Jerusalem

The Beloved Disciples

The Beloved Disciples

John and Magdalen

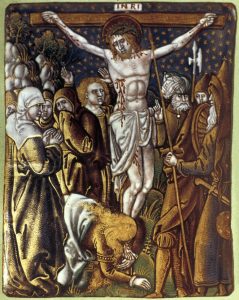

At the start of Brother Maurice’s letter on the response phase of our spirituality, his first contemplation opens a window on the scene of the soldier piercing the side of Jesus. He asks us to join him in training our gaze on those at the foot of the cross.

Brother Maurice contemplates John, the disciple whom Jesus loved,[1] who had been with Jesus at some of his most intimate moments, seeing him cry over the death of his friend Lazarus and, at the last supper, resting his head on Jesus’ chest as they reclined at table.

We watch the beloved disciple interact with someone else beloved to Jesus, Mary of Magdala. We know less of her than we do of him. We do know that she had been a disciple of Jesus from the beginning of his ministry.[2] For centuries, Western Christianity depicted her as a former prostitute, a narrative that conflated her with the anonymous sinful woman mentioned in the Gospel of Luke. Since 1969 the Church has held that she was distinct from the sinful woman. Modern scholars believe she was a woman of high social status and wealth who accompanied and travelled with Jesus, helping him and the other disciples with her own resources. Pope Francis recently put her feast on a par with the liturgical celebrations of the male apostles.[3]

In the scene, we also see who is not there: no Peter, no James, no Twelve. John and Magdalen are the only ones from Jesus’ band with the courage to enter the narrow door of close presence at his most vulnerable and shameful moment. To do so, they had to empty themselves of fear, doubt, and human respect. We see their resolve. They stand for “all men and women” (map line 8) who deliberately accept a vocation to draw close enough to Jesus to “follow the lance with their eyes.”[4]

The Sacred Heart Event

As eyewitness to that historical event, John deliberately set out to proclaim that what he had witnessed really happened.[5] He wanted his absent contemporaries and us his followers to know he wasn’t making it up:

“This is what we proclaim to you: what was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked upon and our hands have touched. … We have seen and bear witness to it, and we proclaim to you the eternal life that became visible to us. … so that you may share life with us.”[6]

Those words opening the 1st letter of John, are those of an eyewitness testifying to other disciples that the piercing of Jesus’ side and the flow of water and blood were a historical event of divine grace. The two beloved disciples wanted the Sacred Heart event to be part of the proclamation made by the succession of Jesus’ disciples.

Our institute can claim to be a direct descendant of John’s proclamation of the Sacred Heart event. Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna, a contemporary of the beloved disciple, personally knew the Beloved Disciple and his community in nearby Ephesus. He had often heard John preach, and he upheld the historicity of John’s story. Polycarp in turn passed it on to his student, Irenaeus, who brought it to Lyons where he was named bishop. In that role, at about forty years of age, he quoted John’s proclamation in a letter he wrote before the year 200.[7] Irenaeus then testified to John’s eyewitness in Lyons, where we find it in the preaching notes of Andre Coindre.[8]

Our contemplation of the two disciples standing at the foot of the cross and following the lance with their eyes leads us to the same conclusion as Brother Maurice, namely that it is not enough to watch the piercing or let our hearts be moved to empathy and prayer. There is another step: to proclaim to others our faith in the eternal life it revealed to John and Magdalen and to later generations.

Being close to Jesus and wrapped by prayerful contemplation in the mystery of his loving self-emptying is the aspiration of a devotee. If there is anything crystal clear in the writing of Brother Maurice, it is that being a devotee is not enough. Our response must include becoming a disciple of the Sacred Heart.

Responding as Disciples of the Sacred Heart

What does it mean to respond as a disciple?

Colin Harris of Mercer College, in his column in an online Baptist publication, uses football to make an important distinction between a devotee and a disciple. Football fans are passionate about their team, buy the logo shirts and season tickets, and watch all the game footage, but even the diehard ones never think of working out with the team, learning how to run the plays that entertain them, or even taking up the sport. Fans’ relationship with the team that is the object of their devotion might last a lifetime, but it doesn’t involve changing their life. There are analogous Christian devotees who show their devotion by wearing the jewelry, saying the prayers, making the retreats and devotions, and even publicly avowing their adherence, but not making the sacrificial option to live their lives with, like, and for Jesus Christ and his saving mission.

