Atlantic Ocean

Grateful Communion

Grateful Communion

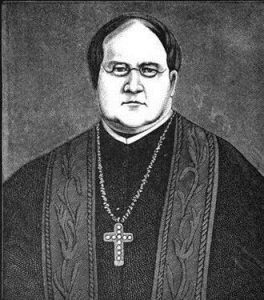

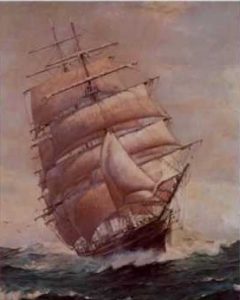

The first half of our spiritual voyage has been an extended focus on God bestowing on us gifts that feel too good to be true. God is the initiator and active protagonist of our spirituality. God’s Spirit  breathing in us is spirituality. To contemplate these profound realities, it is as though we have been, in parallel with Brother Alphonse and his companions, spending a month of nights on the deck of the Anna lying on our back pondering the starry sky of God’s blessings: our breathtaking freedom, the mercy and forgiveness that spoil us; the baptismal constellation of our divine attributes; the unearned gifts of salvation and divine empathy; the charism and genius of our founder; God’s suffering through and for him and us. The most important conviction to hold on to from the first half of our voyage is that those gifts have nothing to do with our efforts. We are cooperating passengers buoyed up in the contemplation our divine giftedness.

breathing in us is spirituality. To contemplate these profound realities, it is as though we have been, in parallel with Brother Alphonse and his companions, spending a month of nights on the deck of the Anna lying on our back pondering the starry sky of God’s blessings: our breathtaking freedom, the mercy and forgiveness that spoil us; the baptismal constellation of our divine attributes; the unearned gifts of salvation and divine empathy; the charism and genius of our founder; God’s suffering through and for him and us. The most important conviction to hold on to from the first half of our voyage is that those gifts have nothing to do with our efforts. We are cooperating passengers buoyed up in the contemplation our divine giftedness.

Gratitude for our giftedness

In the first seven lines of our map, Brother Maurice is calling us to expand the capacity of our spiritual lungs so they absorb the immensity of God’s gifts. It’s as though he’s hoping that God’s goodness will take our breath away.

Maurice is also medicating us against certain neuroses rooted in not-so-subtle heretical messages from our past: that we need to earn love and salvation; that impending judgment is a sword of Damocles over our heads; that sin is our default programing; that we, not God, are at the helm. Those messages, impressed on us by well-meaning authorities, are part of our childhood formation. We can’t un-hear them, so questions continue to churn up in us. If all is gift, why do we have religious obligations? Why so many guilt-inducing rules about prayers and sacraments? And what about that narrow gate?

The narrow gate has a bad reputation; read the story carefully.[1] Luke’s Jesus sees those who strive to enter by the narrow gate in contrast to those who expect to get into the feast because they earned a claim. The latter group had mingled in the crowds rockstarring Jesus and had listened to him teach. They had done good in the hope that God would notice and give them a ticket to the main gate. To the ticket-taker they insisted, figuring that their names would be on the VIP list, but a bouncer stepped out in front of them.

Those who teach know the difference between those minimalist students who just show up to make the grade and the rare ones who really want to engage with us to absorb what we’re offering. For Luke, those who enter through the narrow door are of the second category. They are the grateful few who want to approach Jesus with an open heart. Another “narrow door” story in Luke is the one about the ten lepers whom Jesus cleansed.[2]

Only one, a Samaritan outside the Law, came back to thank him and express personal wonder.

Only one, a Samaritan outside the Law, came back to thank him and express personal wonder.

Still another story, is the one about the striking woman, also outside the Law, who entered through the back door of Simon the Pharisee’s house[3]  so she could lavish perfume and tears on Jesus. She shows us that the “narrow gate,” the friendly back door, is for those who want to respond in fragrances of gratitude, like a neighbor who walks over to offer a freshly-baked cake in response to a favor rendered. First she feels grateful, then, as she bakes, she savors the gift given her, and finally she makes a personal visit.

so she could lavish perfume and tears on Jesus. She shows us that the “narrow gate,” the friendly back door, is for those who want to respond in fragrances of gratitude, like a neighbor who walks over to offer a freshly-baked cake in response to a favor rendered. First she feels grateful, then, as she bakes, she savors the gift given her, and finally she makes a personal visit.

The power enabling us to move beyond the first part of our spiritual voyage–recognizing God’s gifts–and on to the second–responding to them–comes from sails swollen with gusts of gratitude. Nine lepers leaned willfully into the headwind; the tenth yielded to it. Meister Eckhart, the 13th century Franciscan poet and mystic, famously said, “If the only prayer you ever say in your life is Thank you, it will be enough.”

