. May the Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church, accompany you with her protection. I assure you of my remembrance in prayer and bless you with great affection. From the Vatican, Feb. 22, 2010

BENEDICTUS PP. XVI MARCH 15, 2010

Gospel passages

Here are some Gospel stories that ask for a Yes or a No in a climate of freedom. Re-read some of them. [Click the link under them to read noteworthy commentaries.]

Matthew 21: 28- 32 The Parable of the Two Sons

“What is your opinion? A man had two sons. He came to the first and said, ‘Son, go out and work in the vineyard today.’ He said in reply, ‘I will not,’ but afterwards he changed his mind and went.

Luke 19: 1-10 The tax collector Zacchaeus

Here is a ZENIT translation of the address Pope Francis gave today before and after praying the midday Angelus with those gathered in St. Peter’s Square. __ Before the Angelus Dear Brothers and Sisters, good morning! Today’s Gospel presents an event that happened at Jericho, when Jesus reached the city and was received by the crowd (cf. Luke 19:1-10). Zacchaeus, the head of the “publicans,” that is, of the tax collectors, lived in the city. Zacchaeus was a wealthy collaborator of the hated Roman occupiers, an exploiter of his people. He also, out of curiosity, wished to see Jesus, but his condition of public sinner did not allow him to approach the Master; moreover, he was small in stature, so he climbed up a sycamore tree, along the street where Jesus was to pass. When Jesus arrived close to that tree, He looked up and said: “Zacchaeus, come down quickly, for today I must stay at your house.” (v. 5). We can imagine Zacchaeus’ astonishment! But why did Jesus say I “must stay at your house”? What was His duty? We know that His supreme duty was to carry out the Father’s plan for humanity, which was fulfilled at Jerusalem with His condemnation to Death, Crucifixion and, on the third day, Resurrection. It is the plan of salvation of the Father’s mercy. And, in this plan, there is also the salvation of Zacchaeus, a dishonest man scorned by all and, therefore, in need of conversion. In fact, the Gospel says that, when Jesus called him, “they began to grumble, saying, ‘He has gone to stay at the house of a sinner.’ (v. 7). The people see in him a villain, who has enriched himself on the skin of his neighbor. And if Jesus had said: ‘Come down, exploiter, betrayer of the people! Come to speak with me to settle the accounts!’ No doubt the people would have applauded. Instead, they began to murmur: “Jesus goes to his house, that of a sinner, of an exploiter. Led by mercy, Jesus, in fact, sought him. And when He entered Zacchaeus’ house, He said: “Today salvation has come to this house because this man too is a descendant of Abraham. For the Son of Man has come to seek and to save what was lost” (vv. 9-10). Jesus’ gaze goes beyond sins and prejudices – and this is important! We must learn this. Jesus’ gaze goes beyond sins and prejudices; He sees a person with the eyes of God, who does not stop at past evil, but perceives the future good; Jesus is not resigned to closures but always opens, always opens new areas of life; He does not halt at appearances but looks at the heart. And here, He looked at this man’s wounded heart: wounded by the sin of greed, by the many bad things Zacchaeus had done. He looks at that wounded heart and goes there. Sometimes we seek to correct and convert a sinner by reprimanding him, reproaching him his mistakes and his unjust behavior. Jesus’ attitude with Zacchaeus shows us another way: that of showing one in error his value, that value that God continues to see despite everything, despite all his mistakes. This can cause a positive surprise, which makes the heart tender and drives the person to bring out the goodness he has in himself. It is about giving individuals confidence, which makes them grow and change. God behaves this way with all of us: He is not blocked by our sin, but overcomes it with love and makes us feel nostalgia for the good. We have all felt this nostalgia for the good after a mistake. And God Our Father, thus acts, and then Jesus acts. There is no person who does not have something good. And God looks at this to bring him out of evil. May the Virgin Mary help us to see the good there is in the persons we meet every day, so that all are encouraged to have emerge the image of God imprinted in their heart. And so we are able to rejoice over the surprises of the mercy of God! Our God, who is the God of surprises!

Discernment Process

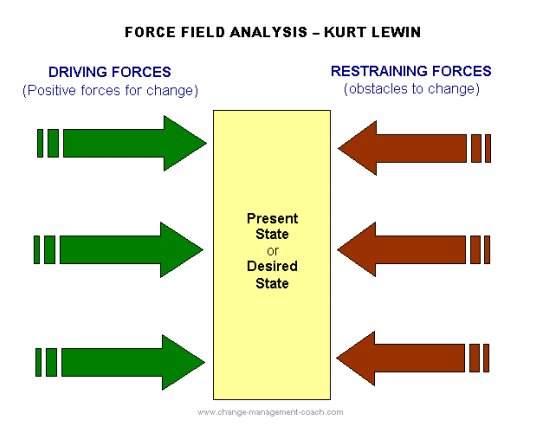

To start discernment in a thoughtful way, do a “force-field analysis” around the statement “I willingly accept to start a search to deepen in my life the spirituality of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart. ”

- Before making a decision or a change, the force field is in equilibrium between forces favorable to the decision and those resisting it. First there is a beginning equilibrium that is the status quo.

- There is tension within me about changing. For change to happen, the status quo, or beginning equilibrium must be upset – either by adding conditions favorable to the change or by reducing resisting forces.

- We name the forces on the Yes side and on the No side. Then, to show how strong each force, we give it either more weight and heft, or a number from 1 (low) to 5 (high).

- Whenever driving forces become stronger than restraining forces, our status quo or equilibrium will change.

- The naming and weighting helps us to put the decision in the full context of our life.

- There will always be driving forces that make change attractive to us, and restraining forces that work to keep things as they are.

- If we want to say Yes to the central statement, we need to strengthen the driving forces or weaken the restraining forces. Only if either or both can be done, we can honestly say Yes to embarking on developing the spiritual life of the province.

Listening and Mutual Support

We talk about what insights, desires, and discernment help you to make a decision to embark on the search for a spirituality of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart.

Footnotes

[1] Workbook 2, p. 57

[2] Oct. 4-25, 2015 Synod of Bishops

[3] cf. Homily on the Gospel of Matthew (Hom. 50, 3-4, PG 58, 508-509

[4] Andre Coindre: Writings and Documents Volume 4, Pieuse Union (Rome, 2004)

[5] AC: W&D 3, Pieux-Secours (Rome, 2002)

[6] Ibid. p. 30

[7] General Address to Pilgrims in Rome, November 19, 2014