To make the spiritual journey with Brother Maurice requires disciples, not mere devotees. Disciples are like apprentices in relationship to their mentor artisans in crafts and trades. The choice to be a disciple involves a rigorous process of disciplined growth in imitation and in perpetuation of the master’s life work. Each stage of growth is a step to the next level. The master commissions disciples to complete the work he or she has started; the master trusts the disciple to remain inspired by the ideals and the original beauty he or she has introduced into the world.

At the premiere of the opera Turandot at La Scala in Milan in 1926, two years after the great Puccini’s death, the conductor Arturo Toscanini stopped the performance at the end of the third act, put down his baton, turned to the audience and said bluntly: “Here is where we finish the opera. At this point the master died.” By his blunt gesture, the conductor wanted to honor the great composer, of whom he was a fierce devotee. Not heard were the final two scenes, written by Franco Alfano, whose orchestration the dying master himself had directly commissioned him to complete, along lines suggested by Puccini himself. After fifty-six years of Turandot’s being performed around the world using Toscanini’s truncated ending, an opera scholar unearthed and produced the original ending written by Alfano, whom Puccini had chosen as his disciple. Opera critics raved, “this original is lusher, more grandly laid out, and altogether more satisfying.”[9]

Toscanini was a devotee; Alfano was a disciple whose contribution still lives after generations of performances. Our apostolic work as disciples was commissioned by the Master, who wants us to trust ourselves and our gifts. As disciples, if we can stay connected to Jesus at the heart, we can be faithful to his inspiration and effective in prolonging his noble mission.

To point us to true disciples who can be our model, Maurice has taken us to the foot of the cross. The others whom Jesus had called had lost their inspiration. Like Toscanini, they said, “This is where the master died.” There, beside Jesus’ mother, stood those who made the option to be disciples to the last: John and Mary of Magdala. They accepted the task of putting on his mantle and taking up his mission.

As we continue on our spiritual voyage, we need to place ourselves there with them. We ask them to pray with us for the grace to be disciples like them. They witnessed his final act of love, his words of pain and promise, and the piercing of his heart. Praying for and cultivating an identity of disciple in the manner of the two beloved disciples is the core of Brother Maurice’s vision for a spirituality of the Sacred Heart. In his words, we pray to be given “the heart of a disciple,” which grows from an “experience of deep friendship with Jesus.”[10] “Because our heart is purified and transformed by frequent encounters with the Lord, we develop our desire to become disciples” who keep Jesus’ mission alive beyond his death. Jesus never promoted himself; he promoted salvation for the lost. True disciples, unlike devotees, never lose sight of the eternal plan for that mission.[11]

In his circular letter, Brother Maurice portrays our spirituality as “discipleship of the Heart,” calling us to express our spirituality not only in devotional times of prayer, but also, and perhaps more importantly, in the heat of active service in our mission. If we can make our own the prayer of Brother Maurice, we can understand how spirituality motivates discipleship.

Jesus’ last words to his Beloved Disciples

As Puccini on his deathbed entrusted Alfano to complete his opus, Jesus used his last breath to confide the continuance of his mission of love, healing, and salvation to the two disciples (map line 7). In John’s Gospel, he spoke three last words. We contemplate those words[12] as imperatives addressed to us for the discipleship phase of our spirituality.

Behold your mother.

I thirst.

Now it is finished.

Contemplate your mother.

Jesus tells us: The lance has pierced her heart too. I heard her gasp when she saw the cross. I felt her anguish when she gave up waiting for the twelve to mount a rescue plan. I groaned that she had no choice but to watch. Admire her and the women and learn from them. Lean on their strength. Listen to them. Advocate for them. Who else loves me as they do? Don’t be a just a son to her; be a brother, a sister, an adult who respects her as an adult. Make your heart her home. Make her heart your hope.

I thirst…

… for tears from you. But not for me. Shed them instead for the women, their terrified children and those untimely stifled. I thirst for the presence of the twelve who drank from the cup with me. My mouth is too dry to speak or even to moan. My tongue is stuck. I thirst for you to speak for me. To be my voice. To pray with me. To forgive for me. I thirst for justice to rain down, for hope withered for want of watering. I need someone to carry water for me and for those as helpless as I am.