A Communion of gratitude

Eckhart was speaking of personal prayer like that of the forgiven woman, the returning leper, and our neighbor baking her cake. In light, however, of the divine gift of communion (line 6) which binds us together in Christ, Eckhart’s quote seems too facile. A series of parallel individual thank you prayers would not be enough. Since love of God and neighbor are inseparable, our communal bond calls for a corporate thank you celebrated together. How sweet it would have been if all ten lepers had come back with their families to throw a party with cake and dancing!

At sea under the starry moonlit night, a spectacle we did not merit, we are able to fill our spiritual log book with the marvelous gifts God has offered us through the seven map stops we’ve already made, beginning with the manifesto God is Love.

We have to be careful. There is a danger in saying “God is love” and leaving it at that. Doing so could give the impression that God is a serial lover who loves each of us in a sequence of one-on-one relationships like those a gracious salesman, recruiter, or politician might cultivate. In those cases, the diverse clients who enjoy their sponsor’s attention have little or no caring contact with one another. God does not bestow love to individuals in a receiving line as at a wedding reception or a funeral. Neither does God bestow, as at the reading of a last will and testament, benevolence measured out discretely to each beloved heir. It is not even like a confessor consoling penitents one at a time.

God’s benevolence is infinitely more energizing. It gathers, it forges, it empowers new relationships, it rallies cohesion and solidarity. It is symphonic. It works a miracle of multiplication of loves. God’s explosively active way of being Love, with a capital L, has a Christian name; in Greek it is Koinonía and in Latin Communio.

Line 6 of our map uses the Latin communion twice, like the Creator kneading bread with both hands, compressing into one loaf all the gifts named in the first five lines of our map: “The grace of communion with God is also a grace of communion with our neighbor.” That one line folds together the “whole law and the prophets”[4] of our spirituality. For Maurice, the one word communion is the sum of all the divine gifts above it added up—and then multiplied. Just as the six ingredients in a bread recipe require yeast to transform them into food, Communion with a capital C is the catalyst that transforms the spiritual gifts God gives us into grace. Communion is the gravitational force of our spirituality, holding together the sea of exploding stars we contemplate from our Anna.

Our map converges with our foundational stories to give us this: God is a steadfastness of great-souled Love embracing us and moving our hearts to embrace our neighbor. God is light years of ever-expanding communion.

Most of us have felt moments of communion with God in some direct one-on-one way through the gift of prayer. Saint Margaret Mary knew the transformative power of direct mystical experience. Like her, Brother Polycarp also enjoyed a gift of fervent and consoling interior prayer. But he desired more. He hoped for something beyond personal prayer, for an experience of communion in God. He expressed his hope in a letter to the brothers in America, “Ah, if only I could introduce you to intimacy with the adorable heart of Jesus and enter with you to be burned and consumed in the intensity of divine love! I would do so happily; I think you would have reason to thank me. … Let us make a rendezvous in the divine heart.”[5] What a striking way to define communion: a rendezvous with others in the divine heart!

Heart, rather than a physical organ or even an evocative symbol, for Brother Polycarp is a spiritual feeling of affinity, a breakthrough to soulful union beyond the normal limits of space and time. Communion is the experience of being formed into a corporate heart. Sacred Heart is a reassuring and palpable force field of communion whose center is God. The breakthrough often comes through a fleeting or intuitive sense of oneness—God embedded in the many and the many in God.

One title in the traditional litany describes the Sacred Heart as “Tabernacle of the Most High” calling to mind the times when the nomadic tent in the desert was pitched anew after a stage of wandering. At those times of re-dedication, the people marveled at Moses’ face aglow in communion with God. Sacred Heart is a repeating pulse of communion. Like our pulse, we don’t usually pay attention to it, except at peak moments when it races. After the resurrection, one such moment happened on the way to Emmaus, moving two discouraged disciples to say in amazement, “Were not our hearts burning within us?”[6] Another erupted in the earthshaking roar of Pentecost, which blew God’s tent wide open to encompass a world of neighbors.

God is love. What a gift! God is communion.[7] What a more amazing gift! The Father and the Son are not twin stars rotating around each other; they are exploding stars. The explosion is the Holy Spirit. The Father and the Son live in communion with each other such that each directs us to the other. Jesus never asks us to pray to himself. Rather he directs us to pray to his Abba as “Our Father.” Likewise, the Father points us away from himself, directing us to the Son. That’s what was happening on Mount Tabor, where Peter, James, and John, in an engaging moment of communion, heard the Father’s voice: “This is my Son, my beloved. Listen to him.”[8]

Those words, which make the apostles think of pitching tents, are also addressed across the ages to us. Can we hear the motto on our coat of arms, Ametur Cor Jesu, as more than just an institutional logo? Can we hear it echo those scriptural moments of communion when the Father shouts out loud to turn us to the Son? Loved be the Heart of Jesus is the Father’s imperative for us to join him in avid simultaneous communion with Jesus and others in the ever-expanding neighborhood that is his heart.

When John F. Kennedy launched the Apollo Program, he believed it would succeed only if the American people could unite behind the lunar mission.

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. In a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon—if we make this judgment affirmatively— it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.”[9]

To accomplish the mission, the president was banking on a secular version of communion, national unity, which proved resilient enough to make the moon quest successful within the ten-year time frame he proposed.

Of our three foundational voyages, only two had similar success. Before a decade had elapsed, the brothers abandoned Dubuque. Why? A relationship of communion between the brothers and the local Church never developed. The “New Paradis” foundation began with promise. Bishop Loras had been a friend and colleague of Father Coindre during their partnership as missionaries of the Charterhouse of Lyons. Loras had also been an associate of Bishop Portier in Mobile.

Unfortunately, when the brothers arrived in Iowa in 1851 to teach elementary school and to transform 251 acres of farmland into a novitiate, Bishop Loras did not deliver on his promise of support and housing, leaving the brothers to fend for themselves. The bishop demanded services which interfered with communal life and prayer. After a short while he moved the diocesan seminary away, leaving the brothers miles to walk for any parish or chaplain. Finally, the bishop recruited two of our novices for his seminary. That was the last straw. Any promise of communion crashed. Back home in France, some brothers expressed their resentment by going so far as to agitate for the withdrawal of all the brothers from America in retaliation. Cooler heads prevailed, but in 1860 we sold the farm and left Dubuque.

Communion in our story

In contrast, Bishop Portier in Mobile drew the arriving missionaries close. With no communications from them during their voyage, he had grown anxious over unforeseen delays at sea and in port. What he thought would be a one-month crossing  inexplicably turned into more than three. With the brothers’ surprise arrival, he regained his serenity and ordered the killing of the fatted calf. One of the missionaries later described their first day in the bishop’s house. “The seasickness left us and our voyage ended as it had begun [at Paradis]. The bishop served a big luncheon with meat and all the trimmings, moistened by several good glasses of excellent wine.”[10]

inexplicably turned into more than three. With the brothers’ surprise arrival, he regained his serenity and ordered the killing of the fatted calf. One of the missionaries later described their first day in the bishop’s house. “The seasickness left us and our voyage ended as it had begun [at Paradis]. The bishop served a big luncheon with meat and all the trimmings, moistened by several good glasses of excellent wine.”[10]

They hadn’t dined so for months. On their very first day at sea, “the winds were rough and the boat extremely turbulent. When the supper hour arrived, only two passengers out of fifty showed up at table: Brother David and one Jesuit. The others were bent over the railings or were sick in their cabins.” From September to January they were in survival mode. On the last leg of the trip, while sailing the length of Cuba, “a terrible storm assaulted us. More than one of us said his act of contrition. The masts were thrown atilt to the point of slitting the tops of the furious waves then straightening up with loud cracks as though the ship was shattering and the sea, with each heave, was going to swallow us up as food.”

The missionaries continued for a while eating with the bishop in his house. Those meals of hospitality and mutual listening, along with English lessons “night and day” for three months given by the bishop and his priests, turned into a welcome grace of communion. Brothers Alphonse and David were eventually stricken by yellow fever; however, “As soon as the bishop learned of the danger, he wasted no time in sending one of the city’s best doctors to deliver them from the peril. He visited them several times a day to encourage and bless them.”

For the brothers, the gift of communion quickly expanded to include close living in a household that included seventy-five orphan boys. On a wider scale, the brothers enjoyed close relationships with the lady board members of the orphanage and its financial benefactors as well.

As the Mobile story shows, God’s gift of communion comes in the form of providential presence through human instruments. The story of the Zamzam illustrates the same truth. The distinct groups of missionaries – Protestant, sectarian, humanitarian, and Catholic – began the voyage huddled together in mutually exclusive cliques. However, once the Nazi captors forced the diverse flocks into the hold of the prison ship, their rivalries evaporated and quite an intimate communion bonded them. This unintended human communion turned out to be a positive force in the face of persecution. Later, during internment in the concentration camp, communion in faith and prayer grew deeper, enabling the diverse flock to become a force of ecumenism years before the Church officially started imagining the possibility of inter-congregational communion.