… for tears from you. But not for me. Shed them instead for the women, their terrified children and those untimely stifled. I thirst for the presence of the twelve who drank from the cup with me. My mouth is too dry to speak or even to moan. My tongue is stuck. I thirst for you to speak for me. To be my voice. To pray with me. To forgive for me. I thirst for justice to rain down, for hope withered for want of watering. I need someone to carry water for me and for those as helpless as I am.

I am finished …

… poured out, spent. Wrap yourself in my mantle of gentleness and humility. I have planted, it is for you to harvest the hundredfold. I’ve uttered the last word, it is yours to make it reverberate. I am empty; now you pour yourself out. Salvation has come, you have to prove that it’s real and here. I am reduced to a force of one, you must increase and multiply sanctuaries to gather those around whom I want to wrap my arms.

At the tomb

After Nicodemus lays Jesus in the tomb and while the other disciples remain paralyzed by fear, we continue our contemplation of the two beloved disciples.[13] As they were at the cross, they are the first responders at the grave, where the risen Jesus is awaiting Mary with tender patience. In the pre-dawn she wakes up with one thing on her mind: to find his battered body and console it with balm. Seeing the tomb open and empty unhinges her. Stolen! Desecrated! When she hears “Mary” pronounced in the tone of voice she knows so well, she falls to her knees and throws her arms around Jesus’ legs.

After that, it’s all running and elation. She rushes to find the others: “I have seen the Lord.” John, running headlong before everyone, is the first man to reach the tomb and the first among the men to believe what Mary was shouting: not stolen, risen! He sees the linens still shaped in the contours of the body. Grave robbers don’t leave the wrappings behind. He is risen!

What does our contemplation of the two disciples at the cross and the empty tomb tell us about how to respond?

First, we identify ourselves as descendants of John and Magdalen, as beloved disciples who constantly keep before our eyes as our reference point the pierced heart flowing with the love of God. Then we become an intentional source from which that same living water flows.

Forgive

That living water is forgiveness. John and Mary heard the risen Jesus commission them to forgive others in his name.[14] They pardoned the other disciples who fled, who disowned Jesus, who hid, who doubted, who betrayed, who regressed into the mode of every-man-for-himself.” Forgiveness is a saving event that works two ways: We drink in the consolation of being forgiven ourselves, and we forgive others in the name of Jesus.

According to the Church’s daily prayer, the knowledge of our salvation comes from the forgiveness of our sins.”[15] We don’t know we’ve been saved until we experience forgiveness. Nothing spreads the living water of salvation to young people more effectively than forgiveness. We correct them, we have them make amends, we form their sense of right, and then we forgive them. Those steps are saving acts – living waters. The experience of forgiveness is the beginning of young people’s awareness of God’s salvation. They need us for that awareness. The Lord needs us to give them that awareness.

Proclaim the resurrection

As beloved disciples, we also respond in a second way; we broadcast the glimpse of eternal life that John and Mary witnessed while following the lance with their eyes. We proclaim their good news. As we’ve seen, our distinctive cross is one way to proclaim the centrality of the Sacred Heart event for us. That cross does capture his self-emptying on Golgotha, but our contemplation of Mary and John goes beyond the events on Golgotha; it also includes the scene during which Mary recognizes Jesus risen from the tomb.

An essential part of our response is proclaiming our faith in the resurrection, which shows that the world has felt an influx of the risen Christ. Like the beloved disciples, we believe that because Jesus was raised from the dead, he has the spiritual power to transform us according to his image. We believe that the risen Jesus replaces Adam, involving us and the whole of humanity in his destiny of newness.[16]

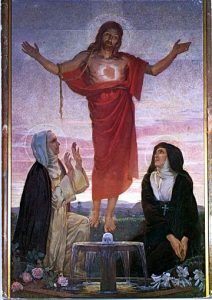

Since it is not our vocation to be preachers or ministers of the sacraments, one way we can proclaim the resurrection to the young is through images. We can present images of the Sacred Heart to the young as post-resurrection appearances of Jesus. Through sacred art, the risen Lord can appear to them displaying the forgiveness, divine love, and human affection that burn for them with mystical fire in his heart. Through them he can invite the young, as he did Thomas, to touch the wounds in his hands and side.

Images of the Resurrection

In 17th century France, John Eudes[17] imagined the power of such images. He promoted the first versions of an icon of Jesus, his arms raised

in blessing and his pierced heart exposed on his chest. Margaret Mary knew that image, as did a mystic in the Eudist tradition, Sister Mary of the Divine Heart. We have all seen variations of such an image in the form of the statues, pictures and, banners that gained wide currency in French spirituality and later throughout the world. They have inspired artists and sculptors of many cultures. They are ever-present on our campuses. One is on the cover of Brother Maurice’s circular.

Some of us find the traditional image off-putting, preferring to interpret the heart as an interior mystery of grace that is better not caricatured. Its stylized realism seems to some like an oversimplification. Before relegating it to the archives of pious devotion, though, it might be helpful to look at it the way John Eudes did.

He too believed that the true mystery of the heart is interior. However, not being a contemplative mystic but an active missionary, he was a realist. What he sees in the image he offered are two hearts, one exterior and one interior.

“In the interior heart is a permanent disposition of availability, but it is always expressing itself through active external gestures in real time and in changing ways. The inner heart generates outer initiatives of love to express its inexhaustible riches. Thus, the loving disciple can, at one and the same time, dwell within this expansive double Heart, rooting himself in a lasting home – a state of being – while forging outward to invent ways of living the inner mystery through outgoing public action – a state of doing.”[18]

John Eudes’ icon of Jesus is an undeniable proclamation of the resurrection. Besides showing public witness, the outer heart adds to the image of the risen Lord a reminder of the events of his passion, his wounds, and his death as well as of the central proclamation of God’s saving love revealed in the Sacred Heart event.

Jerusalem

Beloved Disciple and Mary of Magdala

Prayer, Reflection, Exchange

The grace I seek …

John and Mary, I’d like to think I’d have stayed here with you in the chaos of the cross, but the tale of my response to life’s storms begins with the word “evacuate.” Pray for me. Pray dearly for me to be able to make my own the shock and shame that has taken your breath away. Gather me close and hold me here trembling with you on this Friday we call “Good” until I can settle down and fix my gaze on his side pouring out goodness that I find too good to be true. Keep repeating for me the words that are reverberating in your hearts, totally attuned to his agony and his hope. Ask him to make me a convinced and convincing disciple like you are, you who can’t take your eyes off him.

Join the Prayer in the heart of Mary Magdalen

Guided Contemplation from the Doctors of the Church

Contemplation By a medical doctor

Contemplation The Crucifixion

While listening to Ennio Moricone’s music from “The Mission,” contemplate Tintoretto’s Crucifixion scene, the largest and most elaborate painted by the masters. [Click music clip arrow above. Diminish clip. Maximize ‘Map of our Heart’ page. While holding Shift key, Click on image link below. Use + to enlarge the image; use slide bar to explore details of image.] [To end: pause video clip. Proceed by scrolling ‘Map of our Heart.’]

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacopo_Tintoretto_021.jpg#/media/File:Jacopo_Tintoretto_021.jpg

Psalms of Jesus during his passion

The Psalms were Jesus’ prayer book. He knew most of them by heart. To contemplate the most intimate prayers of his heart, we listen to the psalms and pray them aloud to share in his prayer.

The “I” in these psalms is Jesus, extended to the suffering and marginalized people whose plight he took into his heart and with whom he identified. His prayer expressed their prayer. Before praying these psalms we pray for the grace to experience compassion for him in his time of crisis and empathy with the feelings of those whose passion he bore.

Those with devices with a keyboard may play a musical background while reading: a string quartet playing Haydn’s “The Last Seven Words of Jesus Christ.”[Click music clip arrow. While holding Shift key, Click on link to a psalm. Pray the psalm. Afterwards, close it using X tab, then click to another.] [To end: pause video clip. Proceed by scrolling down.]