The very fact that we can pray or that we even desire to pray is part of the gift of communion. The Rule of Life calls prayer the “action of the Spirit” in us.[11] In a very real sense, it is not something we conjure up; it is a gift. The Holy Spirit, restless to fill the infinite distance between the created and the Creator, awakens prayer in us. The Spirit, present in the depths of the heart of God, draws us into the intimate life of the Trinity. God welcomes each of us, eager to be God-for-us, God-with-us, and God-among-us.[12]

Eucharist: A Process of deification

According to the Fathers of the Church and to Pope John Paul II, our prayerful experiences of communion with God and neighbor reveal that a process of “deification” or “divinization” is going on within and among us. “The Spirit makes divine all in whom [s]he breathes.”[13] Brother Maurice calls divine love “a love that divinizes human love, a love which heals and saves others, a love which engenders love.”[14] In an imperceptible but real way, prayer assimilates us into the Mystical Body (line 8). Mystical means suffused with God such that it is impossible to tell where God ends and we begin.

The reality of our being formed into one mystical body is clearest at the celebration of the Eucharist. Our historians tell us that the Anna missionaries, after two months on the Atlantic surrounded by a horizon of nothing but sky and sea, celebrated a long awaited landfall at Point-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe’s port, with Christmas Mass in the church of the hospital near the harbor.

The Rule of Life[15] says that, through the Eucharist, Jesus “draws us into his thanksgiving.” He frequently celebrated at table with his disciples in communion with outcasts and crowds. Hosting meals was a distinguishing trait of Jesus. So well-known were his public celebrations of breaking bread and sharing wine that he brought on himself charges of being a glutton and a drunkard. He didn’t deny the tag; he was intoxicated with thanksgiving.

Jesus’ image of heaven was a wedding banquet. Seemingly, he also had a

characteristic way of celebrating the Jewish ritual meal of giving thanks in a way that set him apart from other rabbis of his time. After the resurrection, the disciples of Emmaus didn’t recognize him by his exterior appearance. Their “aha moment” didn’t come until he led the prayers of the breaking of the bread and the sharing of the cup in his customary unique way.

For Jesus, communion was best expressed at a meal. For this reason, article 116 of the Rule of Life holds our celebration together of the Eucharist as our primary response to the love shown through the Sacred Heart event. The Jesus version of the Jewish beraka is simultaneously a gift of communion and a thanksgiving memorial continuing the Sacred Heart event of the outpouring of water and blood that began the cross. That article echoes the faith Andre Coindre had that the Eucharist is the first thing we do in the response phase of our spirituality: “The sacrifice of the Mass embodies the most perfect tribute of adoration, thanksgiving, and prayer that we can offer to God in honor of his divine majesty and in seeking help in all our needs.”[16]

Eucharist, lived as a free response over time, is our lifelong act of thanksgiving for the phenomenal gifts of God listed in our map. It is also our celebration of ongoing communion, keeping alive the special table fellowship that gave Jesus so much joy.

Enhancing Eucharistic communion

We can enhance our participation in Eucharistic communion by finding ways to make it more intentional. One way is to watch our language. We talk about receiving or taking communion. We say things like “I went to communion.” or “Did you receive holy communion?” In our common parlance, the host is communion. Those expressions make communion into an object. That is a flat caricature. Communion is something well beyond an object; it is a ritual and a celebration of the uplifting experience of God’s presence at the heart of our human existence.

Just as we confirm aloud our faith in the real presence of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine by a vocal Amen, can we find ways to express intentional and interactive acts of faith in the other ways the Lord is really present? At each Mass we attend, how can we show that we believe the Lord is present in each of the baptized who are present? Can we purposefully and spontaneously animate the human joy of communion through warm interaction with one another? Can we listen to the Word being proclaimed and to the celebrant throwing himself into the celebration in the place of Jesus?

A second way to enhance our Eucharistic communion is by purifying our motive for going to Mass. How much of our motivation is obligation? …the human respect of being seen? …giving good example? …anxiety about pleasing God? …a desire to build stronger communion? …to seek reconciliation? …to encounter the risen Jesus? …to express sincere thanksgiving? …to join in the full-throated singing of the Church?

A motive for celebrating Eucharist particular to us with our spirituality is to go to mass to memorialize and relive the Sacred Heart event as it is etched in article 114 of the Rule of Life.

The Open Heart

The Gospel reveals the pierced side of the Savior

as the source of the life-giving Spirit,

the channel and symbol of divine love.

From his open side

out of which blood and water flow,

Jesus gives birth

to the Church and the sacraments.

He invites all to his heart

“to draw water with joy

the springs of salvation.” (Is 12:3)

At Mass, we can take our place with the two beloved disciples at the foot of the cross, joining in their gesture of love and presence to the man beloved to them. With them we contemplate the crucifix and the wounds. We concentrate on the cost he paid and on arousing in our heart empathy with his suffering. With John and Magdalen, we remain faithful to being there even though the others have dropped out. We revere the moment of the pouring of the water and wine and join in consecrating them as springs of salvation. We partake of the cup, and, with the sign of the cross, we renew our baptismal consecration and our commitment to being his real presence and his hope.

8

Atlantic Ocean

Grateful Communion

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

The Grace I Seek …

Father, send me your spirit of gratitude so that I will recognize your love in everything you have given me. And you have given me everything. Every breath I draw is a gift of your love, every moment of existence is a grace, for it brings with it immense graces from you. Lord Jesus, give me love for the great communal celebration of gratitude around your word and altar that is the living Church. Holy Spirit, fill me with enthusiasm and joy in being one with the communion of vocations, educators, students and alumni that draws its spiritual vision and its mission from the charism you poured out on Father Andre Coindre.

Hymn of Communion—Animés de l’Amour

We listen and meditate on the lyrics of the traditional hymn of gratitude for the experience of communion. [To open: Hold CTRL then click on link. Click again. To return to lyrics: SHIFT back arrow.]

https://video-e1.myschoolcdn.com/354/3003903/3/video.mp4

| Antienne Animés de l’Amour dont on s’aime entre frères, qu’il est bon, qu’il est doux d’habiter un seul lieu, qu’il est bon, qu’il est doux, au sein de nos misères, de n’avoir qu’un seul cœur pour bénir un seul Dieu. Verset Être unis par l’Amour, quel sort plus désirable? Que l’âme goute en paix ce plein contentement. Le monde n’en a point qui lui soit comparable. Restons unis toujours comme en ce doux moment. (2) Verset (RISE) Dans l’amour du Sacré-Coeur nous sommes vos partenaires; Notre mission est de fournir aux élèves un sanctuaire. Unis, nous donnons vie à la vision du Père Coindre. Restons unis toujours comme en ce doux moment. (2) |

Refrain Charged and alive with Love that binds us close, how good it is and pleasant to be together in one place! How good it is and pleasant, in the midst of our woes, to be of one heart praising our one God. Verse To be bonded in Love, what more could we desire? Let our hearts take delight in the feel of such happiness. The world offers nothing that can compare to it. Let us stay forever one in this blessed communion. (2) Verse (RISE) As partners in the love of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, our mission’s to provide sanctuary for our students. Together we give life to the vision of Père Coindre. May we always be as one as in this moment blest. (2) |

Pray Psalms of Thanksgiving

[Those with keyboard devices, open music clip first, then SHIFT/Psalm link]

Psalm 8 http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/8

Psalm 139 http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/139

Psalm 147 http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/147

Music to accompany praying the Psalms: Contemplating the Stars by LOUIS-ALBERT BOURGAULT-DUCOUDRAY

Pray hymns from the Liturgy

Te Deum (Canticle of Feast Days)

Easter chant Exsultet – Rejoice

Hymn of Communion: Surely, the presence of the Lord is in this place, Composed by Lanny Wolfe Sung by the Brother Martin High School Chorale, New Orleans, LA

Refrain:

Surely the presence of the Lord is in this place.

I can feel His mighty power and His grace.

I can hear the brush of angels’ wings.

I see glory on each face.

Surely the presence of the Lord is in this place.

There’s a holy hush around us as God’s glory fills this place.

I’ve touched the hem of His garment, I can almost see His face.

And my heart is overflowing with the fullness of His joy.

I know without a doubt that I’ve been with the Lord.

Communion from a Psychologist’s Point of View

In his book, The Art of Loving, Erich Fromm declares that our most basic need is not, as Freud maintained, to satisfy the demands of our libido, but rather to escape the prison of our aloneness and find union with other human beings. He then goes on to discuss three ways in which people try to achieve this goal: 1) the orgiastic state of sexual union, 2) conformism, and 3) creative or productive activity. These three attempts to achieve communion, however, are much less satisfactory than that of love. As Fromm expresses it: “The unity achieved in productive work is not interpersonal; the unity achieved in orgasm is transitory; the unity achieved by conformity is only pseudo-unity. Hence they are only partial answers to the problem of existence. The full answer lies in the achievement of interpersonal union with another person, in love.”

Fromm feels, however, that love has been widely misunderstood, so he examines what he considers its true nature. He says that love is a state which permits both individuals to retain their freedom. He adds that love is primarily giving, rather than receiving. But it is not the giving of material things, nor is it giving in the sense of sacrificing or of being deprived of something. It is, instead, an expression of empowering and giving of life by the giver. By giving some of what is alive in him or her — joy and sorrow, interest and understanding, the lover shows freedom to give. In addition to the characteristic of giving, Fromm says that love has four other basic elements: care, responsibility, respect and knowledge.

“Respect” means the concern that the other person should grow and unfold as he or she is… If I love another person, I feel one with the beloved. But not just that. I feel one with the person as he or she is, not as I need him to be, not as an object for my use.” (p. 28).