Liturgy of the Hours

Monday of Holy Week

Psalm 31 Mon Wk II Readings http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/31

Psalm 42 Mon Wk II Morning Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/42

Tuesday of Holy Week

Psalm 37 Tues Wk II Readings http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/37

Psalm 43 Tues Wk II Morning http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/43

Psalm 119: 49-56 https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm+119%3A49-56&version=NIV

Psalm 54 Tues Wk II Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/54

Wednesday of Holy Week (Spy Wednesday)

Psalm 55 Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/55

Psalm 62 Evening Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/62

Holy Thursday

Psalm 56 Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/56

Psalm 57 Thurs Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/57

Psalm 72 (pt II) Thurs Wk II Evening Prayer

Good Friday

Psalm 2 Office of Readings http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/2

Psalm 22 Office of Readings http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/22

Psalm 38 Office of Readings http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/38

Psalm 51 Morning Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/51

Habakkuk’s Canticle

http://www.liturgies.net/Prayers/canticles.htm#habakkuk

Psalm 40 Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/40

Psalm 54 Morning Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/54

Psalm 88 Morning Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/88

Psalm 116: 10-19 Evening Prayer

https://www.biblestudytools.com/nlt/psalms/passage/?q=psalm+116:10-19

Psalm 143 Evening Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/143

Holy Saturday

Psalm 64 Morning Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/64

Canticle Isaiah 38 Morning http://www.liturgies.net/Prayers/canticles.htm#hezekiah

Psalm 27 Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/27

Psalm 30 Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/30

Sunday of the Resurrection

Psalm 118 Daytime Prayer http://www.usccb.org/bible/psalms/118

Pope Francis and the Church contemplate Mary of Magdala

https://aleteia.org/2016/06/10/mary-magdalene-apostle-to-the-apostles-given-equal-dignity-in-feast/ (Scroll down after reaching the Aleteia site)

Rule of Life 114 The Open Heart

Prayer: Convert the article into a personal prayer expressing your faith, hope, and love.

The Gospel reveals the pierced side of the Savior

as the source of the life-giving Spirit,

the channel and symbol of divine love.

From his open side

out of which blood and water flow,

Jesus gives birth to the Church and the sacraments.

He invites all to his heart

“to draw water with joy

from the springs of salvation.” (Is 12:3)

The Sorrowful Mother

Read an excerpt from The Testament of Mary. (Colm Toibin (Scribner 2012)

I gasped when I saw the cross. They had it ready, waiting for him. It was too heavy to be carried and so they made him drag it to the crowd. I noticed how he tried to remove the thorns from around his head. A number of times, but the efforts did not succeed, and seemed instead to make them further push themselves into the skin and into the bone of his skull, and his forehead. Each time he lifted his hands to see if he could ease the pain of this, some men behind him grew impatient and they came with clubs and whips to pressing forward. For a time he seemed to forget all pain and he pushed across forward or pulled it. We moved quickly ahead of him.

It was when I caught his eye that things changed. We had moved ahead, and suddenly I turned I saw that once again he was trying to remove the thorns cutting into his forehead. Failing to do anything to help himself, he lifted his head for a moment and his eyes caught mine. All of the worry, all the shock seemed to focus on a point in my chest. I cried out and made to run towards him, but was held back by my companions. They whispered to me that I would have to be quiet and controlled, or I would be recognized and taken away.

He was the boy I had given birth to and he was more defenseless now than he had been then. And in those days after he was born, when I held him and watched him, my thoughts included the thought that I would have someone now to watch over me when I was dying, to look after my body when I had died. In those days, if I had even dreamed that I would see him bloody and the crowd around him filled with zeal that he should be bloodied more, I would have cried out as I cried out that day and the cry would have come from a part of me that is the core of me. The rest of me is merely flesh and blood and bone.

They told me that I must not attempt to speak to him, that I must not cry out again. I followed them towards the hill.

We waited and it took an hour or maybe more for the procession to arrive. It became easy somehow, to tell the difference between those who were there for a reason, who were in the pay of somebody, acting on instructions, and those who were merely there as spectators. What was strange was how little attention some of them paid as others set about nailing him to the cross and, then, using ropes, trying to pull the cross towards the hole they had dug and balance it there.

Each of the nails was longer than my hand. Five or six of the men had to hold him and stretch his arm along the cross and then, as they started to drive the first nail into him, at the point where the wrist meets the hand, he howled with pain and resisted them as blood spurted out and the hammering began as they sought to get the long spike of the nail into the wood, crushing his hand and his arm against the cross as he writhed and roared out. When it was done, he did everything to stop them stretching out his other arm. One of them held his shoulder and one the upper arm, but still he managed to hold his arm in against his chest, so they had to call for help. And then they held him and drove in a second nail so that his two arms were outstretched on the wood.

I tried to see his face as he screamed in pain, but it was so contorted in agony and covered in blood that I saw no one I recognized. It was the voice I recognized, the sounds he made that belonged only to him. I stood and looked around. There were other things going on—horses being shoed and fed, games being played, insults and jokes being hurled, and fires lit to cook food, with the smoke rising and blowing all around the hill. It seems hard to fathom now that I stayed there and watched this, that I did not run towards him, or call out to him. But I did not. I watched in horror, but I did not move or make a sound.

We held each other and stood back. That is what we did. We held each other and stood back as he howled out words that I could not catch. And maybe I should have moved towards him then, no matter what the consequences would have been.

I asked how long it would take for him to die, and was told that because of the nails and the amount of blood he seemed to have lost, and the heat of the sun, then it could be quick, but it could still take a day unless they came and broke his legs, and then it would be quicker. There was a man in charge, I was told, and he knew how to make time go faster or slow it down. He was an expert. That is what he did, in the same way as others were experts in crops and seasons, the time to harvest the fruit from the trees, or the time it took a child to come into the world. They could make sure, I was told, that no more blood would be spilled, or they could even turn the cross away from the sun, or they could use spears to pierce his flesh, and this would mean that he would die within hours, before nightfall.

I was suddenly afraid. It was my own safety I thought of, it was to protect myself. It is only now that I can admit this. But I must say it, I must let the words out—despite the panic, despite my desperation, my shrieking, despite the fact that his heart and his flesh had come from my heart and my flesh, despite the pain I felt, the pain that has never lifted and will go with me to the grave, despite all of this, the pain was his and not mine.

Prayer to Mary

Listen to a musical version of the Stabat Mater for background as you pray the English translation below.

Interpret it as prayer not only to Jesus’ mother at Calvary, but also to the Father, who feels feminine empathy and experiences disabling grief in communion with Mary.

English translation by Beatrice E. Bullman (edited)

Mother bowed with grief appalling

must you watch, with tears slow falling,

on the cross your dying son!

Through my heart, thus sorrow riven,

must that cruel sword be driven,

as foretold – O Holy One!

Oh, how mournful and oppressed

was that Mother ever-blessed,

Mother of the Spotless One:

She, whose grieving was perceiving,

contemplating, unabating,

all the anguish of her Son!

Is there someone, tears withholding,

Christ’s dear Mother thus beholding,

not partaking in her woe?

Who that would not grief be feeling

for that Holy Mother kneeling?

What suffering was ever so?

For the sins of every nation

she beheld his tribulation,

giv’n to scourgers for a prey:

Saw her Jesus foully taken,

languishing, by all forsaken,

when his spirit passed away.

Love’s sweet fountain, Mother tender,

haste my hard heart, soft to render,

make me sharer in your pain.

Fire me now with zeal so glowing,

love so rich to Jesus, flowing,

that I favor may obtain.

Holy Mother, I implore You,

crucify my heart before You,

guilty is it verily!

Hate, misprision, scorn, derision,

thirst assailing, failing vision,

railing, ailing, deal to me.

In Your keeping, watching, weeping,

by the cross may I, unsleeping

live in sorrow for his sake.

Close to Jesus, with You kneeling,

all your dolors with You feeling,

O grant me this, the prayer I make.

Maid immaculate, excelling,

peerless one, in heav’n high dwelling,

make me truly mourn with You.

Make me, sighing, hear Him dying,

ever newly vivifying

all the pains that pierc’d him through.

With the same scar lacerated,

by the cross enfired, elated,

wrought by love to ecstasy!

Thus inspired and affected

let me, Virgin, be protected

when sounds forth the call for me!

May his sacred cross defend me,

He who died there to befriend me,

that His pardon might suffice.

When my earthly frame is riven,

grant that to my soul be given

all the joys of Paradise!

The Teaching Jesus: our image of the Risen Lord

A memorable part of the animation of Brother Jean-Charles Daigneault, former superior General, was his exposition of the “Teaching Jesus,” a bronze statue in the foyer of CIAC which was commissioned by the 1898 alumni class of Saint Louis College. They wanted to offer the Brothers a work of art to express the image they had of their mentors. The statue stands as an icon of Father Coindre’s personal charism, in imitation of Jesus, transformed into the charism of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart.