“Knowledge” according to Fromm is what most helps us to penetrate to the core of the beloved. But this is not necessarily rational knowledge. Love is active immersion in the other person, my desire to know the person is stilled by union. In the fact of union, I simultaneously know you and I know myself, I know everybody and I know nothing. The only way to have full knowledge of another lies in the act of love: this act transcends thought, it transcends words. It is the daring plunge into the experience of union (pp. 30-31). According to Fromm, then, union is not something we know, but rather something which we can only experience through the act of giving ourselves in love.

After having examined the active elements of love, Fromm observes that there are several different types of love, two of which – love of neighbor and erotic love – are important in our spirituality. Love of neighbor is important, not only because of its relation to other types of love, but because of its function in producing communion. According to Fromm: “The most fundamental kind of love, which underlies all types of love, is love of neighbor. Love of neighbor is love for all human beings; it is characterized by its very lack of exclusiveness. If I have developed the capacity for love, then I cannot help loving others. In love of neighbor there is the experience of union with all persons, of human solidarity, of human “at-onement.” Love of neighbor is based on the knowledge that we all are one (p. 47).

In his discussion of erotic love, Fromm says that sexual contact by itself is not enough to produce union: “If the desire for physical union is not stimulated by love, if erotic love is not also love of neighbor, it never leads to union in more than an orgiastic, fleeting sense. Sexual attraction creates, for a moment, an experience of union, yet without love this union leaves strangers as far apart as they were before. Sometimes it makes them ashamed of each other, or it even makes them hate each other, because after the illusion has gone they feel their estrangement even more markedly than before.” (pp. 54-55). If erotic love includes love of neighbor, however, it may also be a means of achieving communion. According to Fromm, “Erotic love, if it is love, has one premise. That I love from the essence of my being and experience the other person within the essence of my being. In our essence all human beings are identical. We are all part of The One; we are One.” (p. 55)

In a later work, The Revolution of Hope, Fromm explains further his theory that we all are One. In a discussion of empathy and compassion he declares that those who feel these emotions can achieve union because, in their most basic nature, all human persons are identical: “The essence of compassion is that one suffers with or feels with another person. This means that the lover does not look at the other person from the outside, thus making that person into the “object” of interest or concern. It means that that one person puts her- or himself into the other person.

Compassion (or empathy) implies that I experience within myself what is experienced by the other person and I sense that through this experience the other and I are one. Fromm believes that each of us has within ourselves the basic characteristics of all other persons, so that what we experience is essentially the same as what is experienced by the other person.

Armand F. Baker, State University of New York (Albany) published at http://www.armandfbaker.com/publications.html

Eucharist: Memorial and Thanksgiving

Hymn: Memorial Ndolo Ike

Come to the feast

All you wounded and weak

Come and receive the bread of life, the bread of life

Come to the feast

From the greatest to the least

Drink and believe the blood of life, the blood of life

And the memory of who I was

Fades away in the arms of love

Watch my fears come undone like a thief on the run

from the unrelenting heart of God (2)

Come to the table

All you broken and unabled

We’re beggars to be made whole again, made whole again

And come to the table

Empty handed and grateful

Taste and see the goodness of the Lamb the great I am

And the memory of who I was

Fades away in the arms of love

Watch my fears come undone like a thief on the run

From the unrelenting heart of God From the unrelenting heart of God (Bridge)

We’re all dry bones longing for a savior

waiting for the God of life to put us back together

We’re all dry bones longing for a savior

waiting for the God of life to put us back together

We’re all dry bones longing for a savior

waiting for the God of life to put us back together

And the memory of who I was

Fades away in the arms of love

Watch my fears come undone like a thief on the run

from the unrelenting heart of God

from the unrelenting heart of God.

Gospel Eucharistic Contemplation

The Last Supper John ch.13

I place myself in the scene as one of the characters and keep my attention focused on Jesus.

Last Supper JC Superstar

Last Supper Passion of the Christ

Jesus of Nazareth Zefferelli

Eucharist as Thanksgiving Donna Kelly, cnd

The word Eucharist comes from the Greek εύχαριστία meaning thanksgiving. It is the name given to the central act of Christian worship. This title can be explained both by the fact that at its institution Christ gave thanks. “Then he took the cup, and after giving thanks … then he took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it.”[17] The service of thanksgiving after the manner of Jesus is the supreme act of Christian thanksgiving.

In the celebration of the Eucharist we come together to offer praise and thanks to God primarily for the Paschal Mystery—Christ’s dying and rising for humankind and our incorporation into that mystery through Baptism. We also give thanks for all that God has done and continues to do for us personally and as members of the Body of Christ. In the Eucharist we celebrate the story of Jesus of Nazareth, including his earthly ministry and his death, the story of Jesus as Lord, with God from the beginning. It is not only a celebration of Jesus in the past, but of Jesus who speaks God’s living word into our lives now, leading us in Eucharist — profound thanksgiving!–for all we have received; it is also a celebration of our own personal story.