“Christ is walking: look at the flow of his garments and notice the position of the feet. … He is walking energetically. He leans forward in a dynamic way. There is an imperative force that is calling him forth. There is little time to fulfill his mission. There is an urgency to evangelize the people. He has only three years to do this.

“Christ is walking: look at the flow of his garments and notice the position of the feet. … He is walking energetically. He leans forward in a dynamic way. There is an imperative force that is calling him forth. There is little time to fulfill his mission. There is an urgency to evangelize the people. He has only three years to do this.

He strides forward

–with lively step; there is little time

–without sandals

unconcerned about the condition of the road ahead

–the hot sand

–the hard rocks

–the damp earth

in order to better experience the human condition.

His garments flow as he moves forward

moving forward with vigor

slowing down only to address the needs of others…

His arms are open wide and extended

greeting without discrimination…

those who do not know where to go.

His open mouth utters simple words

–a warm greeting

–easy to understand

–words mysterious at times,

for they speak of the mystery of his grace

(one day to be ours)

but he does not speak as priests would

–he speaks with the authority

of the Father whose message he communicates

–he elicits confidence

–he pardons faults

–he encourages

–he invites to conversion

–he shares in our life.

His eyes look

–with tenderness on those who wish to know him

–with sadness on those who are without a shepherd

–with compassion on those who have nothing,

–who have been hurt by life

–with mercy on those who sinned.

His eyes scan the road before him;

sees the traps that are ahead,

the cross that is the will of his Father,

my cross and the crosses of all men and women.

His heart beats

generously for one and for all – none are forgotten

at times too fast, rapidly at times

beats always for others

in harmony with the heart of his Father.

Christ the Teacher

walks along the road

under the hot sun and the driving rain

against the high winds of a storm

and the gentle breezes, the whisper of the Spirit.

His mission knows no bounds

he is a man dedicated to others addressing urgent needs.”

It is finished: An Easter Homily

http://bemidjicovenant.com/filerequest/3773.pdf

Footnotes

[1] Scholars of John’s Gospel and letters are not sure whether John the Evangelist, John the Apostle, and the beloved disciple are one or more persons. Here we follow Brother Maurice’s usage. Scholars are more certain that the beloved disciple who witnessed the crucifixion is the same as the author of the first letter of John. In his circular, Brother Maurice does not make mention of Mary of Magdala, most likely because he was presenting a male model for the brothers. Scholars have no doubt that Magdalene was at the side of the beloved disciple, that she was a leader among the disciples of Jesus, and that the risen Jesus appeared first to her.

[2] Luke 8: 1-2

[3] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/mary-magdalene-feminism-metoo-jesus-disciples-apostle-christianity-judaism-pope-francis-vatican-a8281731.html

[4] We are Present to Them, par. 2; John 19: 34-35 cf. Rule of Life 114 (2007)

[5] John 19:35 is the only place in the New Testament where the writer steps out of character to aver that an event being reported is a historical fact.

[6] 1 John 1: 1-2

[7] William A. Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, vol. 1 (Collegeville MN, 1970, p. 107)

[8] Notes de Prédication, pp. 234-236, Manuscript 23

[9] NY Times November 5, 1982

[10] We are Present to Them, 7

[11] Ibid, 8

[12] John 19: 26-30

[13] John 20:1-18

[14] John 20:23

[15] Canticle of Zachary, Luke 1: 77

[16] Theological Commission, Jesus Christ, Word of the Father, 1997, p. 99

[17] Born 1672

[18] http://www.eudistes.

L’intérieur est la face de la disponibilité permanente, s’exprimant à l’extérieur comme accomplissement effectif du mystère, dans un ensemble toujours nouveau de gestes actifs qui créent hic et nunc l’événement d’amour en ses composantes inépuisables… En logeant sa vie dans ce double grand Cœur, le chrétien peut donc s’enraciner dans une demeure stable, être en « état » de… et il peut, en cela même, marcher toujours, en continuant d’inventer sa participation active au mystère.

[19] Colm Tóibín, The Testament of Mary (Scribner, 2012) excerpts from pp. 56-65