We do not offer our thanks and worship to God directly, but rather through Christ who is our Redeemer and Lord. The celebrant is Jesus Christ who, through his Spirit, is present in the Church. Christ enables us to praise, thank, remember and celebrate our story. Christ does not celebrate alone however; Christ and those baptized into Christ comprise the celebrating community. Jesus Christ offers praise and thanks on our behalf and in our words and actions of praise and thanks. A spirit of thanksgiving and gratitude fills our hearts as we gather with the Christian Community to enter into this great prayer of thanksgiving. Given the kind of society we live in today, is a grateful heart something that we naturally bring to Eucharist or must we work to develop it?

Diligent parents begin very early to teach their children to say the magic words: “Please” and “Thank you.” As we grow up and leave the confines of the family those lessons of our parents should go with us. But has an attitude of thanksgiving become part of the fiber of our being? Are the words “thank you” part of our daily vocabulary or have we allowed it to become a relic of the past? Our culture and society often teach us an attitude which goes against gratitude. Our culture says “you deserve to receive gifts” or “you earned what you have.” Children get the impression from society that parents are expected to do things for them: to look after their needs even into adult life; to give them expensive presents when they succeed in school; and to pay them when they perform household chores. Married couples at times have expectations of one another which prevents them from seeing the other person’s actions as gift: cooking a meal, cleaning house, doing laundry, earning a living, watching the children and numerous other activities. Are our homes places where children see modeled a spirit of gratitude so that the attitude found in our society is challenged by what they live at home?

Besides the story of the ten lepers, there are numerous passages throughout the Scriptures in which the words thank, thanks, thankful, thankfulness, thanking, thanksgiving, etc. are prominent. It is impossible to cite them all; however, this spirit is central in Hebrew and Christian stories, prayers and texts. In our prayer life we become engrossed in asking God for favors and forget that at Eucharist we are called to “give thanks and praise.” There are times when we get caught up in our activities and responsibilities and we forget to take time to turn to God and say a very simple “thank you” for the gifts we receive every day. The celebration of Eucharist is an opportunity to focus on this aspect of our relationship with God. A grateful person is one who can see a gift and say: “this is a gift, someone gave me something I did not deserve.” God has given us many gifts: the gift of creation, life, health, family, etc. God gave us the gift of Jesus, the Son, who in turn gave us the ultimate gift, the gift of his life freely offered for us. In the words of John (15:13): “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.”

This gift of his life out of love has been given to us as a gift we cannot earn. Are we striving in our personal lives to see the gifts that God gives us, so that we can reply with ‘thank you’? Do we respond with a ‘thank you’ to the gifts and kindnesses that other people give us? Let me illustrate from a personal experience. As a senior in university, I was preparing for my recital. I was a clarinet major and therefore was expected to give a recital in fulfillment of one of the requirements for a bachelor’s degree. Much of the music written for the clarinet has piano accompaniment.

The accompanist I had recruited for my recital was a beautiful young woman one year younger than myself; Laura Hefley was her name. Because the music I was playing for my recital was challenging for the pianist as well as for myself, Laura was required to practice long hours and we were required to spend hours practicing together to get ready. We had even performed one of the pieces for a special recital given by the music sorority to which we both belonged. After each rehearsal with Laura I always told her how much I appreciated the amount of work she was putting into the preparation of the music. I always finished the rehearsals with numerous expressions of ‘thank you’ to her.

In February of that year Laura was raped and murdered on our college campus. It happened during the winter break when there were few students around. Laura had stayed on campus to work on her piano music — both for me and for her own music school performance requirements. So often, after the death of a loved one, people are heard to say: ‘I wish I had told Jane how much I cared, or how much I appreciated things she did for me.’ As difficult as Laura’s death was for me and for all the students in the music school, I did not have to carry into the future a regret for not having expressed to Laura my appreciation for all her work.

The simple phrase ‘thank you’ offered to someone we love expresses the appreciation which we feel in our hearts for the goodness and kindness of the actions of others. A number of spiritual writers have written about the quality of a grateful heart. Ronald Rolheiser in Holy Longing says: “Sanctity has to do with gratitude. To be a saint is to be fueled by gratitude, nothing more and nothing less.” He continues: “In the Gospels, the call to have a mellow, grateful heart is just as nonnegotiable as are the demands to keep the commandments and practice social justice.”

Passage from Part I to Part II

Tacking Westward: from Thanksgiving to Response

“Sailing ships can’t make 90° turns,” explains a skipper experienced in sailing three-masted barques of the tall ship class of the Anna. “The best angle a square-rigger can make towards the eye of the wind is about 60°. That equates to sailing two miles to make progress of one mile. Tacking on a barque requires time, skilled manpower and considerable effort from all hands. A single tack can take close to half an hour, or more, with all hands hard at work. And for much of that time bedlam reigns.

“Orders bellowed out are relayed from station to station. Crew members add their shouts, goading each other to greater effort. Whipped by the wind, sails crack like gunshots; pulley blocks rattle annoyingly against masts and yards; the ship creaks and groans. Often howling wind, heavy rain and darkness add to the apparent disorder.

“The command ‘Tack ship!’ is shouted and the helm is pushed against the wind. Then the main sails near the stern are hauled around to help the rudder force the stern around, keeping the momentum going. With sails slack, the ship’s bow is pushed steadily to position itself in the wind. On deck, crews haul the main yardarm around to fill its sail and maintain forward motion. They pull up the triangular jibs to catch the wind. They trim the yards and sheets, and the barque slowly gathers way on her new tack.”[18]

After considering the immensity of God’s gifts during the first part of our journey, we are poised for the second part, which corresponds to all the human efforts of the crew on the Anna to partner with the wind. In this second movement we deploy our gratitude in an active response to God’s prevailing initiatives. In the first part of our voyage, God was the protagonist. In the second, we strive[19] with all urgency to respond.

As we start talking about our own good works, whether prayers and masses or gestures of almsgiving, charity, and service, whether individually or in community, we have to avoid the trap of regressing to that aberrant spirituality which calculates and hoards good works in an effort to appease God or merit favorable treatment. We’ve got to resist any thought of using good works as a key or combination to pick the lock of God’s treasure box. That approach is a temptation we must resist. Our response has to be as free as God’s initiatives.

Nevertheless, ours is an active spirituality, so works–including hard work–are important. Brother Borgia, the leader of the first generation of Brothers, wrote to Father Coindre in 1825 complaining of all he had to do and expressing a yearning for a more contemplative lifestyle. The founder’s answer included this:

Nevertheless, ours is an active spirituality, so works–including hard work–are important. Brother Borgia, the leader of the first generation of Brothers, wrote to Father Coindre in 1825 complaining of all he had to do and expressing a yearning for a more contemplative lifestyle. The founder’s answer included this:

“My dear and beloved brother, imagine the King of France learning with pleasure news of his armies fighting in Spain. Would he not prefer to see them there, in spite of their exhaustion, rather than to see them idly singing his praises at his court? Well then, our God needs soldiers who can endure the weariness of the day-to-day even more than he needs contemplatives who only honor him with their lips! Sword in hand, zeal for his glory, a desire to save, to teach, to edify one’s neighbor, this is what our God loves above all. ‘Those who teach others will shine as stars for all eternity,’ says the prophet.”[20]

Our founder imagines God calling us to move from contemplation to action – from the “sweetness and calm of prayer” to the “weariness of the day-to-day.” Our zeal to teach, save, and educate grows from our contemplation of the gifts that have been poured over us.

At this point in our voyage, our heart is like a steamer trunk which God has filled with all the spiritual, human and deifying graces that Brother Maurice has laid out for us.

Remember the controversy over the precious coffer of seeds from the farm at Paradis destined for Dubuque. Someone in Paradis had wanted to hoard the seeds much as Borgia wanted to hoard his prayer time for himself. However, Brother Polycarp entrusted Brother Ambrose with the seeds as a free gift so he could, by dint of hard work, grow food for the orphans. As in the parable of the talents,[21] God, who wants us to invest in others the riches with which the Spirit has deified us, “pours out his love that must flow through us to others.” (Line 7b) Taking our cue from God and Ambrose, we put no lock on the treasure chest God has filled to overflowing for us. Our good works are a free act of response to our giftedness. We open to others the gifts with which God has entrusted us.

Footnotes:

[1] Luke 13 : 22-30 https://www.sacredspace.ie/scripture/luke-1322-30

[2] Luke 17: 11-16

[3] Luke 7:36-50

[4] Matthew 22:4, Galatians 5:14

[5] Workbook 2 (1981) p. 92

[6] Luke 24:32

[7] Theological Commission for the Great Jubilee of 2000, The Holy Spirit, pp. 15 and 17. The commission uses the words communion and trinity interchangeably.

[8] Mark 9:7

[9] Delivered in person before a joint session of Congress May 25, 1961

[10] Annuaire 2: 111-113

[11] Article 130

[12] Theological Commission, p. 22.

[13] Athanasius, Letter to Serapion I, 14

[14] We are Present to them …, par. 60

[15] Article 136

[16] Notes de Prédication, manuscript 111

[17] Luke 22:17, 19

[18] cf. http://www.oceannavigator.com/Ocean-Voyaging-Blog/ January 1, 2003

[19] The verb strive in the NT is a strong and concrete one, used to describe muscle strain, as in the drive of a runner to win a race.

[20] AC:D&W 1: Letters, Letter VII, p. 84

[21] Matthew 25:14–30